Explaining Behavior 14: Pure Sociology

The geometry of law, partisanship, lynching, and science

This is part of a series on how to explain human behavior. It is based on a course developed by the late Donald Black at the University of Virginia. Parts 1 through 6 discussed the general logic of scientific theory. From Part 7 onward we cover different strategies or paradigms for developing explanations. The last installment was Part 13: NeoDarwinian Theory.

In the 1960s, American cities had a bad habit of erupting in flames every summer. The main cause of these rebellious ghetto riots was some altercation between black citizens and the police. One result was the Johnson Administration supporting a spate of research in which trained observers rode around in police cars to observe how cops interact with citizens. The cops did not know this was the aim of the study, thinking instead the observers were there to study criminals.

Sociology graduate student Donald Black took a leading role in designing this research, and also did his own stint riding in patrol cars in Detroit. You can find the results of the research in his book The Manners and Customs of the Police. But the descriptive material wasn’t the most important thing to come out of his time in the field.

Black witnessed great variation in how police responded from one case to another, even if the legal substance of the case — say, one person allegedly struck another in the face — was the same. Sometimes cops intervened forcefully and arrested the accused; sometimes they intervened in a conciliatory way and tried to make peace between the disputants; sometimes they made only the briefest appearance and drove off without doing anything at all. Black struggled for some general principles that would explain this variation.

His quest took him beyond policing in America. He studied other parts of the legal system, such as trials, sentencing, and litigation in civil courts. He began to read widely in the history and anthropology of law, studying the legal systems of diverse societies like ancient Babylonia, the Nuer of the Sudan, and the Zapotec of Mexico.

Eventually, he had an epiphany: As a sociologist of law, he wasn’t trying to explain the behavior of police, or judges, or jurors, or crime victims. The proper subject matter of his field was the behavior of law itself.

Law, he realized, was a quantifiable force like gravity or electromagnetism. It is defined by the amount of governmental authority brought to bear against an alleged deviant. Law increases when mobilized by citizens to handle their disputes: A call to the police was a small increment of law, an increase of government authority in the conflict. It remains a small amount of law even if the police never arrive — but if they do, this is a further increase in the quantity of law. If the police arrest the alleged deviant, that is more law still. And so on throughout the legal process: Law ceases to increase if the charges are dropped but continues to increase if they proceed. A more serious charge, carrying a bigger potential punishment, is a greater increase of law than a lighter charge. A conviction is more law than an acquittal. A severe sentence is more law than a lenient one.

And one can similarly quantify civil litigation: A call to an attorney, the filing of a suit, a decision for the plaintiff, a larger damage settlement — all are increments of the quantity of law.

As a quantitative variable, law increases and decreases from one situation to another, from one legal case to another, from one alleged crime or dispute to another. And if you can explain the quantity of law, you can explain when crime victims will call the police, and when the police will arrest, and when prosecutors will bring charges, and when judges and juries will convict.

Much like other natural forces, it varied with its immediate environment. The force of gravity between objects varies with their distance, as does the force of electromagnetism. And, Black proposed, so does law. But whereas gravity and electromagnetism decrease with physical distance, the force of law increases with a kind of social distance — what he called relational distance. The more closely related the parties in a legal case — the more involved in one another’s lives, the longer the history of their relationship, the greater their time spent together — the less law the case attracts. The more distantly connected, the greater the quantity of law.

The plays out at every phase of the legal process. It influences which injuries people define as crimes in the first place, and their likelihood of invoking law in their conflicts. People are least likely to call the police if they are victimized by intimates such as close kin and domestic partners. The same offense by a mere acquaintance is more likely to result in a call to the police, and law is still more likely if the offender is a total stranger.

If the police are called, they are less likely to get involved if the parties are intimates. Officers are more prone to drag their feet on the way to “domestic” calls, to knock softly and hope no one hears. They are more likely to dismiss the dispute as mere family trouble and leave no official record that a crime occurred. The more distant the disputants, the more likely they are to define the matter as a crime and to arrest the alleged offender.

Among cases that do produce an arrest, those involving intimates are most likely to result in dropped charges. Among cases where charges are brought, distant cases attract more severe charges and are more likely to proceed to a guilty plea or a guilty verdict in court. And in cases that result in a guilty plea or conviction, the more distant the relationship between offender and victim, the more severe the sentence is likely to be. Hold constant the nature of the crime, and the length of the prison sentence varies directly with relational distance. So too does the probability of the death penalty.

All these patterns are implications of a single general principle: Within a society, law varies directly with relational distance.1 This, Black claims, is a “sociological law of law” that holds not just in modern America, but in legal systems around the world and throughout history. It even explains the evolution of legal systems: They are largely absent in the highly intimate world of hunter-gatherer bands and simple tribes, and only emerge historically with the growth of large-scale societies in which people live in proximity to distant acquaintances and strangers.

Black first introduced this relational distance principle in his book The Behavior of Law. Here he also advances several other propositions to explain legal variation. For instance, he proposes that law varies directly with social status, meaning that cases between people of high status (such as the rich and respectable) attract more law than cases between people of lower status.2 The principle downward law is greater than upward law implies that cases where a low status person is accused of an offense against a higher status person result in more law than in cases where the low accuse the high. There are also principles describing the impact of culture, division of labor, and the availability of competing systems of dispute settlement, as well as some addressing the style of law — such as whether the deviant is defined as a criminal to be punished or a disordered person in need of treatment.

Whatever value Black’s theory of law might have for explaining legal outcomes, it also stands as an example of a distinctive strategy of explanation. Some refer to this paradigm with the eponym Blackian theory. Black himself preferred to call it pure sociology.

Pure Sociology

Pure sociology differs from the other sociological paradigms in this series in that it represents a self-conscious attempt to create a new sociological paradigm. As this series shows, Black put a lot of thought into analyzing and classifying approaches to sociology. He also sought to make a new approach that combined some aspects of existing paradigms while eschewing others.

One thing he eschewed was psychology. Here Black was spurred on by sociologist George Homans who, in his book Nature of Social Science, argued that every sociological explanation worthy of the name was at core psychological — that is, based on some proposition about what people think, feel, want, or want. The idea that sociology and social psychology were different disciplines was a myth: All sociology was social psychology.

Black took this as a challenge. He set out to create a purely sociological theory that explained behavior without claims or assumptions about human subjectivity. Hence his proposition, law varies directly with relational distance, says nothing about what anyone involved thinks or feels about the case, whether they like or want more law or less law, or what rationale they use when making legal decisions. It’s plausible that crime victims, police officers, prosecutors, judges, and jurors all have different interpretations of and reasons for their actions. But it matters not: In Black’s paradigm, all that matters is that their behavior obeys the same sociological principle.

Not only does Black’s theory lack psychological propositions, but it also lacks any teleological explanation. It doesn’t assert that law or legal outcomes serve any particular purpose, function, goal, or interest. It says nothing about whether society or some segment of society has the amount of law it needs, whether law is functional or dysfunctional, whether law seeks to uphold a certain social class.

In my installments on functionalism and conflict theory, I mentioned some of the weaknesses of collective teleology, and it is not that unusual for sociologists to acknowledge the problem with attributing goals to entire societies. But Black goes further and argues that all teleological explanation is unscientific. In his article “The Epistemology of Pure Sociology,” he observes that ancient and medieval scholars had teleological explanations of the physical world, but that these fell by the wayside as physical science grew more scientific. He argues his own paradigm’s abandonment of teleology is a similar advance.

Teleology hampers testability, he argues, for the ends of people are no more directly observable than the ends of societies, the ends of falling objects, or the ends of God. And since attributing good or bad motives is an aspect of how we judge or justify behavior, teleological explanations confuse the distinction between empirical description and value judgment.

Pure sociology, Black argues, does not even focus on individual people as such. Individual actions are only relevant as indicators of the behavior of some form of social life, such as law, altruism, predation, or science. The core unit of analysis in pure sociology is neither the person nor society, but the instance of behavior: The legal case, the conflict, the homicide. The actors might be individual people, or organizations like armies or corporations or states.

The dependent variables of pure sociology are aspects of social life, such as its form, quantity, and style. The independent variables are a social structure defined by the relationships of all the actors involved in each instance of social life. And it is here that Black’s paradigm tries to synthesize other approaches. Classical theorist Emile Durkheim paid great attention to patterns of social integration and division of labor, but little to social stratification. Karl Marx explained all of social life with inequality of wealth but gave no explanatory value to intimacy or culture or interdependence. Black’s paradigm recognizes these and other variables as part of a multidimensional social space.

Social Structure and Social Space

Pure sociology explains behavior with its social structure. In sociology, social structure usually refers to some patterning of the society as a whole, such as whether it is divided into a class of nobles and a class of commoners. But in pure sociology it refers to the structure of the behavior itself, or perhaps of the situation or relationship that gives rise to it — the structure of the conflict, of the lawsuit, of the lynching.

Blackian theory describes this structure in terms of a social space. Black defined five dimensions of social space. Though he initially singled out one dimension — wealth — as the dimension of social stratification, he recognized that other dimensions also gave rise to a kind of social status and social inequality. Thus over time he increasingly lumped several together as being vertical aspects of social life, each a subdimension of social stratification.

Wealth, his original vertical dimension, refers to the material means of existence, such as food, shelter, tools, and whatever currencies can be exchanged for them. The rich have a higher social elevation than the poor, and a complaint by a poor person against a rich person is an upward complaint.

Social integration arises from participation in social life — being at the center of a community, highly involved in activities and relationships with others. While it might be thought of a horizontal position, in Black’s theory of law it behaves like a social status, such that an outward complaint by an integrated person toward a social marginal is effectively a downward complaint.

The same goes for two kinds of cultural status. One is the quantity of culture, such as the amount of lore and language a person is fluent in. This is the form of status that brings respect to knowledge specialists and, in many human societies, to elders in general. The other is the conventionality of culture, a form of stature that places majorities above minorities, and that makes having weird beliefs, dress, or customs socially debilitating.

Organization is the capacity for collective action. A group is more organized than a lone individual. A bigger group, all else equal, is more organized than a smaller one, and a group with a division of labor and leadership is more organized than one without these. Many human societies have had little inequality along this dimension, as virtually all members belonged to some sort of corporate kin group and few if any larger organizations existed. Modern societies are far more stratified in this regard, with atomized individuals finding themselves in interactions with massive bureaucratic states and megacorporations.

Finally, the moral aspect of social life, praising the virtuous and punishing the deviant, defines its own dimension of status. Black referred to it as normative status or respectability, and others might call it as prestige or reputation. Those with criminal records or other history of deviance have lower standing on this dimension, those who command respect stand higher.

Black and other pure sociologists sometimes mention additional subdimensions of social status, such as functional status (skill at a task) or authority (rank in chain of command).

Social elevation is one’s degree of status, either on any one dimension or, quite often, a composite of all of them. Vertical distance is the amount of status inequality between two people are groups. Vertical direction is defined by who acts toward whom: A lawsuit by a wealthy corporation against a poor individual is downward law, the assassination of a high-ranking official by a poor minority is upward violence.

But despite sociologists often having a preoccupation with it, the vertical dimension of social life — even defined broadly to include a half dozen subdimensions — is not the whole of the social world. Horizontal dimensions include the aforementioned relational distance — a degree of participation in one another’s existence, measurable by such indicators as the length of relationship, time spent together, range of shared activities, and mutual connections in a social network. Organizational distance refers to shared group membership, or lack thereof — a concept of importance in Mark Cooney’s work on feuding and gang warfare. Functional interdependence is how much two parties cooperate for survival and well-being. Cultural distance refers to differences in cultural traits, such as dress, language, and religion.

All of these are sometimes lumped together as kinds of social distance that tend to have similar effects on behavior.

These do not exhaust the variables used in pure sociology. My discussion doesn’t even touch on the dynamic aspect of social space — fluctuations in relational distance or vertical distance. But it’s enough to help the reader understand some further examples of Blackian explanation.

These kinds of social distance and social status define the social structure of a behavior, and the assumption of pure sociology is that behavior varies with its structure — that certain forms and quantities are more likely across short distances or long ones, in upward directions or downward ones, at higher elevations or lower ones.

Because of the spatial language, Black and other pure sociologists sometimes refer to the social geometry of behavior and describe the paradigm as explaining behavior with its social geometry.

The Behavior of Conflict

Most pure sociological theory deals with the various ways that people handle disputes and respond to deviance. In his Social Structure of Right and Wrong, Black defines conflict as “a clash of right and wrong” in which someone “provokes or expresses a grievance.”3 It exists whenever anyone treats another person or their conduct as deviant, whether they react to that deviance as a crime, sin, negligence, symptom of disorder, personal betrayal, or mere rudeness.

Black’s early work focused on law as form of conflict management — the use of state authority to handle a grievance. But he observed that law in this sense was one of the rarest ways of handling conflict. Most grievances do not result in so much as a call to the police or threat of litigation. Other responses range from the fleeting and mild (harsh glares, temporary sullenness) to violent retribution that, in state societies, is itself defined as a crime.

Black classified five “elementary forms” of conflict management: Self-help (the use of aggression, as in “taking the law into one’s own hands”), avoidance (curtailing contact with the offender), negotiation (verbal compromise), settlement (bringing the case before a neutral third party), and toleration (inaction, as in “turning the other cheek”).

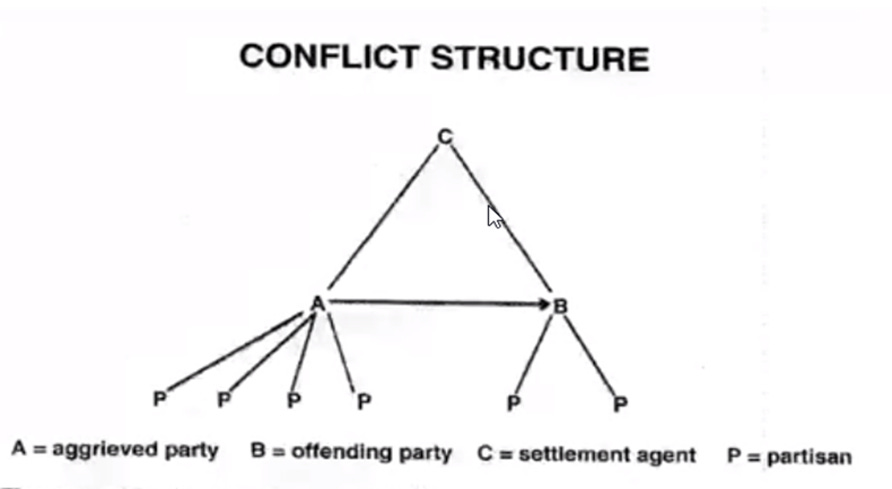

Black (along with M.P. Baumgartner) also distinguished some different roles parties might take in a conflict, most fundamentally the distinction between the principals — the aggrieved and the alleged offender, be they individuals or groups — and third parties — anyone else exposed to the dispute. The social geometry of the conflict includes the social distances and statuses of all these parties.

One of Black’s elementary forms is settlement by a third party, such as judge. The key feature is that the settlement agent is significantly neutral — even if they ultimately side with one disputant or the other, there is some chance for both sides to present their case. Such neutrality is more likely when the third party is not much relationally or culturally closer to one side or the other. This is his principle of isosceles triangulation: Settlement is most likely when three parties form an isosceles triangle of social distance, with the potential settlement agent at its apex.

Another feature of settlement is that the disputants submit to the input of a third party in the handling of their conflict. Perhaps the third party has the authority to compel them to abide by the settlement, or perhaps merely merits enough respect for others to seek his opinion. Either way, settlement is more likely if the third party is a social superior rather than an equal or inferior: “Settlement behavior is more likely to occur when the third party is higher than the principals in social status.”

Thus the settlement agent is the apex of a triangle of social elevation as well as social distance, leading Black to dub the social structure of settlement a triangular hierarchy.

Settlement agents vary in their degree of authoritativeness, as measured by the extent to which their intervention is decisive, rule-oriented, coercive, and punitive.

The least authoritative act as friendly peacemakers, simply trying to restore harmony without any coercion, punishment, or explicit judgment or right and wrong. Mediators are somewhat more rule-oriented, acknowledging the right and wrong of the matter, but they render no final verdict and inflict no punishment. Arbitrators are still more rule-oriented and decisive — they do render a verdict, but have little ability to coerce the parties into accepting it. Judges can coerce the parties into accepting their verdict and are more likely to proscribe punishment for the party in the wrong. The most authoritative judges dole out punishments quite liberally: “In Manchu China, judges punished someone in nearly every case: the accused if found guilty, otherwise the ‘unjustified accuser.’” Still more extreme, repressive peacemakers might punish both sides just for the temerity of having an open conflict.

The authoritativeness of settlement is a direct function of the social distance and status superiority of the settlement agent. Authoritativeness increases with the height and area of the settlement triangle.

Thus:

The frequency and severity of punishment by third parties increases with social inequality and the breakdown of intimacy . . . Almost unknown in egalitarian tribes, it comes when strangers invade everyday life and resources concentrate. And it comes with the state . . . Punishment had its golden age in ancient empires such as those of Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Rome . . . Penalties included the amputation of hands, feet, and testicles, binding, branding, burying alive, crucifying, impaling, slicing, flaying, boiling, pouring hot oil into the ears or mouth, and exposing to wild beasts or vicious dogs . . . .

If isosceles triangulation produces neutrality, then being substantially closer to one side than another produces its opposite: Partisanship. Partisanship, taking sides in a conflict, is a matter of degree: Some third parties express a mild preference for one side, others immediately judge one side wholly in the right and the other wholly in the wrong, and might offer varying degrees of support in the conflict, up to and including violently attacking the wrongdoer on behalf of the aggrieved.

Black proposes that partisanship obeys a principle of social gravitation, in which closeness and social superiority attract partisans to a disputant. Thus: Partisanship is a joint function of the closeness and superiority of one side, and the remoteness and inferiority of the other.

The principle explains when who principals try to recruit as partisans and who successful they will be, as well as which third parties will offer which degrees of support to one side or the other. It also explains different patterns of support, neutrality, and conflict.

Consider the effect of distance. The strongest partisans are extremely close to one side and extremely distant from the other.

These are prone to act swiftly and severely, expressing certainty about who in the right and who is in the wrong, and perhaps attacking and killing the enemy.

Strong partisanship not only arises from social polarization—every third party close to one adversary and distant from the other—but also produces moral polarization. Each side commonly regards itself as totally right and the other as totally wrong. Compromise is difficult. Conflict is likely to be protracted, prone to escalation, and possibly violent. Illustrations include feuding, rioting, and warfare.

Maintain closeness to one side, but increase closeness to the other, and partisanship weakens and warms:

When third parties are socially close to both adversaries (though closer to one, as in figure 7.2), they are likely to show concern (“warmth”) for both, even if ultimately, they take sides. The pattern of conflict may be ambivalent and unstable. If physically close, the participants often become agitated, noisy, and even violent, as illustrated by the melees that sometimes erupt among hunters and gatherers such as the !Kung Bushmen or Walbiri Aborigines. Third parties pulled in opposite directions may also display indecisiveness or lack of commitment. Conflict tends to be dissipative, losing its momentum almost as soon as it begins. For example, fights among the !Kung usually end within seconds or minutes, everyone laughing at their own behavior…Right and wrong lose their clarity and importance.

Make the third party equally close to both sides, they tend to be friendly peacemakers, taking neither side but expressing concern for both. Make them quite distant from both, they become “cold” nonpartisans, expressing indifference. If other conditions are right, they might settle the conflict; otherwise, they are prone to leave the disputants to themselves.

Varieties of Blackian Explanation

Some Blackian theories, like the theories of authoritativeness and of partisanship, focus on one variable feature of conflict. They explain why conflict management is more or less authoritative, more or less violent, more or less therapeutic, and so forth.

Others try to explain some particular form or pattern of conflict management, like why a grievance gets handled with a distinct pattern of violence like lynching, rioting, or terrorism.

One strategy for doing this is to propose a series of relationships between the likelihood of that form and various dimensions of social space. This is what Black did in his theory of law, proposing that it increased with relational distance, and increased with elevation, and was greater in downward directions.

Historian and sociologist Roberta Senechal de la Roche takes a similar approach to lynching in her articles “Collective Violence as Social Control” and “The Sociogenesis of Lynching.” She defines lynching as violent self-help meted out with individual liability by a group with low organization: A temporary and informally organized mob targets particular individuals who are accused of wrongdoing. This definition distinguishes the pure lynch mob from related patterns, like rioting (similarly disorganized but employing collective liability) and organized vigilantism by groups like the Regulators, Slickers, or Ku Klux Klan.

Having distinguished a particular way of handling conflict, she proposes a series of relationships between lynching and the vertical, relational, functional, and cultural dimensions of social space. For instance:

As with law, an upward offense—by a social inferior against a social superior—is treated more seriously and results in more punitiveness than a downward offense by a social superior. When an offense is upward, the direction of the complaint or grievance is downward. Accordingly: Downward lynching is greater than upward lynching. And the vertical distance is important as well. As the degree of inequality between the parties in such downward cases increases, so does the severity of the violence inflicted.

Her proposition explains, for instance, why the most common scenario for lynching in the Jim Crow South was when a black person was accused of victimizing a white person. It also explains why whites lynched for victimizing other whites tended to be of unusually low status, having “problems with drugs or alcohol, a history of previous criminal behavior, vagrancy, or vagabondage.” And it explains why the risk of lynching was greater when a black killed an especially high-status white person, such as an employer or lawman. White mobs were less likely avenge the socially down and out, even in crimes that crossed the color line.

She also proposes that “lynching varies directly with cultural distance.” For example:

“In late nineteenth-century Georgia, Alabama, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, for example, proselytizing by Mormon missionaries was sometimes met with beatings, whippings, and killings. By contrast, itinerant ministers of the South’s two dominant faiths, Baptist and Methodist, virtually never risked lynching for spreading their beliefs. Southerners apparently reacted not only to the alien content of Mormon theology and religious practice but to the missionaries’ largely northern background and manners as well.

If both law and violent reactions like lynching increase with relational and cultural distance, what factors encourage one rather than the other? Answering that sort of question leads pure sociologists to explore the boundary conditions of earlier theories.

For example, Black proposes that law tends to supplant other modes of conflict management, and because law is less at lower elevations, this helps explain why there is more violent vengeance (self-help) in poor and minority communities. In his book Warriors and Peacemakers, sociologist Mark Cooney combines this idea with Black’s theory of settlement to explain why violence in earlier times was also greater among social elites. For the positive relationship between law and social elevation only holds within the boundary conditions set by the theory of settlement: Settlement is unlikely when the principals are superior to the third party. Aristocrats in premodern times had a violent honor culture similar to that found in modern ghettos, because they were, sociologically speaking, above the law. Rather than submit to the rulings of a mere public servant, they relied on duels, beatings, and private wars. Thus Cooney derives the proposition: “The relationship between violence and third-party status superiority is U-curved.”

Pure sociologists also might specify the relative likelihood of different behaviors along a continuum of elevation, inequality, or distance. In her work on collective violence, Senechal de la Roche proposes that both lynching and rioting increase with distance, but riots tend to occur in more distant conflicts than do lynchings. Likewise, in his theory of genocide, Bradley Campbell says that genocide is a matter of degree, and that the quantity of inequality and social distance predicts the difference between a protogenocide at one end of the continuum and a hypergenocide at the other.

The quest to specify a form of behavior can lead to multidimensional models, in which a certain combination of variable values is necessary to produce a given behavior. Blacks’ theory of blood feuds is an example.

Black defines the classic blood feud as a precise and even exchange of killing, one life for another, taking pace over a prolonged period of time. This is an ideal type, and real patterns of violence might more or less closely match the definition. He proposes that something approaching the ideal type is most likely in conflicts with a certain combination of features:

The classic blood feud is distributed widely in physical space, but its distribution in social space is quite narrow. Everywhere it arises in a distinctive configuration of social distance and social closeness with the following characteristics: The participants are groups largely equal in size and other resources; homogeneous in ethnicity; functionally similar in their activities; mutually independent economically and otherwise; highly solidary in their internal relations; and isolated from one another by an intermediate degree of relational distance, close enough only for mutual recognition. . . No classic blood feud anywhere in the world has had a conflict structure without these elements, which together comprise a stable agglomeration of social islands.

Alter any of these variables, and the resulting behavior deviates from the ideal type. Make the parties less homogeneous and more relationally distant, the violence becomes less restrained and more warlike, with multiple casualties per strike. Make the groups unequal, and the violence becomes more one-sided, with killings on one side going unavenged. Replace groups with atomized individuals, and you have a duel or one-off homicide.

Finally, note that while the locus of explanation in all these examples is the individual instance of conflict, violence, or law, one can aggregate these relationships to make macro-level predictions about what patterns ought to prevail in an entire social setting. Hence my theory of moralistic suicide predicts higher rates of female suicide in patriarchal cultures, where women are apt to be involved in conflicts with a social structure that encourages their suicide. And in Social Structure of Right and Wrong, Black characterizes a series of social fields most conductive to each of his elementary forms of conflict management. For example, avoidance is most frequent and extreme in settings marked by absence of hierarchy, individuation, independence, social fluidity, and social fragmentation.

Beyond Conflict

Even as early as The Behavior of Law, Black was adamant that his paradigm had applications outside of the study of conflict. Though his research program in that topic has produced the most examples of pure sociological explanation, there are examples with other topics as well. Black has theories of God, medicine, and art; Joseph Michalski has a pure sociological theory of welfare, Mark Cooney initiated a pure sociology of predation, and James Tucker adapted Black’s ideas about therapy to explain the rise of New Age religion. But the most highly developed application of pure sociology outside of the study of conflict is Black’s theory of ideas.

In an article “Dreams of Pure Sociology,” Black defines an idea as “a statement about the nature of reality.” Ideas are a form of social life that inhabit a three-sided social structure:

The source of an idea is its agent, the audience anyone to whom it is directed, and the subject anything it describes or explains. The source and audience may be more or less intimate with the subject (relational distance), for example, culturally different (cultural distance), or engage in different activities (functional distance). The source is relationally close to the subject when someone talks about a spouse, friend, himself, or herself, for instance, while a mere acquaintance or stranger is more distant. The relational closeness of the audience to the subject is similarly variable.

Black uses this structure to explain various features of ideas, including what subjects tend to attract ideas in the first place. For example, “the attractiveness of a subject is an inverse function of social distance,” implying a higher rate of ideas about intimates than strangers, about people like ourselves than people different from ourselves, and about humans in general rather than nonhumans. Thus most talk is gossip about people known to the gossipers, and sociologists have a tendency to gravitate toward studying their own contemporary society or segment of society. (See my post “What Do People Have Ideas About?” for more examples.)

Status also matters: “The attractiveness of a subject is a direct function of its social elevation.” Social superiors — especially elites — attract ideas at far higher rates than those of lower standing. Books, magazines, and newspapers deal with their lives, personalities, and behaviors. They’re also more interesting to themselves — they talk about themselves more and are more prone to write autobiographies.

The Behavior of Science

Ideas vary in other ways than their subject, and the social location of the subject help explain this. Some ideas are more scientific than others, defined by the degree to which they’re general, testable, simple, original, and valid. According to Black, the scienticity of an idea “is an inverse function of the social elevation of its subject.”

While people might frequently talk about social elites, ideas about them are relatively unlikely to be testable scientific theories. One reason criminology has more general explanatory theory than other branches of sociology is that it deals with low status people and low status behaviors. But when criminology does address, say, corporate and white-collar crime, it tends to be moralistic and critical rather than explanatory.

Black also proposes that “scienticity is a curvilinear function of the social distance of the subject,” such that, “both very close and very distant subjects attract less scienticity.” At the close end of the curve, people are far less likely to have scientific ideas about subjects that are intimate and similar to themselves. The greater the social closeness, the more likely evaluation rather than explanation, the more likely a narrow explanation rather than a general one, and the more likely the explanation is untestable rather than testable.

Explanations also vary in other ways. Some are deterministic, explaining with forces outside the person or thing being explained. Others are voluntaristic, explaining with what the subject wants or chooses to do. Black proposes that “determinism is a curvilinear function of social distance from the subject,” while “voluntarism is a U-curvilinear function of social distance from the subject.” And “voluntarism is a direct function of the social elevation of the subject,” whereas “determinism is an inverse function of the social elevation of the subject.”

Common sense says that social elites such as kings and generals freely choose to act as they do…But sociology says that the poor and lowly lack free will: Forces beyond their control determine their behavior…The rich who exploit or otherwise victimize the poor have free will, then, but not the poor who victimize the rich.

He applies this to the social geometry of sociological paradigms:

A sociological version of voluntarism is phenomenology—the explanation of human behavior from within the subjective experience of a person. Sociology is more phenomenological when the subject is closer and higher in social space: Phenomenology is a joint function of the social closeness and superiority of the subject. A sociological version of determinism is motivational theory—the explanation of human behavior with the psychological impact of social forces. Sociology is more motivational when the subject is farther away and lower in social space: Motivational theory is a joint function of the social remoteness and inferiority of the subject.

Black’s theory of ideas is a theory of theory, and a theory of why so much sociology is so unscientific. For sociologists are cursed with a closer subject than the non-human sciences: Our fellow people. And lacking a disciplinary identity rooted in studying the past (like historians) or foreign societies (like anthropologists), sociologists were free to pursue the most interesting subjects in their environment: Their own society and segment of society. But the most interesting subjects — the socially close, the socially elevated — are least attractive to scientific ideas:

Sociology took its great leap forward in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—its classical period—when sociologists reached beyond their home societies. Classical sociologists devoured information about past and present societies around the world provided by historians, explorers, missionaries, and other observers. But later sociologists mostly studied their own societies, and comparative and historical sociology became regarded as a specialty . . . modern sociology became less scientific than classical sociology.

. . . modern sociologists have gravitated increasingly to subjects ever closer to their own lives. Many study only their own race, ethnicity, gender, or locality. Once preoccupied with distant subjects below their own social elevation (slum dwellers and poor criminals), they increasingly shifted to closer and higher subjects (professionals and others like themselves) and undermined their scienticity even more.

But the theory of scienticity implies a methodology for making sociological theory more scientific. Black proposes that those who wish to develop sociological theory find subjects in other times and places, periodically move from subject to subject, and avoid first-hand data collection that forces close relationships with the subject. And, of course, he also recommends sociologists follow his paradigm and avoid studying people as such: Instead, study the behavior of social life.

Thanks for reading!

This is the last new paradigm I’ll introduce in this series, but not the last installment. There’s another volume of teaching materials to share, and also a concluding post on “The Lessons of Sociology.”

Once done, I plan to collect this series into a book. Suggestions for revisions, publishers, and marketing are welcome.

Black’s original formulation was that the relationship between law and relational distance was curvilinear. But he predicted the second half the curve only applied to cases that crossed the boundaries between societies, and most legal sociology looks at cases within the same legal system.

This is a simplified version of several propositions from The Behavior of Law. Black later combined them into this single idea in such works as Sociological Justice.

A synonymous term is social control, meaning any act that “defines and responds to deviant behavior.” Hence Black defined law as “governmental social control.” Social control, of course, has at least two other definitions in sociology — as does every other term you can think of. Such are the joys of the so-called discipline.