Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, you can become a subscriber with the button below. You can also leave a one-time tip at this Stripe link.

“It’s a helluva thing, killing a man,” says Clint Eastwood’s character in Unforgiven. “You take away all he’s got, and all he’s ever gonna have.”

Thus most consider the death penalty the harshest sanction meted out in American law. Forbidden completely in some states, in others it is reserved for the worst crimes — not just any murder, but the most egregious cases of murder, such as those carried out in cold blood or that claim multiple victims. And the death penalty looms large in discussions of error and bias in the legal system. It’s especially important to modern jurisprudence that such a severe penalty be applied accurately — that only the guilty be executed — and also that it be applied impartially — that those guilty of like crimes receive like sentences.

Yet it can be hard to predict which cases will result in a death sentence. In their book Geometrical Justice, sociologists Scott Phillips and Mark Cooney challenge the reader with two examples:

Three Jacinto City gang members — Flores, Cruz, and Montoya — meet a young woman named Owens at a McDonald’s. They’re drunk and flirt with her. She agrees to leave and go party with them. They take her back to her house, and then to one of their homes. But after she resists sex with them, they beat her in the head with a golf club and take turns raping her. Then they drive her down the highway, dump her in a ditch, and Flores shoots her in the neck with a rifle. Supposedly he says, “it would be cool to shoot someone” before doing it. The body is found, and all three men are charged with capital murder.

A woman named Adleman leaves her house for a jog one morning. A man named Burton sees her jogging, rides up behind her on his bicycle, jumps her, and drags the screaming woman into the woods. There he chokes her unconscious and takes off her shorts and underwear to rape her. She wakes up and screams, so he chokes her unconscious again, drags her deeper into the woods and strangles her to death with a shoelace. When she’s late coming home, her husband calls the police. They find her body and track down Burton, and prosecutors charge him with capital murder.

The cases seem legally similar; rape or attempted rape followed by murder. They were handled by the same district attorney, and in all cases the offenders were charged with capital murder. But in only one case did the DA follow up by pursuing the death penalty. Which case was it? Why?

According to the sociology of law, the answer depends on facts the written law doesn’t recognize.

Though similar crimes, the social characteristics of the victims were quite different. Owens was a divorced bartender living in a low-income neighborhood. The night of her death, she was engaged in disreputable behavior — leaving her children home alone to have fun with strange drunken men. In the end, the one who shot her pled to a 30-year sentence.

Adleman, on the other hand, was the head of a marketing company — a professional-class woman with a graduate degree and clean record. She was stably married, active in her church, and so esteemed in her community that they erected a memorial on the site of the killing. Her killer was sentenced to death.

Legal Sociology

Phillips and Cooney define the sociology of law as the scientific study of how social factors shape law. They therefore distinguish their endeavor from whatever ideological activism is currently calling itself sociology. Their goal is to deal in empirical facts and falsifiable theories.

They trace the origin of the scientific sociology of law to two sources: American legal realism and the anthropology of law.

American legal realism was a movement within law schools in the early twentieth century. Realists called attention to the gap between law on the books and law in practice, noting that the written rules and legally relevant facts of the case were often not enough to predict what the court would decide.

Legal realism has two main positions: rule skepticism and fact skepticism.

Rule skepticism is the idea that legal rules are ambiguous and open to interpretation. Not only are they filled with vague wiggle words (like the common “reasonable person” standard) but there are usually several potential statutes and precedents that a lawyer or judge or jury might take to be the relevant rule for a given case. See my post on legal realist Fred Rodell’s Woe Unto You, Lawyers! for some rather extreme rule skepticism.

Fact skepticism refers to the idea that even if legal actors have consensus on the relevant rules, the actual facts of the case are open to dispute. Evidence is rarely so strong to remove all doubt, and there’s leeway in which testimony, evidence, or inferences the legal officials accept.

The legal realists made a good case that predicting and explaining legal outcomes required us to look at factors outside of the legal rules and legally recognized facts. And they called for more empirical research on legal cases so we could discover the “real rules” that explained outcomes where the “paper rules” did not. But they never made much progress on that themselves.

The anthropological study of law and conflict also took off around the early 20th century. This would have been back when anthropology was the scientific study of other cultures, not whatever ideological activism is currently calling itself anthropology. Anthropologists like Max Gluckman and Laura Nader examined how people in tribal and traditional settings handled disputes, including community moots, peacemaking by elders, or privately haggling over compensation. These legal anthropologists were very empirical, producing tons of descriptive material on how cases were handled. But they tended to lack theory — any sort of overarching explanation for the facts they described.

The two traditions, legal realism and legal anthropology, fed into a “law and society movement” that straddles the boundary of legal scholarship and sociology. This movement tries to connect empirical research to theory but has an astounding variety of topics. Some study law as an independent variable, examining its effects on other things. Others study law as a dependent variable, asking how society shaped various aspects of law. And within each category there are subjects galore.

Phillips and Cooney stake out their patch within the chaos: They’re concerned with explaining the outcome of cases. To do this, they turn to Donald Black’s sociological theory of law.

The Geometry of Law

Donald Black proposed a general sociological theory of law in his 1976 book The Behavior of Law. The theory purports to explain the handling of legal cases at every phase of the legal process.

Black defines law as “governmental social control.” He conceives of it as a quantitative variable, known by the amount of government authority brought to bear against an alleged deviant. In criminal matters, a call to the police is more law than if they had never been called, an arrest is more than if they hadn’t made an arrest, a conviction is more than an acquittal, and a severe sentence is more law than a light one. In civil matters, filing a suit is more law than not filing one, a judgment for the plaintiff is more than a judgement for the defendant, and a large damage award is more law than a small one.

The quantity of law is his dependent variable, and the central question is why some cases result in more law than others, even when the rules and legally relevant factors appear to be the same.

Black explains such variation with the social structure of the case, defined with variables like the social status of the participants and the social distance between them.

Notably, this is not a theory of the psychology of individual decision-makers in the legal process, but a sociological theory of law itself — he proposes that certain social structures predictably increase or decrease the quantity of law.

Phillips and Cooney boil his original theory down to three core propositions:

Downward law is greater than upward law — crimes by people against their status superiors (upward crimes) tend to be punished more harshly than crimes by people against their status inferiors.

Law varies directly with social status — in cases where the parties are social equals, there will be greater punishment in crimes among the equally high status than among the equally low status. The status of the victim drives much variation in punishment, so that a doctor killing his doctor wife is treated more harshly than a domestic homicide in a minority ghetto.

Law increases with social distance — crimes between relationally distant people attract more law than crimes between relationally close people. Crimes between intimates are punished less harshly than crimes between mere acquaintances, which are in turn punished less harshly than crimes between strangers. Cultural distance is also relevant, and crimes that cross ethnic, religious, or other cultural boundaries tend to get punished more harshly than crimes between people of the same cultural background.

Black later supplemented this with ideas about how the relative social status and distance of jurors and judges could affect outcomes.

Given the language of distance and direction, Black speaks of the social geometry of the legal case. Holding constant the nature of the crime — such as whether it was a theft, rape, or homicide — social geometry predicts punishment.

Social geometry thus predicts the death penalty.

Death Data

Phillips and Cooney discuss the evidence for Black’s theory, saying that the evidence is mixed, but so is the quality of the tests.

This is a perennial problem in sociology and criminology, where researchers are apt to stretch theories in torturous ways to tell a story with whatever data set is at hand. And sometimes testers don’t seem to understand the need to do things like control for the nature of the offense (of course thefts are generally handled differently than murders, so you need to compare thefts with other thefts and murders with other murders) or account for the status characteristics of both accused and victim.

Our authors hold the nature of the offense relatively constant by limiting their analysis to homicide cases. Even more to that, they’re limiting it to homicides that were judged capital murders in their respective jurisdictions.

(For some reason in social science people are really enamored of controlling with statistical control variables. Personally, I think that controlling via sampling is extremely underrated. Purify your sample as much as possible. Instead of constructing complicated models with lots of room for specification errors and p-hacking, take the pains to actually compare like with like.)

The death penalty is controversial in America, not least because of evidence that it’s biased by race and other factors. The upshot is there’s a lot of quantitative data on capital cases. The authors get their data from three big studies:

The Baldus Study, a detailed analysis of a stratified random sample of over 1,000 Georgia murder cases from the 1970s. Baldus and colleagues coded over 200 variables for each case, including characteristics of the accused as well as of the murder victim. And since the cases are several decades old, our authors can even work with an improved database that adds the variable of which death sentences were actually carried out.

The Capital Jury Project, which interviewed 1,100 jurors in 353 capital trials across 14 states. The resulting dataset includes hundreds of variables, and lets our authors investigate how the social characteristics of jurors affect the outcomes.

Phillips’s own previous Houston Study, tracking the outcomes of 504 defendants in Harris County, Texas during the 1990s. He took info from legal, medical, and media sources. They use these especially to find qualitative information on aggravated murders.

Zooming into qualitative case descriptions is often a good idea, if only for a sanity check about what the numbers actually reflect. At several points they give detailed case descriptions to illustrate the kind of variation they’re going to talk about.

Measuring Social Structure

A weird thing about sociology is how few standardized measurements we have. Even ancient people had some rough and ready units for measuring physical distance — often with body parts like hands or feet. Noah could measure his ark in cubits, the distance from elbow to fingertip. But sociologists don’t yet have something comparable for measuring social distance. For the subtype relational distance, we’re stuck comparing broad categories: Intimates versus acquaintances versus strangers.

Here the authors go with a simple dichotomous measure: Whether or not the killer was a stranger to the victim. They leave out cultural distance altogether.

The situation is more complicated when it comes to measuring social status. Black identifies multiple types or dimensions of social status. There’s wealth, obviously, but there’s also respectability (reputation for virtue or deviance), conventionality (having cultural traits that common versus being a minority or weirdo), integration (being at the center of social participation versus being on the margins), and organization (a capacity for collective action that places corporations and governments, as well as their agents, above individuals). Just like we wouldn’t rank the size of objects based entirely on height, ignoring width and depth, we ought to try to take account of all of these dimensions of status.

Imagine you were tasked with measuring temperature in a world where no guys named Celsius or Fahrenheit had ever developed a numerical scale. This leaves you looking for what we call “indicators” of the concept, in this case heat. You make a checklist of signs that something is hotter than other things: steaming water is hotter than water that doesn’t steam, metal that glows red is hotter than metal that doesn’t glow, and if it hurts to touch, then it’s pretty hot.

Regarding status, wealth is the only dimension we commonly measure with any kind of mathematical precision — we can calculate someone’s net worth in dollars or other currency. But court records aren’t going to give you anything that precise for the parties in a capital murder case, so even for wealth we must turn to rougher indicators.

Phillips and Cooney settle on the following: A person is counted as having greater wealth if they have a professional job, they’re counted as being more integrated if they’re a parent with a dependent child, they’re counted as more conventional if their race is listed as white, they’re counted as more respectable if they have a clean legal record, and they’re counted as being more organized if they’re a state official.

Based on these variables, the authors give each killer and victim a status score. They classify the average score for both killers and victims. Killers, not surprisingly, tend to be low status — unemployed guys with long rap sheets, and disproportionately racial minorities. Their victims often have similar characteristics, and the authors note few of the people involved in these cases would qualify as “high status” in society at large. But to try to get at relative differences, the authors grade them on a curve. They classify a killer as high status if they’re above the average for killers. They likewise classify victims as high status if they’re above the average for victims.

I’ve thought since grad school that measurement was a major stumbling block to scientific sociology. This is especially so since we’re often reduced to using data initially gathered for bureaucratic or legal purposes. At the root of all these measures are things that state officials deem worthy of recording, and none of those officials were concerned with testing a sociological theory of law. So while the authors clearly understand the theory and are choosing indicators that make sense for the concepts, they’re limited to what in the grand scheme of things are very rough measures.

For instance, race does tap into conventionality. But of course, both white and nonwhite might include people who speak with American accents and wear common fashions, versus people who are recent immigrants or wear distinctive ethnic garb. And I’m pretty sure a Chasidic Jew would probably stand out more to a Houston jury than a working-class black guy who goes to the Baptist church on Christmas.

On the other hand, race is also picking up other elements of status, such as the fact that blacks on average have lower incomes and are more likely to have criminal records. If blacks make up a large proportion of nonwhites, this weakens it as a specific indicator of conventionality, though perhaps that makes it a better indicator of status overall and helps more than it hurts in this index. But more on that later.

I’m not throwing shade. We all face the same sorts of restrictions in our work, and I’m a lesser methodologist than these guys. Unless some influential billionaire takes an interest in pure sociology, getting large samples means using the best indicators available, not the best ones you can think of. But I do lament these limitations and think we should be mindful of them when judging findings.

Patterns in Death Sentences

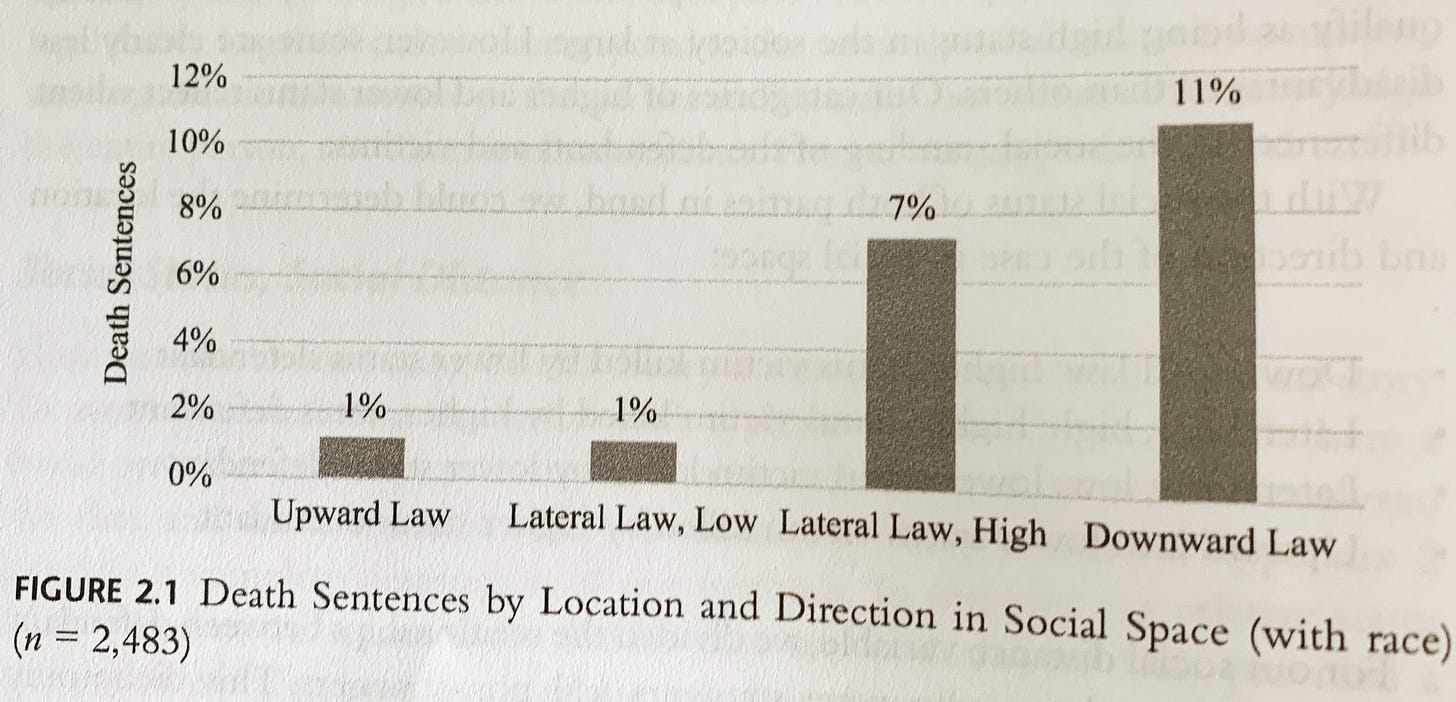

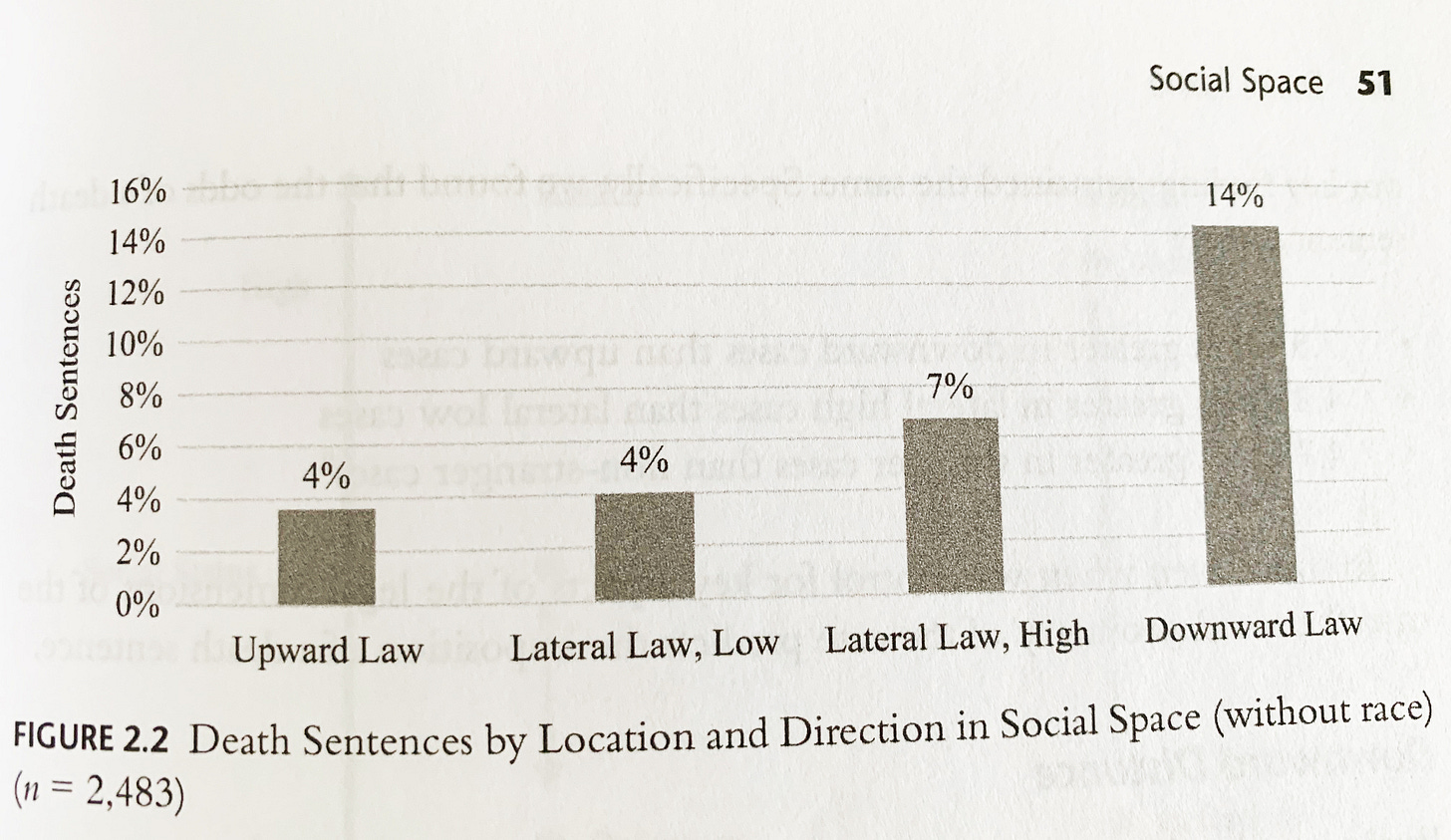

Black predicts that upward killings (downward law) are more likely to produce a death sentence than are downward killings (upward law), and that killings between equally high-status people are more likely to produce the death sentence than killings between equally low status people.

He combines these ideas to predict a four-fold pattern: Legal severity should be greatest in upward killings, followed in order of decreasing severity by high lateral killings, low lateral killings, and downward killings.

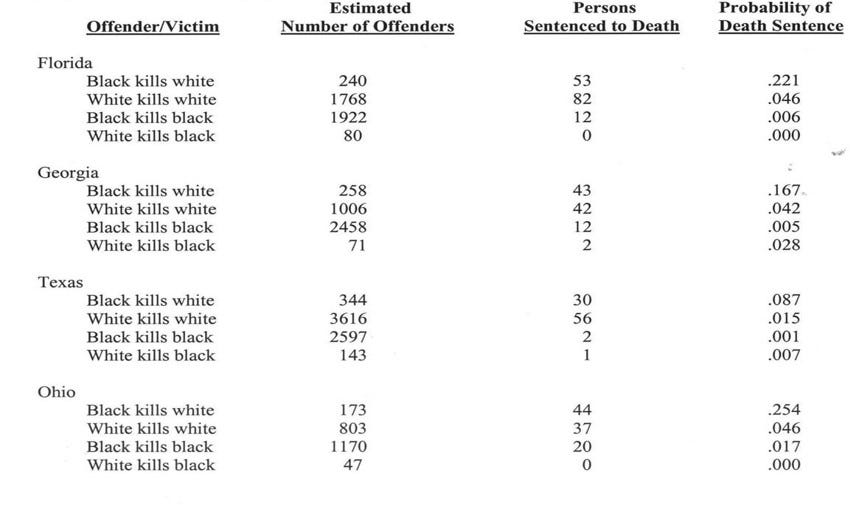

If we accept race as a proxy for various kinds of social status, older death penalty studies more or less match this pattern:

That table is from a 1980 study by Bowers and Pierce. The 4-fold prediction holds for at least Florida and Ohio. Aside from providing evidence for Black’s theory, it also shows the importance of taking account of both killer and victim when looking for social bias in sentencing. If you just looked at race of offender, you wouldn’t see much variation except for some slight leniency for black offenders (who tend to kill black victims).

In their own data, Phillips and Cooney also find a pattern that is close to Black’s prediction, but not quite identical. As predicted, upward killings (downward law) are more likely to result in the death penalty than are downward killings (upward law). And in lateral cases, those involving high status killer and victim were more likely to produce the death penalty than cases between low status people.

These relationships hold controlling for whether the killing was deliberated, a measure of how many kinds of evidence were introduced against the defendant, year of sentencing, and social distance.

People usually only talk about this stuff in terms of race, and as noted race as a variable might be picking up other things. So they authors run a version of the analysis where they drop race as an indicator, and just use the other status variables. Notably, the same patterns hold. I actually think that finding ought to get more attention: Other measures of status are enough to account for substantial differences in the odds of a death sentence. People who only focus on race are missing a big chunk of the story.

Where their finding deviates from the 4-fold pattern is that there wasn’t a difference between low-kills-low and high-kills-low. (Note those two categories also didn’t rank right for two states in the Bowers and Pierce study cited above.)

I think it’s worth calling attention to, just because it’s so rare to have a theory in sociology that makes a prediction that is this precise. Sure, it’s not mathematical precision. But virtually all sociological theories are at the ordinal level of measurement, predicting what should be greater or lesser from one condition to the next. A theory that rank-orders four different categories counts as a gutsy called shot by this standard.

One value of precise predictions is to increase testability — the theory is more falsifiable because there are more ways for reality to contradict it. And even if a theory seems largely correct, and we’re tempted to say, “close enough, substantially supported,” it’s those points of friction with reality where the puzzle-solving of normal science takes place. So I think it’s important to drill down on why that one particular aspect of the rank-ordering didn’t pan out. It could be that the theory needs revision, but could also be we need better data.

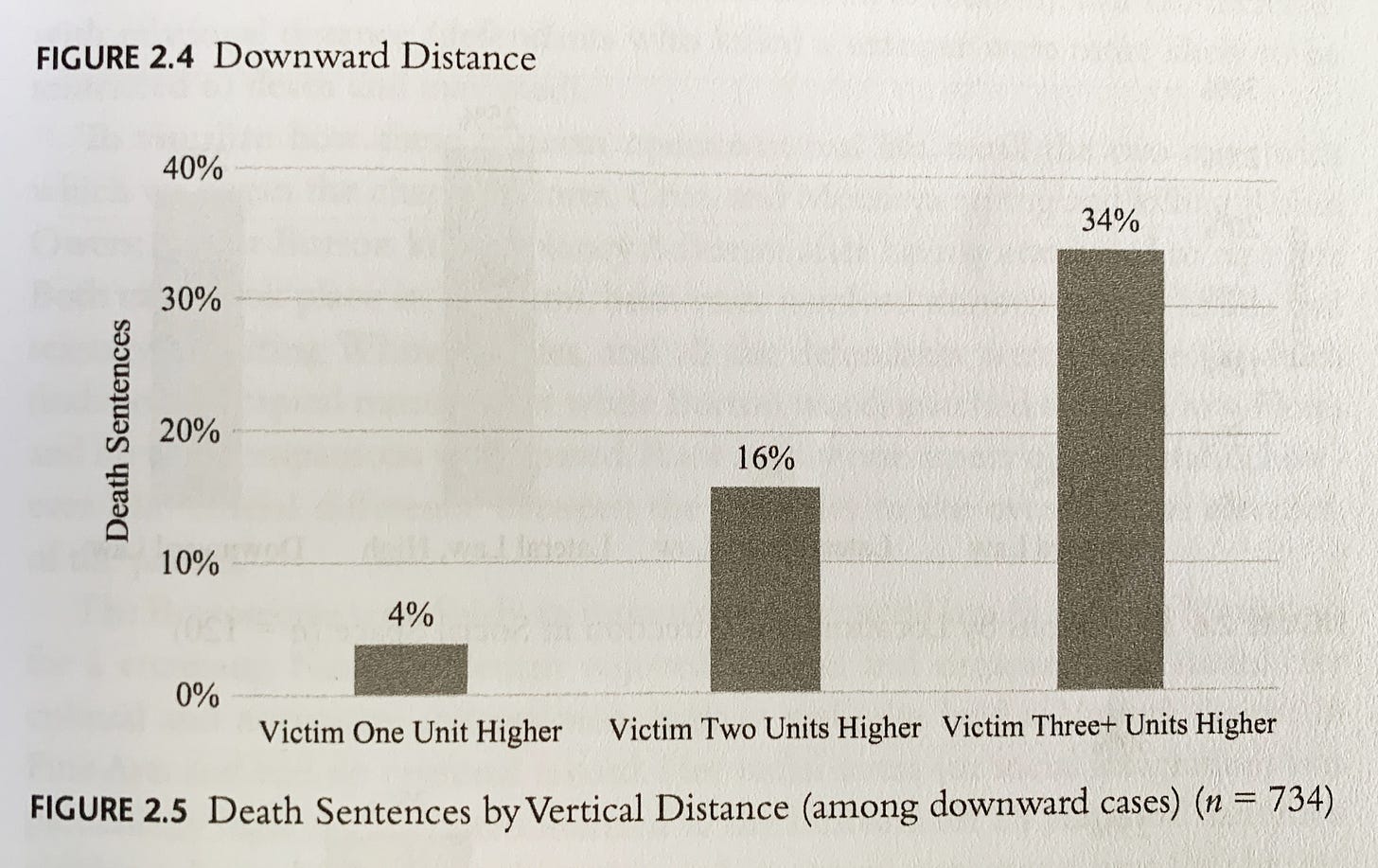

I asked the authors about this at a criminology conference and Phillips said he thinks it’s a data issue. Downward killings are actually pretty rare in contemporary America: Only 172 of their 2,483 killings were downward (and thus upward law). And the degree of vertical distance was low — we’re not talking cases of a CEO offing a vagrant. It’s likely there’s just not enough variation in the sample to get a strong signal. Though you can see a clearer relationship if you look at settings where downward violence was more common and extreme, like in aristocratic or slave societies of earlier historical periods. (See Cooney’s book Is Killing Wrong? for examples of this.)

Speaking of downward distance: According to Black’s theory, it should indeed matter. The authors test this by subtracting the status score of the offender from that of the victim in case where the victim was higher. Thus they are able to classify degrees of vertical distance from one case to another. Say a black guy kills a white guy, but they’re both nonprofessionals with criminal records and aren’t family men — this is a one-unit gap, as its only upward in the sense of being minority against majority, but not along any other dimensions of status. But if victim also has a clean record and was supporting a family, he’d be three units higher.

The authors find that the odds of the death penalty increase as the status gap grows, being just 4% if the victim is one point higher but 34% if the victim is three or more points higher. Keep in mind “downward cases” here means downward law (a response to an upward killing).

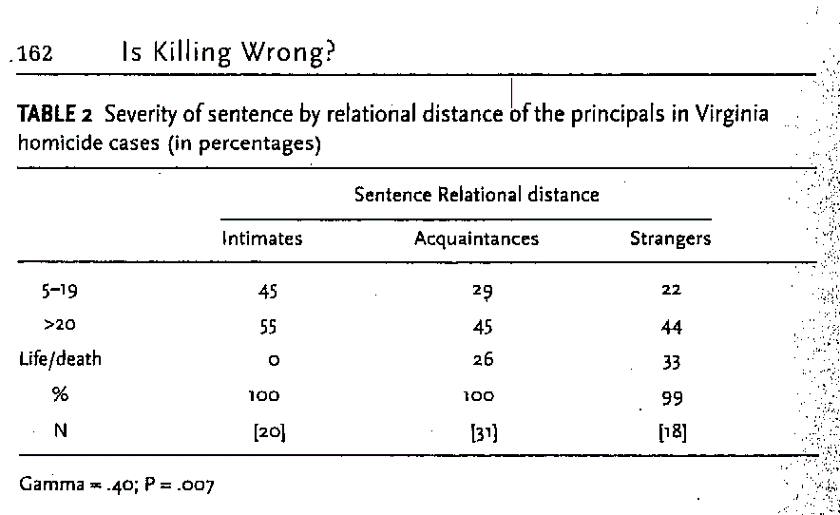

We’ve talked a lot about status and how to measure it. And indeed, when people talk about discrimination of biases in the legal system, they tend to focus on social status (well, mostly just on race, but they’re usually thinking of race as a form of status). Yet Blacks’ theory predicts that the social distance between the parties, including their relational distance, is just as fateful to how a case is handled. One of the greatest sources of inequality before the law is whether or not you were victimized by an intimate. See this table from Cooney’s book Is Killing Wrong?, showing the outcome of homicides in Virginia:

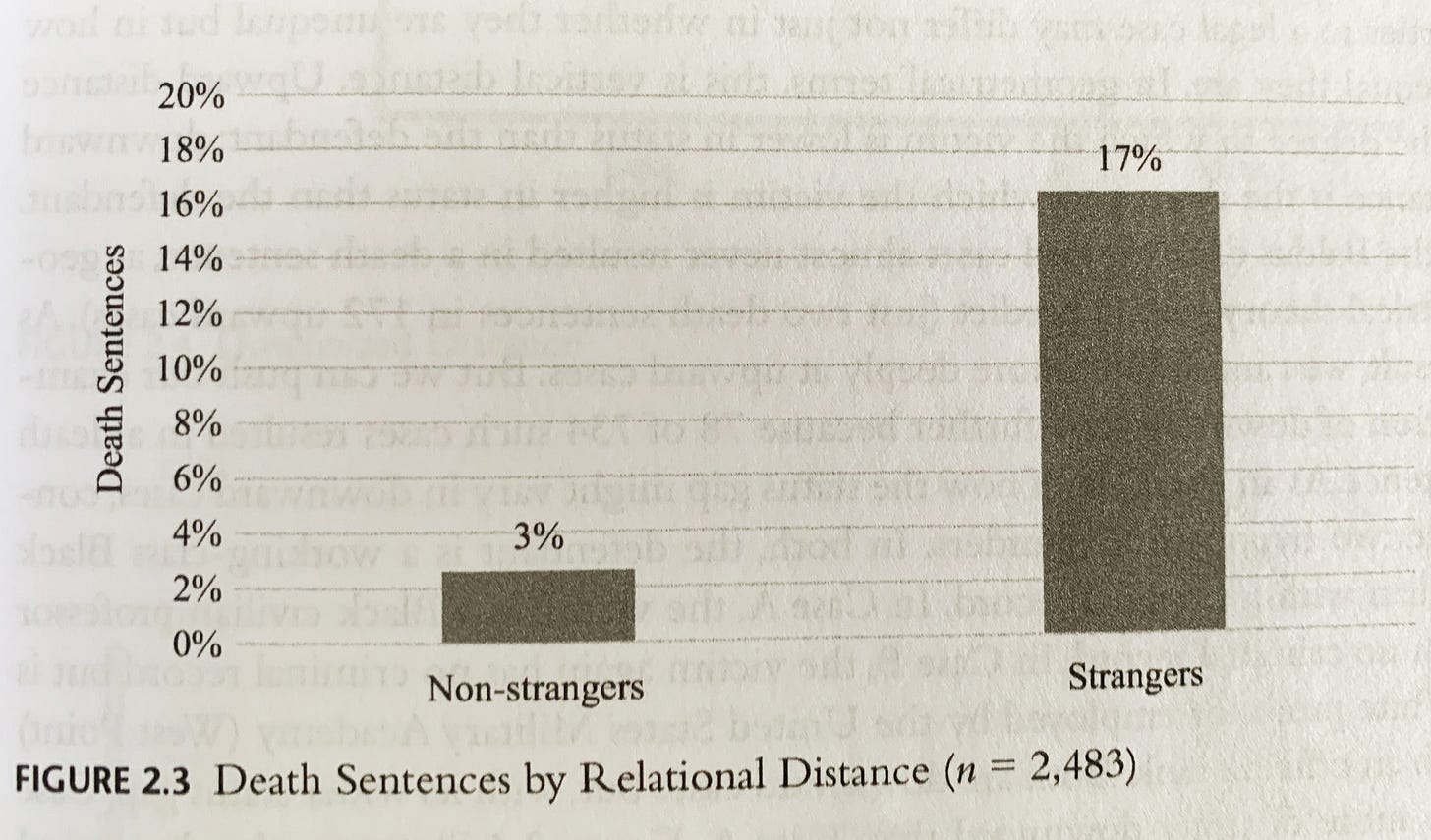

Phillips and Cooney’s current results show that relational distance matters greatly in capital crimes: The death penalty is nearly five times more likely for stranger killings than non-stranger killings.

This holds when controlling for status effects and for factors like premeditation or strength of legal evidence.

Law as Partisanship

I’m not going to cover every single aspect of the book here. The authors also examine things like whether these same variables predict which sentences are actually carried out (versus being successfully appealed). They draw from another of Black’s theories to see how the nature of the killing — such as whether it involves kidnapping or torture — predicts the death penalty. They examine the voting patterns of jurors and find that high-status jurors are more likely to vote for death. They conclude by suggesting ways to reduce social disparities in the death penalty, as well as examining the causes of the decline of the death penalty in America. I suggest giving the book a closer look if you’re curious about any of that.

But I do want to mention some ideas from their chapter on third parties. Both of these guys have done innovative and important work on the role of third parties in shaping conflicts. (See especially this article and this book.) And we can often model law itself as a third party getting involved in a conflict between two side — in homicide cases, its intervening in a conflict between the killer and the victim.

In his theory of partisanship, Black proposes that the degree to which a third party takes one side against the other is a joint function of closeness to one side and distance from the other, as well as the superiority of one side and the inferiority of the other.

In the context of law, partisanship shapes the behavior of judges and jurors — who are likely to be harsher when they have some sort of relational or cultural ties to the victim, but not to the accused. It also shapes the behavior of other legal officials, including the police officers who investigate the crime and the prosecutors who set the charges.

For instance, when the victim is a police officer — someone with organizational ties to those doing the investigating and prosecuting — the odds of the death penalty are higher. According to the authors, this is driven by prosecutors recommending these cases for the death penalty at far higher rates, and only partially corrected by jurors who, with fewer ties to law enforcement, have higher standards for imposing the death penalty in these cases.

Regarding the effects of partisanship on investigation, we find ourselves back at the legal realist’s doctrine of fact skepticism. Investigators do not put the same effort into every homicide case, nor are witnesses always willing to testify. And these differences are not randomly distributed.

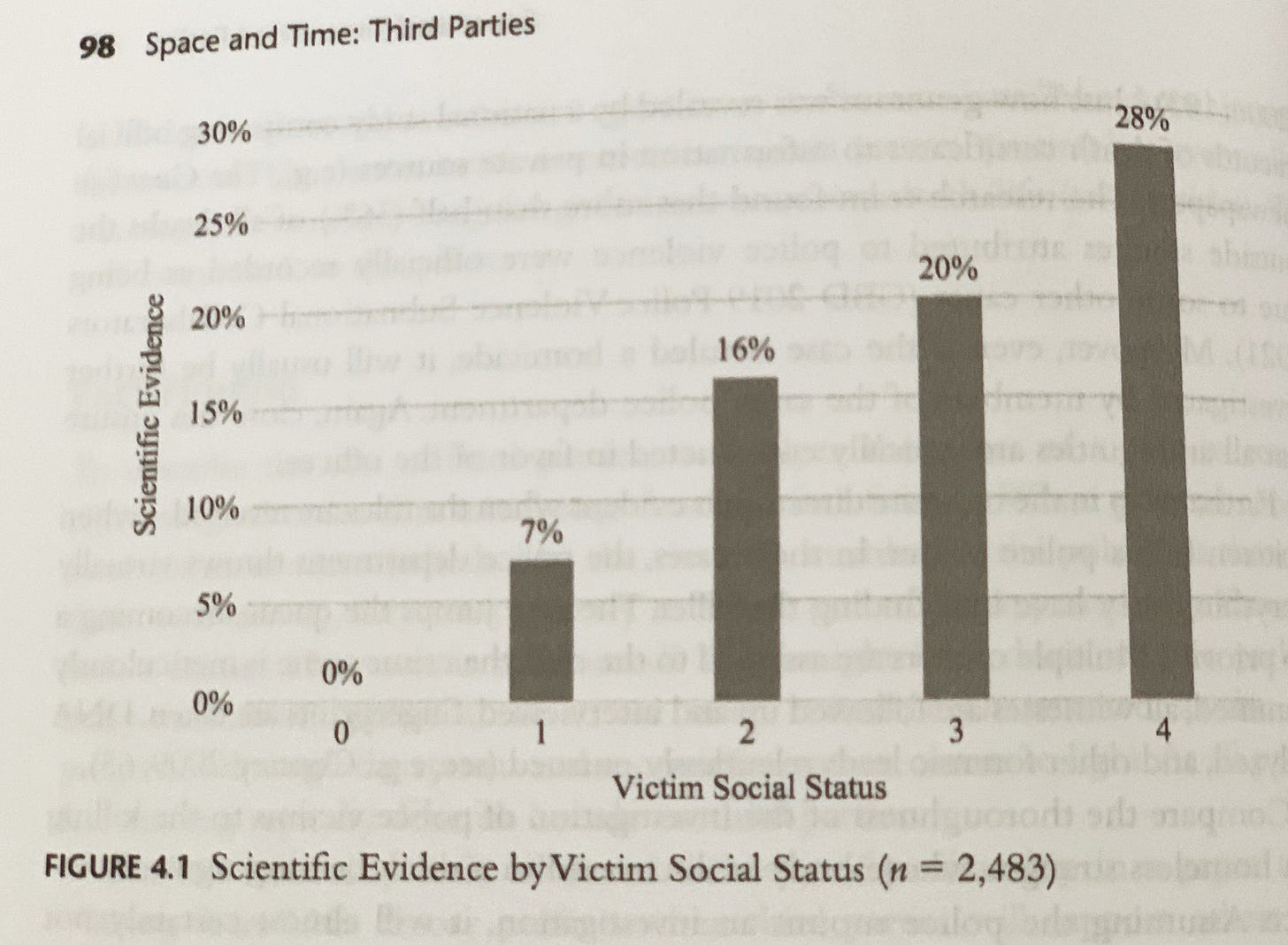

The authors report one fascinating finding in this regard: Police investigators are more likely to generate scientific evidence like fingerprint analysis or tire track analysis when the case as a higher status victim, as measured by their index of social status. For their top status category, 28 percent of cases produce evidence of this kind, while for their bottom status category absolutely none do.

They also note that cases where the victim has close ties to the police, especially if the victim is a police officer, tend to generate much more extensive investigation. (See also Cooney’s classic article, “Evidence as Partisanship.”)

As the authors acknowledge, this somewhat complicates our model of social factors having an impact when all else is equal. For one of the things that we’d like to hold equal is the legal evidence of guilt. Yet the evidence itself is socially patterned. Which in turn might have methodological implications, as it means some of our estimates of the influence of social factors are actually on the conservative side. Justice isn’t blind, but it is geometrical.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber at the link below. I also appreciate anything left in the Tip Jar.