Explaining Behavior 12: Conflict Theory

Society as struggle between oppressor and oppressed

This is part of a series on how to explain human behavior. It is based on a course developed by the late Donald Black at the University of Virginia. You can read each part independently.

Parts 1 through 6 discussed the general logic of scientific theory. From Part 7 onward we cover different strategies or paradigms for developing explanations. The last installment was Part 11: Functionalism.

In their political pamphlet The Manifesto of the Communist Party, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Every society in history, they said, has a dominant class and a subordinate class — “freeman and slave, patrician and plebian, lord and serf, guild-master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed.”

The interests of dominant and subordinate classes are naturally opposed, leading to struggle between them. These struggles sometimes fester quietly. Sometimes they erupt into open conflict. And occasionally they lead to a full-scale revolution that ushers in a new economic system and establishes a new ruling class.

In the modern world, our economic system is capitalism, and the ruling class is the owners of productive capital — the mines, mills, and factories. The oppressed class is the workers who labor at these mines, mills, and factories.

Owners exploit the workers. Capitalist profit is essentially a form of theft: How else could they make money if they weren’t taking more value from the worker’s labor than the worker was paid for it?

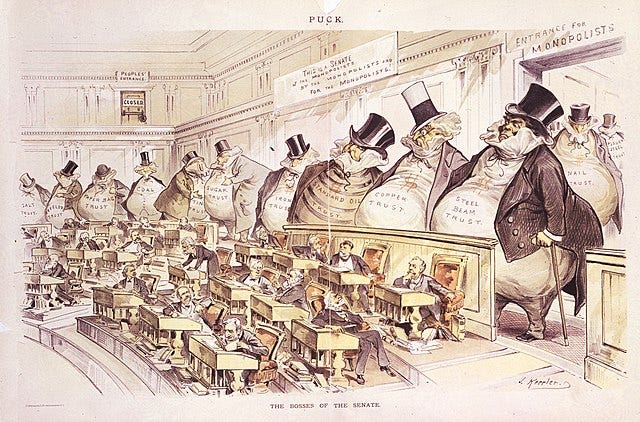

And owners are able to organize all of society to further this exploitation, with social institutions — law, custom, religion — working to uphold their interests and stack the deck in their favor.

But the system is unstable. Capitalists compete with each other, and some inevitably lose. The ranks of workers are constantly swelled with those who’ve been driven out of business, cast down and forced to labor for a wage.

Furthermore, owners who wish to stay in business must constantly make their mines, mills, and factories more efficient. They invent new technologies and learn to create more product with less labor. Thus workers are constantly thrown into the ranks of the unemployed. As this “industrial reserve army” of unemployed workers grows, it gives owners the leverage to drive wages down to bare subsistence level.

Capitalism concentrates these growing masses of miserable workers together. The vast scale of modern industry spawns entire factory towns where workers live cheek to jowl in poor conditions. This encourages them to develop a common identity and perceive their common interests. It also facilitates them organizing to pursue these interests.

The inevitable result will be that the impoverished workers revolt and overthrow the capitalists. The workers will then seize the means of production for themselves. Only instead of becoming a new ruling class — as did every other victorious class in history — they will abolish private property and see to it that everyone has what he needs. There will be no more classes and no more class struggle. The world will become a giant commune. There will be utopia.

If you believe that prophecy, then I’ve got a bridge in Brooklyn to sell you. And attempts to bring about this utopia have killed many tens of millions. The Manifesto might be the single deadliest document in human history.

But social class is real phenomenon, is it not? Don’t different classes have different interests? Don’t elites have greater ability to get their way?

Even those who reject key tenets of Marxian theory might see some value in its broader strategy for analyzing society.

The Conflict Paradigm

Conflict theories, as Donald Black defines them, explain behavior with the struggle for domination.

He and others also call this paradigm neoMarxian theory, as it originated in Marx’s theory of class conflict. Both terms are fairly common, and I go back and forth on which I prefer. What people call critical theories also fall within this paradigm. The latter term has gained popularity in the past decade, and one frequently hears about critical race theory or even critical criminology.

Various conflict theories differ in their specifics, but according to Black they all share four major assumptions:

Different social categories have inherently different interests. The inherent part is important, as these interests are said to be objective consequences of social structure. If your subjective preferences differ from what the conflict theorist says your objective interests are, you suffer from false consciousness — you’ve been duped into not recognizing your own interests.

The clash of interests is zero-sum: One group’s gain must be another’s loss. Thus if owners make profit, workers must be losing something. I doubt most conflict theorists deny the possibility of positive-sum (win-win) games, but they almost never see them in the social arrangements they are analyzing.

Over the long term, elites dominate nonelites. You might think this inheres in the concept of elite, but other paradigms don’t necessarily assume that greater stature implies domination in the sense of overriding the will or interests of nonelites.

Only radical change can substantially reduce the domination of current elites. In classical Marxism, this was violent political revolution leading to the overthrow of the current ruling class. Others are less violent and less utopian, but generally they posit some major reworking of social institutions or individual consciousness as the only way to overcome a system of oppression.

These four assumptions describe the basic logic of Marxian theory, and also the logic of various neoMarxian conflict or critical theories.

Black classified conflict theories as a breed of utilitarianism, alongside the rational choice paradigm. The idea was that both rational choice and conflict theorists analyze social life in terms of the selfish pursuit of interests. Conflict theory differs in its focus on collective rather than individual interests and its assumption of zero-sum clashes resolved by domination.

In sociology courses and textbooks, the conflict paradigm is often contrasted with the functionalist paradigm. They’re taught as a kind of opposing pair — one is conservative and emphasizes cooperation, while the other is radical and emphasizes struggle.

But I’ve long thought the two paradigms share key similarities. Both focus on collective teleology, asking what good some social pattern achieves for a group. In the simplest and laziest examples, the explanation is purely teleological — one explains something simply by identifying the purpose it serves, whether for society as a whole or for the ruling class. And for both paradigms, these tendencies limit falsifiability and explanatory power — in practice, neither has a good track record of explaining variation with testable propositions.

Consider how this works with Marx’s theory of class conflict.

Classical Marxian Explanation

Much of Marx’s voluminous writing is, when not ideology, metatheory. This includes his famous arguments for sociological materialism — that any theory of society ought to start by analyzing economic conditions, since this economic “base” shapes all other social activity.

When one finds explanations in Marx, they involve specifying how some facet of society contributes to class struggle — usually, how it upholds the dominance of the elite and furthers exploitation of the workers.

For example, Marx famously called religion “the opium of the people.” The idea is that religion exists in order to placate the masses by offering them promises of just reward in the afterlife. After all, isn’t “blessed are the meek” just the sort of idea that elites would want to encourage among their impoverished subordinates?

Marx also held that the state exists in order to serve the interests of the ruling class — that is it no more than the “committee” for managing their affairs. Therefore, law operates to maintain their dominance.

Legal bias in their favor is both substantive and procedural. The law favors the ruling class in substance when the content of legal rules limits the rights of workers. For instance, during historical periods of labor shortages, states have passed maximum wage laws to limit how much workers can demand for their labor.

The law is biased in is procedure when, regardless of written content, it operates in a way that favors the owning class. For instance, while English law specified a minimum working age for industrial laborers, in practice the doctors charged with verifying the age of laborers would routinely lie.

According to Marx, even legal arrangements that seem to guarantee equal rights actually mask and therefore facilitate domination. Consider contract law, which assumes both parties freely negotiate the terms of the contract. In reality, the parties are often so highly unequal that one side is effectively dictating terms: The mine owner can find a new miner far more easily than the miner can find a new mine, and the mine might be the only employment in the area. Viewing employee-employer relations as a free contract just gives the worker freedom to be exploited.

In this way, Marxian theory often claims to ummask social arrangements, revealing their true and exploitative nature.

The core shortcoming of Marx’s explanation of law is that it makes few if any predictions about what the law will actually do, or not do. It does not explain when a state will enforce minimum wage or workplace safety laws and when it will not. We see both empirically — why the difference? One can make a similar criticism of his takes on religion or ideology. When will the ruling class maintain their dominance by doing X rather than Y?

It is, however, easy to give Marxian interpretations in hindsight. Philosopher Karl Popper complained that the committed Marxist can explain completely opposite outcomes with equal facility. So, the state is now allowing unions and limiting working hours and mandating a minimum wage? Very sneaky! It’s actually upholding the interests of the owners in a roundabout way, throwing a bone to the workers in order to forestall the revolution.

There’s a large degree of freedom in imputing interests, and one can readily switch between long-term and short-term ones, or else argue that an apparent victory for workers is only a temporary blip on the road to their prophesied immiseration. This “escape hatch,” as Black called it, is a major problem.

When Prophecy Fails

In addition to explaining his own contemporary society, Marx also forecast social change: Hence his idea that class polarization and the immiseration of the working class would lead to the great global revolution. Writing in the middle of the 19th century, Marx saw future economic development as being something like the worst aspects of early English industrial towns, magnified and multiplied.

Yet instead of steady polarization, the capitalist countries saw the growth of a middle class. They also saw the growth of welfare states. And instead of privation, their working and lower classes now suffer from diseases of affluence like obesity and easy access to drugs — even in the 1990s, writer Daniel Quinn remarked that Marx failed to foresee a day when the opium of the people was actual opium. Communist revolutions also only happened in the exact places he thought they would not — backward agrarian economies like Czarist Russia. And then there were the complications to his owner/worker dichotomy caused by creation of stock markets — if Mom’s retirement fund invests in a portfolio of companies, does that make her a capitalist?

There are two reactions when observations are contrary to expectation. One is the reaction of true believers: All things can be interpreted in accordance with the theory, if you’re just willing to do enough interpretive work. Popper said the Marxists he knew in 1920s Vienna did this, and transformed what might charitably be called a testable-but-wrong account into a not-even-wrong faith.

The other route is to acknowledge there is a problem and revise the theory. Some neoMarxian scholars, for instance, stick with the focus on class conflict but deviate from Marx’s stringent materialism. The neoMarxian Frankfurt School took this path, arguing that capitalist ideology was more powerful than Marx realized. I don’t think they produced much testable explanation of their own — and Popper savaged them for dressing up empty statements in fancy jargon — but at least they recognized that things weren’t going according to plan.

Others revise Marx by reconsidering the notion that the state is a mere appendage of the ruling class. Maybe the state should be understood as a distinct entity with its own interests that aren’t perfectly aligned with any of society’s economic classes. It’s not just a battlefield for social actors, but an actor itself.

Still others complicate their models of class. The NeoMarxian sociologist Erik Olin Wright came up with an expanded set of 12 categories based not just on ownership but on control and skill: “expert managers” are different than “skilled managers” are different than “skilled workers” and so on. But there’s evidence these categories aren’t very useful for predicting differences in behavior or beliefs.

Beyond Class

Most modern conflict theories eschew Marx’s narrow focus on capital ownership as the main division of modern society. In Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society, Ralf Dahrendorf said ownership of capital mattered less than the distribution of authority. C. Wright Mills said the bigwigs of industry, the military, and politics were all part of The Power Elite that dominated average Joe and Jane. In Immanuel Wallerstein’s “world systems theory,” the classes aren’t composed of individual persons at all, but of nations, with wealthy core nations dominating and exploiting peripheral nations.

Still others look at groups defined by prestige, by education, and, of course, by various identity categories like race, sex, and sexuality.

This includes a good deal of modern feminist and gender theory. Not all of it — some of what people refer to with these terms is phenomenology (looking at how men and women view the world differently) or motivational theory (looking at gender socialization). But much is conflict theory, with gender and sexuality supplying the relevant oppressor and oppressed categories.

This is especially apparent in Catherine MacKinnon’s Toward a Feminist Theory of the State. Her argument is much the same as Marx’s, but with sex instead of class. Thus she argues that law supports the interests of all men against all women through various pro-male biases. For instance, rape is a tool by which men as a class dominate women as a class, and the law treats rape accordingly, making it difficult for rape victims to get justice and easy for rapists to get acquitted. And the bias might even be subtler, as even consensual sex is suspect in a society where women aren’t truly free to consent.

In the last decade or so, critical analyses of race, gender, and sexuality have exploded in prominence, both within the academy and outside of it. Some focus mainly on one of these categories, but the term intersectionality has come into fashion as a way of incorporating all of them.

When I first heard this term late in my graduate career, I took it as newfangled jargon for a statistical interaction effect: If being a woman disadvantages you, and being black also disadvantages you, then being a black woman extra disadvantages you. But it seems there’s a deeper claim that all these forms of oppression are fundamentally related — “interlocking” is a common term — and that they cannot be understood or combatted in isolation. A friend jokingly parsed it as the discovery of a fundamental “oppression stuff” that permeates various aspects of society.

I don’t find the flood of fashionable critical theory impressive from a scientific point of view. And it’s become so part of the zeitgeist, so institutionalized in academia and elsewhere, that it’s not very informative for my students to hear about it again. So when I discuss the conflict paradigm, I try to focus on ideas that are more scientifically promising, or at least that they probably haven’t heard before. First, I introduce them to a conflict explanation of why Marxism failed.

The Iron Law of Oligarchy

In his 1911 book Political Parties, sociologist Robert Michels proclaimed, “Who says organization, says oligarchy.” The idea is that any sufficiently organized group will have leaders: Presidents, treasurers, secretaries, and the like. Even political parties that are dedicated to pursuing democratic and egalitarian ends must, by virtue of organizing to pursue them, produce a small number of members who have far more influence than others over what the organization does. This is the oligarchy.

The interests of these oligarchs are not identical to the interests of the rank-and-file. Even if all members of the organization start out as broadly the same — all socialist workers or whatever — the leadership, by virtue of being leaders, have different activities, opportunities, concerns. If nothing else, they’ll look out for their own children first and be better positioned to use organization resources to do so.

Marx was naïve to think that state-ownership of the means of production would lead to a classless society. Michels writes:

It is none the less true that social wealth cannot be satisfactorily administered in any other manner than by the creation of an extensive bureaucracy. In this way we are led by an inevitable logic to the flat denial of the possibility of a state without classes. The administration of an immeasurably large capital, above all when this capital is collective property, confers upon the administrator influence at least equal to that possessed by the private owner of capital.

Another way of saying the state owns the capital is to say that the people who run the state own it. Congratulations, there’s your new ownership class. And why would it be any more saintly than the old one?

Thus “really existing socialist societies” had a starkly unequal distribution of resources. The Communist Party oligarchs had access to luxuries like vodka and caviar and nice dachas in the country. Those less connected to the centers of power might not have food at all, perishing with their families in times of famine.

Materialist Theories of Stratification

Conflict theorists are concerned with social stratification — inequality of wealth, power, and status. But relatively few of them actually explain variation in it. Why are some societies fairly egalitarian, but others have distinct social classes like noble and commoner?

Sociologist Gerhard Lenski, in his book Power and Privilege, saw himself as combining elements of functionalism and conflict theory to answer this question. He thought people cooperate under certain conditions, compete under others. When resources are scarce and variable, norms of sharing and reciprocity are a good risk buffer for everyone. But in societies with a stable economic surplus, people are prone to struggle for control of it. As they do this, they naturally form factions. And initial advantage in getting control of economic surplus tends to produce further advantage: If you can wrest control of some surplus, you can use it to pay ruffians to help you get more.

Hence his idea that, all else equal, social stratification is a direct function of economic surplus. He said this explains that tendency of social stratification to increase as productive technology develops. Foraging bands have little stored food or goods, and little inequality between families. In horticultural societies we start to see chiefs, big men, and, in some of the more advanced cases, the beginnings of nobility and enslavement. In societies with intensive agriculture, we see a God-Emperor at the top, and he and tiny minority of high-ranking nobles and priests control the vast majority of wealth and political power. They rule over a mass of peasants and slaves — the latter being up to a third of the population in ancient Rome.

The “all else equal” part is important, though, as throughout the book he introduces other variables — like the military participation ratio — that also affect the quantity of stratification. And he tries to explain why, despite the fantastic economic surplus of modern industrial society, it’s far less stratified than ancient empires.

Lenski follows Marx in his materialist focus on how the “techno-economic base” shapes other aspects of society. Sociologist Rae Lesser Blumberg follows Lenski in applying this same approach to inequality between the sexes. In her “General Theory of Gender Stratification,” the core proposition is that that women have greater overall stature — including greater personal autonomy — when they, on average, control more of a society’s economic surplus.

What I think makes her work better than most conflict theories is that she goes on to formulate propositions about which aspects of economic production and social organization predict greater female control of surplus. For instance, she connects female status to the degree to which the main mode of production requires upper body strength, such that women’s relative status is usually very low in societies based on plow agriculture.

While one can criticize her many propositions, they at least attempt to explain variation. The theory also has admirable generality, dealing with the range in the relative status of the sexes across different types of society. Some sociologists who talk about “patriarchy” seem incapable of recognizing that it is a variable, and that modern America is not at the high end of the scale. Aside from an unfortunately credulous reference to the egalitarian Tasaday — which turned out to be an anthropological hoax — the engagement with cross-cultural literature is admirable.

In a subsequent publication, Blumberg applies the theory to explaining differences between different types of agrarian society. And the theory appears to stand up pretty well in at least one cross-cultural test by another researcher.

Professions and Schools

Sociologist Randall Collins is unusual in being both an advocate for conflict theory and for sociology being more scientific. See, for instance, the title and subtitle of his early book Conflict Sociology: Toward an Explanatory Science.

Collins sees in human societies struggles between various groups. For instance, in his book The Credential Society (which I review here), Collins tries to explain the great expansion of schooling in modern America. The expansion was driven in large part by rising educational requirements for high status professions. And those were driven, he claims, by a kind of arms race between different interest groups.

The earliest expansion of credential inflation in the US was driven by white Anglo-Saxon Protestants trying to keep the ethnic riffraff out of high-status professions like law and medicine. But the relevant interest groups aren’t just ethnic or religious. All members of the profession, whatever their background, have an interest in maintaining a wide and deep moat. Elite status — and high income — depend in part on the scarcity of personnel. And educational requirements are a wonderful barrier to entry. Why does anyone need to go through four years of general education requirements before they start learning the law? Because it’s to the advantage of lawyers, and lawyers can pressure the state to make rules in their favor. The medical cartel similarly limits the number of doctors.

Collins also observes that the credentialed class as a whole is increasingly a distinct status group with their own interests. And it seems, fifty years after the book was published, college versus non-college predicts a lot more about belief and behavior than complex class schemes based on roles in economic production.

But what I think makes Collins’s book better than many other examples of conflict theory is that it doesn’t rest solely on identifying the “function” of credentialism. Along the way he explains variation in the proliferation of schools (which varies with wealth, diversity, and political centralization) or the ability of some occupations to become “strong” professions that successfully regulate their membership (which varies with predictability and observability of output). Like Lenski and Blumberg, he’s got propositions.

In his Sociology of Philosophies, Collins saw philosophical schools as competing interest groups locked in a struggle to command shares of a limited attention-space, with winners getting honors, patronage, and students at the expense of losers. The history of philosophy is the history of intellectual conflict.

Marx thought society evolved through contradiction. He got the idea from the philosopher Hegel, and Hegel probably got it from the way philosophy itself evolves. For if there’s already a philosophical school hogging the majority of attention-space, there’s little alpha in saying, “Yes, I agree.” The best strategy to make your mark is to stand in opposition.

The result is what Collins calls the “intellectual law of small numbers,” that “the number of active schools of thought which reproduce themselves for more than one or two generations in an argumentative community is on the order of three to six.” You’re almost guaranteed three: School A, the opposing school B, and School C saying, “a plague on both your houses.” Maybe there’s enough resources left over of a few rump schools, but the tendency is for weaker schools to coalesce into more formidable ones. And if one school ever achieves dominance, rival factions within it soon produce a split.

Of particular interest is his theory of why modern science does not follow this dynamic: The pace of empirical discovery increased enough to support a new form of status competition, where rewards came from novelty rather than contradiction. It’s something analogous to capitalism breaking economic elites out of zero-sum conflicts over who controlled which patch of farmland. Now you can get rich by building a better mousetrap, and you can get top intellectual status by running a better lab.

Conflict Theory as Moralism

When I introduce this paradigm in my classes, it tends to get a different reaction than the others. Students are usually more into it. As I describe Marxian theory, I notice people paying close attention, heads nodding in agreement. If it’s a really engaged class, I half expect to hear a shout of “Amen!”

This doesn’t happen when I talk about how suicide varies inversely with social integration, or how successful people have networks rich in structural holes.

You might think that, as an educator, I’d be glad for enthusiasm rather than the usual apathy. But I often feel a little bad about it, like a parent who let the kids have chocolate cake for supper.

It seems to me scientific thinking about human behavior comes with great difficulty to most people. But moralistic thinking — identifying enemies, choosing sides — comes easily and naturally. Read Frans de Waal’s Chimpanzee Politics (or this news item) for a sense of how deep-rooted such instincts are. The human animal readily divides the world into friends and enemies, good guys and bad guys.

I think the main reason conflict theories are so interesting and intuitive is that they tap into this tendency. Here you go, class: On this side, a domineering bully or spoiled rich kid we’re supposed to dislike. On the other, a sympathetic victim, maybe even one who shares your particular identity. Who are you going to root for: Darth Vader, or the plucky rebels? Now let’s analyze all the devious ways this bad guy keeps us good guys down.

I think it’s this aspect of conflict theories that accounts for their prominence, not just in modern sociology, but in many other institutions.

It also accounts for why work in this paradigm is rarely scientific, even by the low standards of sociology. For conflict theories — especially the fashionable critical theories of the past decade — are the go-to for activists and radicals. As Badley Campbell and I wrote elsewhere: "Most conflict theorists do not present their work as value-free or as scientific in any sense . . . in practice the framework acts almost exclusively as a moral and political ideology rather than a sociological theory.” It’s a paradigm that attracts those who are less interested in science than in politics.

This isn’t necessarily just true of leftists. True, conflict theories that come out of the academy focus on the favorite good guys and bad guys of the political left. But outside academia, one can find rightists making similar arguments. This seems especially so in recent years, with narratives about how society is slanted in favor of the professional-managerial class, the deracinated globalists, and the Deep State bureaucrats.

I would even characterize neoreactionary writer Mencius Moldbug (now writing on substack under the name Curtis Yarvin) as the right-wing Marx. He too has a grand account of society — one in which virtually everything is organized toward advancing the power of the left-wing oligarchy. Democratic institutions serve to obscure and strengthen this oligarchy. The ruling ideas are those of the ruling class, and they serve to invert reality and facilitate power. Normal attempts to combat this through electoral politics and activism are actually counterproductive, only strengthening a left-wing Leviathan: “Cthulhu may swim slowly. But he only swims left.” It will take revolutionary change — a return to monarchy, a modern Augustus — to end the power of the leftist oligarchs.

The rightist version has the same attractions and problems as the leftist one. Both appear descriptively accurate about various things: “Wow, those mine operators and railroad tycoons really did have a lot of sway”; “Yeah, it does seem like all the academics and journalists parrot one another.” But at the end of the day neither explains much variation.

Conflict Theory as Science

I return to the questions I asked in the introduction: Does this paradigm have anything to offer the study of social life?

The conflict paradigm is like the rational choice paradigm in assuming a selfish pursuit of interest. But it focuses only on zero-sum clashes and so is best suited to arenas of social life where this assumption actually holds.

Ironically, this means conflict accounts are badly suited to Karl Marx’s chosen field of economics. For the supply of material wealth — food, shelter, clothing, machines — is not fixed. People steeped in conflict theory have trouble even recognizing this (seriously, try to explain wealth creation to a young sociologist sometime). But they might correctly intuit even if wealth as such is not fixed, elite status is. And conflict theorists do better when they focus on positional goods like high fashion or the fancy degrees, which are valuable to the extent the hoi poloi don’t have them.

The term zero-sum comes out of rational choice game theory, so it’s not as if conflict theorists are unique in paying attention to such things. What else does the conflict paradigm do differently?

Game theories focus on individuals or firms as discrete decision makers. Conflict theory is like functionalism in its focus on broad collectivities, such as social classes. This carries with it the same potential downsides of reifying groups. Functionalists can be cavalier in talking about society wanting or needing something, as if it were a singular being. And at their worst, conflict theorists will speak of classes in the same way, with discussions that take on an almost conspiratorial tone — as if all the men, whites, or capitalists in the world held a weekly meeting to decide on the next directions for their dastardly plan.

And yet . . . when we discussed functionalism, we noted that human cultures do have traditions that are crucial for their survival, such as techniques of food preparation that leach out poisons. And people might follow these traditions without remotely understanding their importance — just doing them because they’re the done thing.

It’s not too big a stretch to think that social practices might likewise arise that help some subgroup in society gain more wealth or status or have lower infant mortality or whatever. These things might even be opaque to all involved. The question of hidden benefits isn’t inherently illegitimate.

But I think the question is best investigated by looking at clearly defined outcomes, and by actually taking it as a question — instead of assuming that elites always have the advantage in any and all things. And one should be wary of conspiracy-theorizing that there’s hidden exploitation in everything: symbolic violence in the peanut butter, hegemonic whiteness in the jelly.

Sociologists will sometimes say the conflict approach is useful for understanding social inequality. It certainly sensitizes one to the effects of inequality as an independent variable. Then again, human beings are already greatly concerned about social status, so it’s not hard to be sensitized to it. And conflict theories sometimes lead to what Donald Black called monotheorism, in which all social life is explained by a single variable: power.

But while few other approaches completely ignore power, perhaps it is good to have the reminder that, indeed, sometimes one side dictates the terms of the contract, and the other side has few alternatives. Oligarchies do emerge, and the average or aggregate preferences of some groups are more likely to find their way into law and policy. If this conflict theory or that feels at least descriptively accurate, it is because in various times and places, some animals are more equal than others.

Still, my sense is that the few conflict theorists who have done scientifically promising work have done it not because of their paradigm, but in spite of it. Some people gravitate toward relationships between variables, and don’t get distracted by morality tales. But for the modal thinker, the morality tale is a powerful attraction, and so the conflict paradigm is a slippery slope.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, you can leave a one-time tip at this Stripe link. Change the default amount to anything. Or become a subscriber with the button below.