This is part 8 in a series on how sociology and related fields explain human behavior. It’s based on a course I teach, which is adapted from a course I took from sociologist Donald Black at the University of Virginia. Part 1 through Part 6 talk about the general nature of explanation and how to judge one. From Part 7 onward we cover different strategies of explanation, or paradigms, found in the social sciences.

In this installment we cover the motivational paradigm. As sociologist Donald Black defines them, motivational theories explain behavior with the psychological impact of social forces.

This paradigm is a little different from the others, in that it’s a category I think is unique to Black’s scheme for classifying strategies of explanation. Mention categories like phenomenology or rational choice theory to any sociologist, and they’ll more or less understand what you mean. Mention motivational theories and they probably won’t.

I think this is partly because Black has put a name to what is for most people a residual category: Just normal sociology and social psychology that doesn’t fit into some other recognized school of thought. Though they might be more likely to recognize some of his subtypes, such as strain or learning theories.

But before we get into that detail, let’s illustrate the paradigm with an example.

Say You Want a Revolution

Why do revolutions happen? One strategy for answering this question is to ask what makes people decide to rebel against their rulers.

When he forecast the great revolution of workers against owners, Karl Marx implied that people rebel because they have been made poor. For Marx’s vision of the future of capitalism was a world in which workers were made steadily poorer and more miserable, living on the cusp of subsistence.

You can check some American obesity statistics for the accuracy of that projection, but the idea that immiseration leads to rebellion is intuitive enough. Yet French aristocrat and astute observer Alexis de Tocqueville argued that the lower classes were immiserated for most of history, and their usual reaction was just to focus on getting their next meal. Great upheavals like the French Revolution occurred when people were generally better off than they’d been in the past, giving them the breathing room to worry about grander plans and aspirations beyond surviving the winter.

Sociologist James Davies aims for a synthesis of these ideas in his theory of revolution. He argues that people rebel primarily because they expect better than what they are getting: They have hopes of an improved world, and these expectations are frustrated by reality. But what circumstances could lead to such frustration?

A steady state of poverty or oppression won’t do it. Over a long enough time period that just becomes normal and taken-for-granted. Plus, as de Tocqueville pointed out, if things are harsh enough people’s energy mostly goes toward making it to the next day or season.

A long, slow, steady decline wouldn’t do it either. Sure, things are getting worse, but if it’s slow and steady enough, the frog might not notice he’s being boiled.

And if things are getting steadily better — what’s frustrating about that? Just hang tight and await good times to come.

The thing that motivates people to rebel, said Davies, is when you get this: A prolonged period of improvement in the economic or social conditions, followed by a sharp reversal.

The period of improvement might include things like rising wealth and living standards or greater political freedoms. In any case, things get better for a while. This creates higher expectations among the populace. A new and better world seems possible. Poverty, oppression, and the like stop being just normal.

Then comes the reversal. The economy tanks or the authorities crack the whip. The degree of reversal might be such that the conditions are still better than they were 10 or 15 or 20 years prior — but that’s not people’s point of reference anymore. The period of improvement gave them greater expectations, and now those expectations are dashed. This frustration that gives rise to rebellion and revolution.

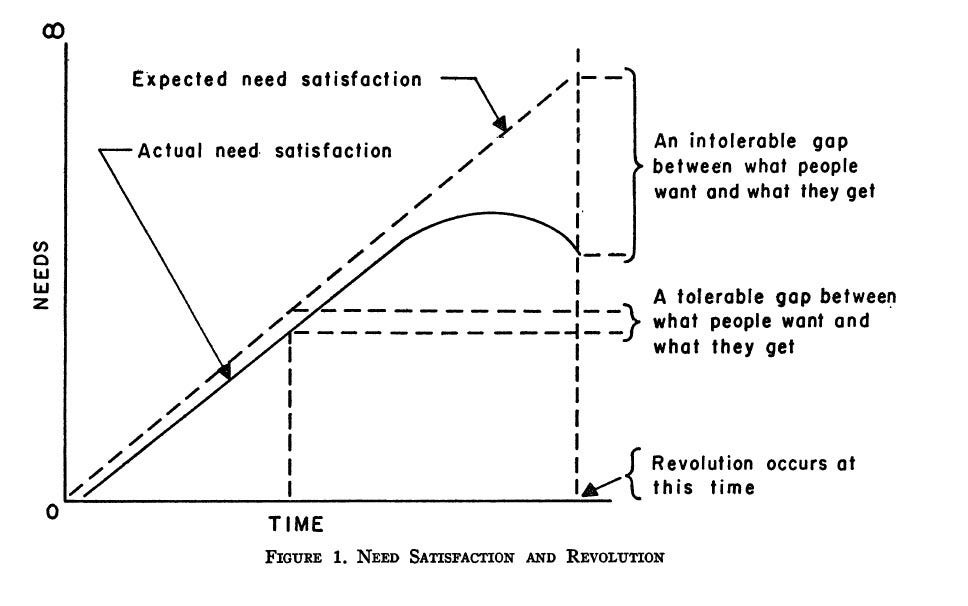

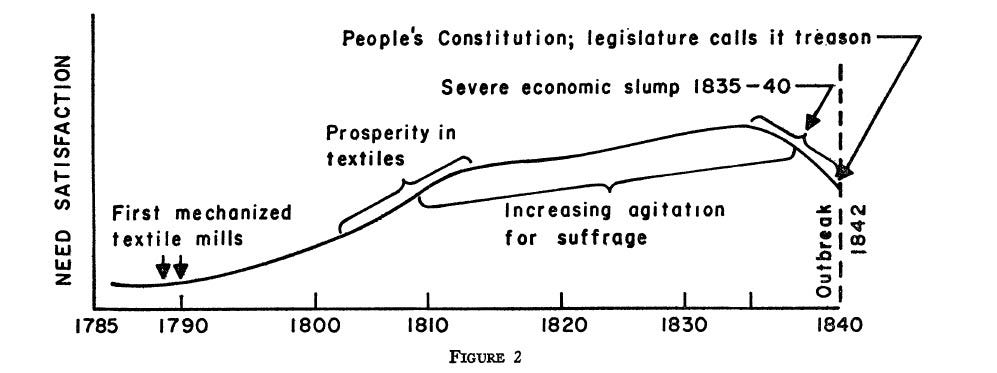

The theory is known as Davies’s theory of revolution, or sometimes the J-curve theory of revolution, since if one were to graph these social and economic conditions leading up to revolution it would look like a letter J turned on its side. Things get better, then there’s a sudden downturn: That is when people are most frustrated and apt to rebel.

The Motivational Paradigm

This example illustrates the key features of the motivational paradigm. One explains a behavior (revolution) with a psychological state (frustration over the clash between expectation and reality) arising from social factors (improving economic conditions followed by a downturn).

That is, when one sees a behavior — rebellion, crime, or suicide — one asks what on earth would make a person want to do that.

Note that this sort of explanation assumes the person actually can rebel or commit crime or suicide. As Black puts it, such theories assume opportunity and explain motivation.

In our last installment, we considered phenomenological theories, which explain by asking what mental state makes a person behave that way. Motivational theories go a step beyond and ask what external factors cause those mental states to come about. Here the mind is relegated to an intervening variable, something that is itself the outcome of social forces. This strategy is, as Back notes, deterministic: Your decisions are predictable with influences outside yourself.

But still the strategy has an individualistic component. For instance, Davies’s theory involves thinking through what impact broad social and economic trends have on individual people’s expectations and frustrations. As sociologist Talcott Parsons wrote in The Social System, “It is a cardinal principle of the present analysis that all motivational processes are processes in the personalities of individual actors.”

Both Parsons and Robert Merton wrote about the importance of motivating factors in human society and how one can explain conduct with forces that impelled individuals to pursue one behavior or another. Their discussions may have influenced Black’s choice of the label “motivational theory,” though as far as I know he’s the only one to have defined it as a distinctive paradigm amid all the other kinds of sociological explanation. And he further subdivides it into four types, defined by the source of the motivation.

Strain Theories

In strain theories, social forces produce frustration, and the frustration then produces the behavior. Davies’s theory of revolution is one example of a strain explanation.

Another example would be Robert Merton’s strain explanation of deviance (often known as “structural strain theory”). In his paper “Social Structure and Anomie,” Merton says is aim is to show how certain social structures put pressure on individuals to engage in conformist or nonconformist conduct. Two major features of society are relevant: Cultural goals and institutionalized means.

Cultural goals are whatever a society generally holds up as ends worth pursuing: Financial success, having lots of kids, carrying out jihad, or whatever.

Institutionalized means are the society’s approved and legitimate ways of pursuing those goals. Yes, make money — by starting an honest business, not by gambling or stealing or conquering Gaul for loot and slaves.

Complete conformity happens when people accept both the cultural goals and institutionalized means. They’re pursuing what they should, the way they should. Various kinds of deviance come when they reject either goals, means, or both.

Accepting goals but rejecting the means he calls innovation. I suppose this is meant to be a value-neutral term that includes deviant means that might later be appreciated and normalized. But in the article, he mostly talks about becoming successful through crime, like robbing or bootlegging, and that’s mostly what people concerned with using this theory focus on.

(His other categories of deviance are the empty ritualism of the bureaucrat who has abandoned the goals but sticks to the means and the retreatism of the hobo who gives up on both goals and means. These tend to get less attention, so let’s focus on his explanation of crime.)

One idea Merton had was that people’s access to the institutionalized means varies according to their place in society. If someone, due to their class or ethnicity or whatever, has less access to the legitimate means, they’re more likely to reject them. Assuming they’re have the same socialization toward cultural goals, they’ll be more likely to turn to crime to achieve them.

This is Merton’s theory of why immigrants formed criminal gangs in the early 20th century. He assumes immigrants and natives all buy into a variant of the American Dream of economic success. Poor, not well-versed in the language or well-connected to the successful, first-generation immigrants in the Italian enclave didn’t have the same access to legitimate means. Rather than give up the goals, they turn to robbery and the numbers racket and bootlegging. It’s basically a theory of Al Capone.

While this surely isn’t the origin of the popular idea that poverty and lack of opportunity cause crime, it might be the trope codifier in sociology and criminology.

Notably, it would seem to mostly apply to acquisitive crimes, such as predation (like robbery) or illicit business (like bootlegging). It wouldn’t necessarily explain why domestic violence or hot-blooded killing over trivial arguments varies across neighborhoods or demographic categories.

There is some statistical evidence that property crime rates go up during bad economic times, lending support to the idea that when access to legitimate means falls, use of illegitimate ones grows. But even if it’s real, the relationship isn’t strong enough that other factors can’t overwhelm it: There’s periods where crime rises despite the growth of legitimate opportunities or continues falling despite hard times.

In criminology, Merton’s structural strain theory was a precursor to Robert Agnew’s general strain theory, which has similar logic (social experience leads to frustration leads to crime) but recognizes that sources of frustration are many and situational. I suspect that what it gains in generality it loses in predictive power, but it’s led to a cottage industry of research that you can search at your leisure.

Learning Theories

In learning theories, we explain behavior with some socialization process that creates the psychological disposition for the behavior.

For instance, criminologist Ronald Akers proposed a social learning theory of crime with two main variables: Differential association and differential reinforcement. Regarding association, people are likely to become criminal to the extent that they associate more with criminals and less with noncriminals. In addition to facilitating direct imitation, this encourages people to learn particular attitudes and beliefs supportive of crime (“Hey, they have insurance, it’s fine”). Regarding reinforcement, people are more likely to become criminal to the extent criminal behavior is rewarded more than noncriminal behavior. Your thief friends show you how to steal, teach you that stealing is okay, you learn from experience that it pays when you get away with your initial thefts, and thus you become a person with an inclination to regularly steal.

In an earlier installment, we distinguished a true explanation from an orienting statement that tells broadly how to go about explaining things. To count as a learning explanation, one can’t simply say that people do X or Y because they learned them — one must specify some variable that makes a person more likely to learn X rather than Y.

One might also posit stages in the learning process, with the theory being that completing one stage is necessary for completing the next, and that completing the process is necessary for engaging in the behavior.

For example, in sociologist Howard Becker’s “Becoming a Marihuana User,” he argued that the motivation to smoke marijuana for recreation actually comes after initial use of the drug. This is because to become a regular user, one must first learn the technique to smoke correctly so as to get high — many don’t get high the first time they try smoking weed. Then one must learn to recognize the sensation of being high — many people high for the first time are unaware that they are. Then must learn to enjoy the sensation — some find it scary or unpleasant at first but acquire the taste with practice. Only by mastering each of these steps will a person become someone who wants to smoke a lot of marijuana.

And one can combine strain and learning approaches, proposing that both frustration and socialization together lead to an outcome. In his theory of why people become violent dangerous criminals, criminologist Lonnie Athens proposes a four-stage process involving both strain and learning factors. Violent subjugation at the hands of others, plus the horror of seeing loved ones victimized, creates great psychological pressure to avoid being a victim. Meanwhile, having significant others encourage and glorify violence makes it more likely that a person will resolve to use violence to solve the problem. If the person’s first violent performance results in a socially significant victory — say, they gain a reputation as a badass, and come to enjoy this status — they’ll likely become someone inclined to use severe violence at little provocation.

Bonding Theories

In bonding theories, the motivation or disposition for a behavior comes from the presence or absence of social bonds.

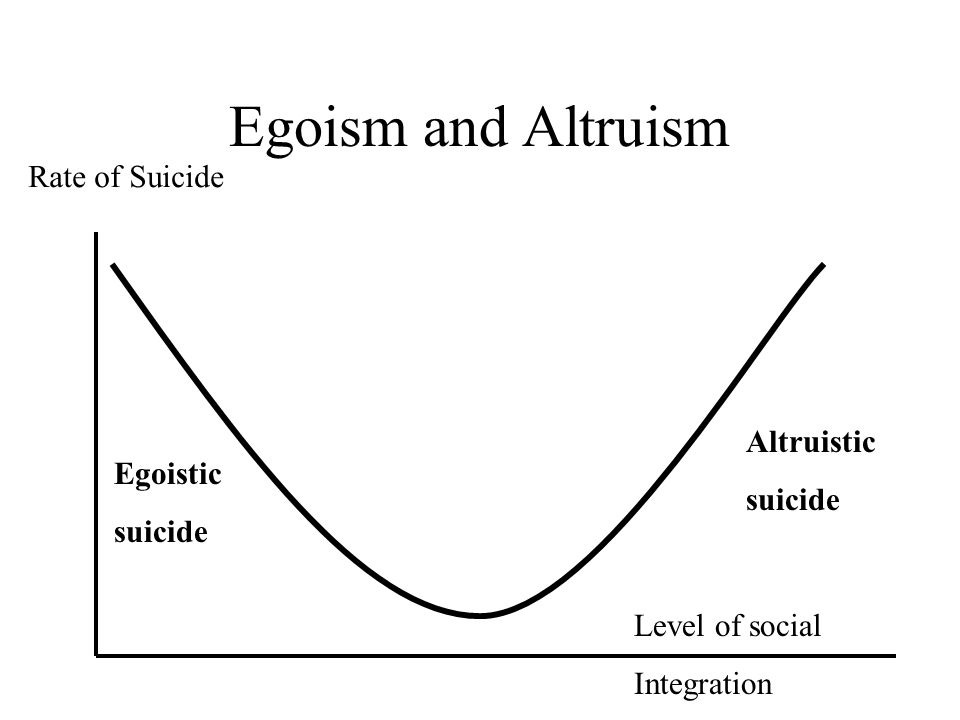

A classic example is early sociologist Emile Durkheim’s theory of egoistic and altruistic suicide. This theory focused on the role of social integration — of social attachments and involvements — in making suicide more or less likely. Durkheim argued that when social integration is too low — when people lack participation in social relationships and institutions — they are more likely to kill themselves. This happens in part because people need to be committed to something larger than themselves to endure all of life’s trials — as he puts it, “the individual alone is not a sufficient end for his activities.” He also argues that being socially detached itself is a source of suicidal motivation, something that inclines people to do away with themselves. He called suicide arising from too little integration egoistic suicide, since it came from too much individualism.

On the other hand, he argued, when social integration is too high — when people were too densely networked, and not individualistic enough — they again become more likely to kill themselves. This is because with too much integration, the individual loses his value relative to the collectivity. Such individuals are quick to sacrifice themselves on behalf of the group. In the extreme, the entire group might be motivated to destroy itself to achieve some higher purpose, as in the mass suicide of a religious cult. He referred to such suicides as altruistic, since they were concerned with upholding group norms.

Combining the two theories, the relationship between social integration and suicide is U-curvilinear: Both too few and too many bonds lead to increased suicide.

Note again this is a theory of motivation — of what makes people seek to kill themselves. One might also explain suicide with what allows the suicidal to act on their inclinations, such as with the distribution of relatively easy and foolproof methods like guns or coal gas.

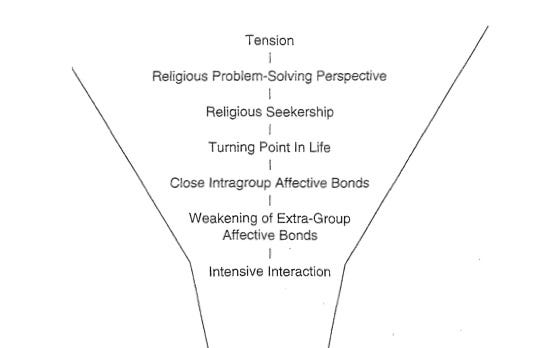

And just like the same theory might combine elements of strain and learning, so too might a theory combine elements of strain and bonding. For example, in their article “Becoming a World Saver,” sociologists John Lofland and Rodney Stark explain why a person would convert to a “deviant perspective” — in other words, why they would join a cult.

The theory is based on their observations of the Unification Church of Reverand Sun Yun Moon, a sect popularly known in America as the Moonies. Lofland and Stark had the good fortune to become acquainted with the cult’s first American converts early on in their process of conversion, and so were able to get detailed information on the process. They propose that to go from a non-member to a “total convert” who puts their life in the hands of the group requires a series of steps.

The first of these is a strain factor: The potential convert must be in a state of tension, full of frustration between what their life is like and what they wish it to be. If the person then acquires (or perhaps already had) a tendency to seek religious solutions to problems, they then become a religious seeker. Most converts when through a period of actively searching for religious or spiritual solutions, and in fact several had a history of hopping from sect to sect in search of the right answer.

Another shared feature of converts is that they encountered the cult at a turning point in their lives — a time up change such as moving to a new city, losing a job, or losing a marriage. They then formed some sort of bond with cult members. The bonding is a key feature: Those who encountered the cult and its message without making some sort of friendship with cult members never came around to believing in the cult’s doctrine.

Also key is lacking or ending bonds outside of the cult. Converts tended to start off as loners, and if they weren’t they needed to sever competing ties before fully converting. Those who kept close ties outside of the group were likely to be convinced by these outsiders to give up their involvement with the cult before they could come to accept the cult’s beliefs.

In the end, joining the group mostly meant coming to accept the beliefs of their friends, and so conversion depending on having more friends in than out. And the more intensely they socialized with their new friends, the more committed they became to the new beliefs.

One interesting aspect of this process was that converts tended to rewrite their history: If asked, they would explain that they were drawn to the cult by its beliefs, and then made friends with its members. The opposite is true: Many were openly skeptical of the cult’s beliefs and came to endorse them only after members became their friends.

Compliance Theories

Compliance theories, according to Black, explain behavior as the direct result of interpersonal pressure. Explanations that appeal to a pressure to conform to the group or to obey authority use this strategy.

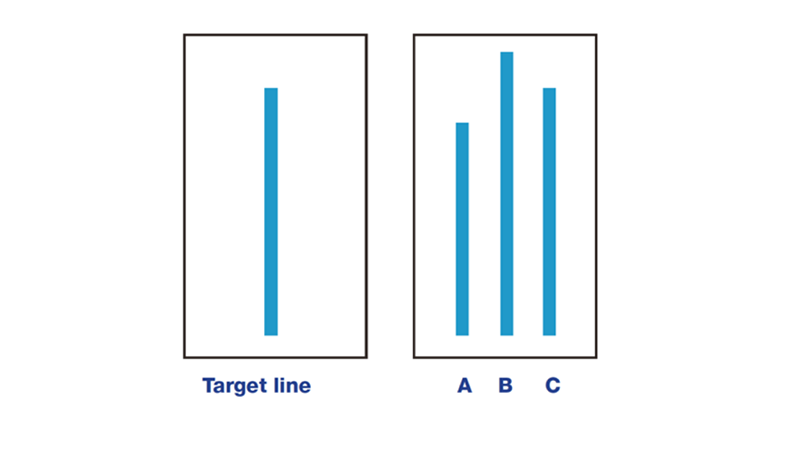

One well known example is social psychologist Solomon Asch’s work on conformity. His ideas came from a series of experiments in which he showed subjects an image with a line, and then another image with three lines, only one of which was the same length as the first. He then asked subjects to choose the one that was the same length.

He ran this experiment with batches of eight subjects, who would take turns giving their answer. The trick was that only one of the subjects was real, and the rest were confederates of the experimenter. These confederates gave accurate answers on the first two trials, but on the third they had been instructed to pick the obviously wrong answer.

You can find a video of the experiment on Youtube.

Asch found that up to a third of the subjects went along with the group in giving the wrong answer, despite it being quite obviously wrong. In debriefing interviews, some said they knew it was the wrong answer, but didn’t want to make waves. Others reported doubting the evidence of their own eyes and thinking the group really must be correct. Some of the subjects who stuck to their guns and gave the correct answer later reported feeling enormous pressure to go with the group, and great relief when the experimenter revealed the nature of the experiment to them.

Notably, Asch investigated variables that affected the degree of conformity, and found that much of the group’s power over the individual came from its unanimity: When a single confederate was instructed to break ranks and give the correct answer, the rate at which subjects conformed to the majority plummeted.

Pressure to conform can lead to extreme behavior outside of the laboratory. In historian Christopher Browning’s book Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, the author asks what led a group of middle-aged German police reservists — who were neither psychopaths nor Nazi fanatics — to carry out mass executions of Jews.

His main answer is both the pressure to obey authority and the pressure to conform to the group. As long as a critical mass of the men were willing to go along with the orders, their fellows were not willing to break ranks and even implicitly criticize their friends’ conduct by refusing to take part. The few who did actually refuse criticized themselves as too weak, casting their refusal as a personal failing rather than defiance of the group. And perhaps, to them, it was.

I started this installment by noting that of all the paradigms classified by Black, this is the most unique to his scheme. And since it lumps together approaches that others might prefer to split, it’s arguable whether the overall category of motivational theory makes much sense.

I think it makes somewhat more sense in reference to two other categories we’ll cover in this series. One is Black’s own paradigm, which avoids talking about psychological mechanisms altogether, and takes its fundamental unit of analysis as something other than the individual actor. The other is the approach we’ll consider in the next installment: Part 9: Opportunity theories.

See also Part 8.5 for classroom exercises on applying and evaluating the theories discussed in this post and the last, as well as on getting students to brainstorm their own theories using these paradigms.

As always, thanks for reading! And special thanks to the paid subscribers! Leave a comment if you have insights, questions, or requests.

If you aren’t a subscriber, consider becoming one at the link below. Free subscribers will never miss a post, and paid subscribers get access to archived posts and special content. If you like this sort of thing, you can also support Bullfish Hole by leaving a one-time tip with Stripe or Paypal.