This is part 9 in a series on how to explain human behavior. It is based on a course the late Donald Black taught at the University of Virginia. Parts 1 through 6 discussed the general logic of explanations and how to test them. From Part 7 onward we cover different strategies or paradigms for developing explanations.

In the last installment we addressed motivational theories. These explain behavior by specifying which social force acts on the individual to motivate that particular conduct. For instance, Robert Merton’s classic strain theory of crime posits that in a culture where people place a strong value on wealth, those who lack access to legitimate means of gaining it will become frustrated. Their way of dealing with this will be to turn away from the legitimate means and toward criminal ones.

Writing in 1979, criminologists Lawrence Cohen and Marcus Felson pointed out that this theory, or something like it, couldn’t account for the crime trends of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Poverty and unemployment were down, education was up, the Civil Rights Movement had made great strides. There ought to have been fewer blocked avenues for success, and so fewer frustrated or desperate people turning to crime. Yet despite good economic times, crime still rose. Between 1960 and 1975, robbery was up 265 percent, and the burglary rate was up 200 percent!

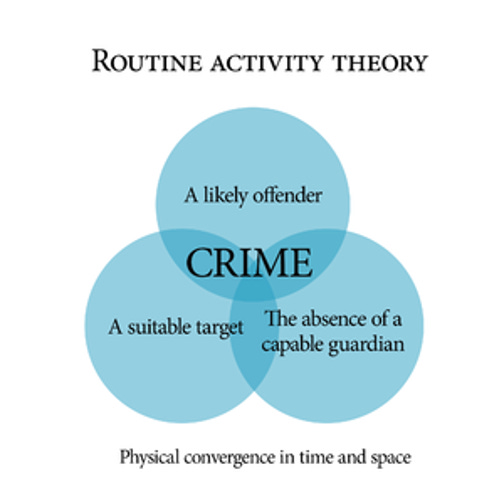

To explain this, they recognized that a motivated offender is only one ingredient in crime. If it’s a predatory crime, like robbery, they also need a suitable target — one can’t be a thief without something stealable to steal. And criminals need to be able to come across that target at a time when there’s no guardian capable of stopping them.

Since predatory crime requires all three factors — offender, target, and absence of guardians — crime rates aren’t just driven by conditions that motivate offenders. They’re also driven by conditions that give criminals more unguarded targets. The population of criminals can stay the same or even decline, but if there’s more opportunities for them to commit crime, the crime rate can still go up.

What are some trends in the late 1960s and 1970s that lent themselves to rising crime? Consider the increase in suitable targets for theft. Cohen and Felson note that a suitable target is something valuable, moveable, and transferable. As the nation got wealthier and as technology advanced a lot more people had valuable but lightweight electronic goods. Radios went from being bulky things that took up space in the living room to easily portable devices. Cars are big but you can drive them away, and more and more people had them.

…Burglary data for the District of Columbia in 1969….indicate that home entertainment items alone constituted nearly four times as many stolen items as clothing, food, drugs, liquor, and tobacco combined and nearly eight times as many stolen items as office supplies and equipment. In addition, 69% of national thefts classified in 1975…involve automobiles, their parts or accessories, and thefts from automobiles or thefts of bicycles.

Postwar prosperity meant people also had more cash, more jewelry, more fancy watches.

And what about guardians? We all guard our homes just by living in them — whether we would personally put up a fight or call the police or scream for the neighbors, being at home makes it difficult for a burglar to burgle. And one trend that took off in the 1960s and 1970s was people spending more time away from home. With the large-scale entry of women into the workforce it became far more common for houses to be unoccupied for large chunks of the day. Also, growing wealth and access to cars meant more long-distance travel, leaving houses unoccupied for days at a time. On the other hand, with more people working outside the home or travelling about, businesses tended to keep longer hours than before. They were informally guarded by employees and customers for more of the day.

The composition of crime reflects these changes. Between 1960 and 1975 the rate of residential burglaries doubled, while the rate of commercial burglaries fell.

Cohen and Felson thus argued that change in the amount and nature of crime is driven by change in the routine activities of the noncriminal population. This applies to the country as a whole, and also to particular cities or neighborhoods. The rate of armed robbery in a downtown area might spike simply because a bank installed a new ATM machine, giving robbers a place to encounter victims with cash. Robbery might decline again just because people shift to paying with cards and visit the ATM less.

Their insight became known as “routine activities theory.” While the basic idea might seem obvious enough in hindsight, the great innovation was in turning attention away from the motivating factors most people focus on when asked to identify causes of crime. Crime trends can be driven by things that have little to do with criminal inclinations, and a lot to do with criminal opportunities.

The Opportunity Paradigm

“Opportunity theory” is a concept coined by Donald Black, who saw it as a distinct strategy of explanation. Opportunity theories explain behavior with the distribution of factors that make it more or less possible.

These theories are in one sense the inverse of motivational theories. Motivational theories assume the ability to do something and try to explain the motivation. Opportunity theories assume the motivation to do something and try to explain the ability. For this reason, the two approaches can be complementary — an opportunity theory of crime, suicide, or whatever else can easily exist alongside a motivational theory of the same thing, because they each explain a different aspect of the behavior.

Cohen and Felson’s routine activities approach is an example of an opportunity explanation, in that it directs our attention to the factors that allow criminals to commit predatory crimes.

Another example is the work of sociologist Peter Blau, such as his book Inequality and Heterogeneity or his classic article “A Fable About Social Structure.” Blau thought systematically about how things like the size and diversity of subgroups effected their opportunities for contact, friendship formation, and the like.

For instance, in a country where 90 percent of people are white and 10 percent are black, it’s far likelier for blacks to encounter whites than for whites to encounter blacks. Even if we lived in a world with no race prejudice, you’d expect a lot of white people to not have black friends, just because there’s fewer opportunities to make them. On the other hand, it would be much more common for a black person to have a white friend. One shouldn’t jump to any conclusions about the relative prejudice of the groups (or other motivational factors) without accounting for the opportunity factors.

This effect of group size could also explain how, even with no particular pressure to assimilate, minorities still get absorbed into majorities. Given relatively free mixing, the pool of potential friends and spouses just includes more of the majority. The minority has more opportunities for exogamy.

Another place we see opportunity explanations is in the area of sociology that’s called network theory.

Networks of Opportunity

The modern study of social networks owes a lot to Harrison White, who migrated into sociology after completing a doctorate in physics. That background made him fluent in math, which he applied to his sociology. I am not fluent in math, so I can’t claim a deep understanding of his work. But, for example, one of his topics was vacancy chains in organizations.

To get a job at an organization requires a job be vacant. The same goes for getting promoted within the organization. People advance in their careers through chains of vacancies, and we can understand things like the speed and patterning of promotion with the properties of these vacancy chains.

For instance, a lot of organizations had a pyramidal structure, with fewer positions as one moves up the hierarchy. Many low-level workers, fewer middle managers, still fewer upper managers, one CEO. All else equal, fewer positions mean lower odds of any position having a vacancy. So the pace of promotions will tend to slow as one proceeds up the hierarchy. Workers who want to keep their promotion momentum will usually have to jump across organizations over their career.

White is the Socrates of sociological network theory and is as famous for his students as his own work. One of his students was Mark Granovetter, who followed his mentor in studying how people get their jobs. His focus, though, was on how job seekers found out about the jobs they succeeded in getting. Who gave them the useful lead? Mom? Dad? Favorite teacher? Best friend?

In his article “The Strength of Weak Ties,” he reports that useful leads tend to come from distant acquaintances — people that the job seekers don’t see on a regular basis. Often their lead came from someone they hadn’t seen in years but ran into by chance some place.

People are more likely to get jobs through their weak social ties, not their strong ones. We might view this as a sort of paradox — aren’t your strongest ties most motivated to help you? Likely true, but they’re not necessarily best positioned to do so.

Granovetter explains this with network structure. The closer you get to someone, the more your social networks come to overlap. A person’s closest friends and family will likely have all at least met one another, and probably see one another regularly. Often a person’s closest contacts form a circle or clique who spend more time with one another than with people outside the group.

The more your network overlaps with that of another person, the less likely you are to get new information from them. Since you tend to know the same people, you tend to know of the same opportunities. And if you don’t already know where to apply for a job, your strong ties probably can’t tell you.

Your weak ties, on the other hand, will tend to move in different circles than yourself. If they didn’t, you’d see them more regularly! The fact that your networks don’t overlap so much means that they’re likely to be aware of opportunities you haven’t heard about. Thus, a serendipitous conversation with a rarely seen acquaintance drastically expands your pool of information, making such weak ties important for locating job opportunities.

As Granovetter puts it, weak ties are more likely than strong ties to act as a bridge between different local networks. It’s the weak ties that stitch together the tight-knit groups of families and friends and immediate coworkers that make up society. And these bridging ties play a crucial role in disseminating information between these different regions of the social world.

All of which means it can be very advantageous to maintain a lot of these contacts outside your primary circle. Hence the title of his article: “The Strength of Weak Ties.” Social butterflies are apt to be in the know about a great many opportunities, from job openings to potential mates.

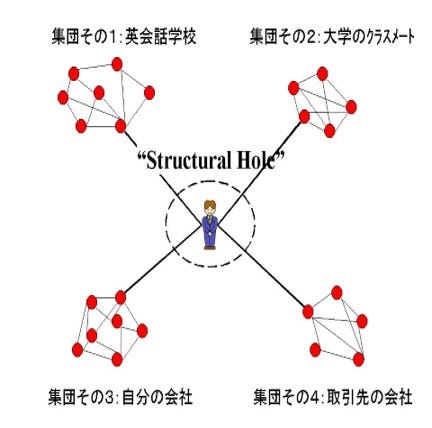

Ronald Burt extended Granovetter’s ideas with his book Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition.

In it, Burt reminds us that it’s not the weakness of the weak ties that brings advantage, but the fact that they bridge a structural hole between two networks that otherwise have no direct connection.

Indeed, the ideal social location for maximizing opportunity is a network rich in structural holes. Being connected to many otherwise disconnected networks gives one wide reach at low cost. It’s useful for gaining information, for getting referrals, and for getting both of those things in a timelier manner than your competition.

It also might allow you to control the flow of information — the middle of a structural hole is the social location of the broker, someone who can take a cut of the profits for putting buyers in touch with sellers. If they’re both sellers or both buyers, being their only mutual contact keeps them from colluding against you and lets you play them off against one another — “I’ve got a guy on the other line who will offer me double what you’re offering!”

In his book, Burt comes up with ways of measuring the amount of opportunity and constraint in different social networks and examines how this affects everything from the profitability of different economic sectors (real estate brokers in the individual housing market have it made!) to the pace of promotion for individuals within firms: People with insular networks stall, ambitious insiders benefit from their own extensive network, and outsiders benefit from glomming onto the preexisting network of a mentor or sponsor.

Here again, he’s not explaining what makes people seek profit or develop this kind of network or that. He’s showing how success follows the contours of opportunity inherent in different network structures.

Network theory and its opportunity logic have found wide application outside of sociology. For instance, all we’ve said about the spread of information through networks can also be said of the spread of disease.

It seems TED talks have a reputation for being pretentious, but this talk by Nicholas Christakis is pretty good (transcript included). He explains one way in which understanding networks and opportunity structures can help us better predict disease epidemics. If you can sample those highly connected social butterflies, they’ll be getting sick a few weeks before the masses, giving you some early warning that a wave of cases is coming.

The social butterfly has the advantage in looking for jobs and mates. But he’s the first to go when the plague comes to town. The network giveth and the network taketh away.

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole you can become a free or paid subscriber with the button below. Or if you’re not the type to commit, you can leave a tip at this Stripe link.