Topic Tags: Academia, Politics

In the fall of 2024, with support from Heterodox Academy, I did a survey of 327 graduate students at top US programs in physics, chemistry, biology, and psychology.

In a previous post, “Loud Liberals and Closet Conservatives,” I showed that liberals are a majority in all fields and reported more political interest and more political discussion. Conservatives, on the other hand, reported more self-censorship, less belonging, more perception of disrespect over their views, and more fear of professional consequences for their views.

We might then wonder if this has any effects on the career plans of conservative students in the sciences. There are certainly critics and commentators who say an academic environment hostile to conservatives tends to deter them from entering academia, creating an accelerating cycle of political homogenization. But to what extent does politics actually shape the careers in science?

We might start with asking about how politics shapes the decision to pursue graduate education in the first place.

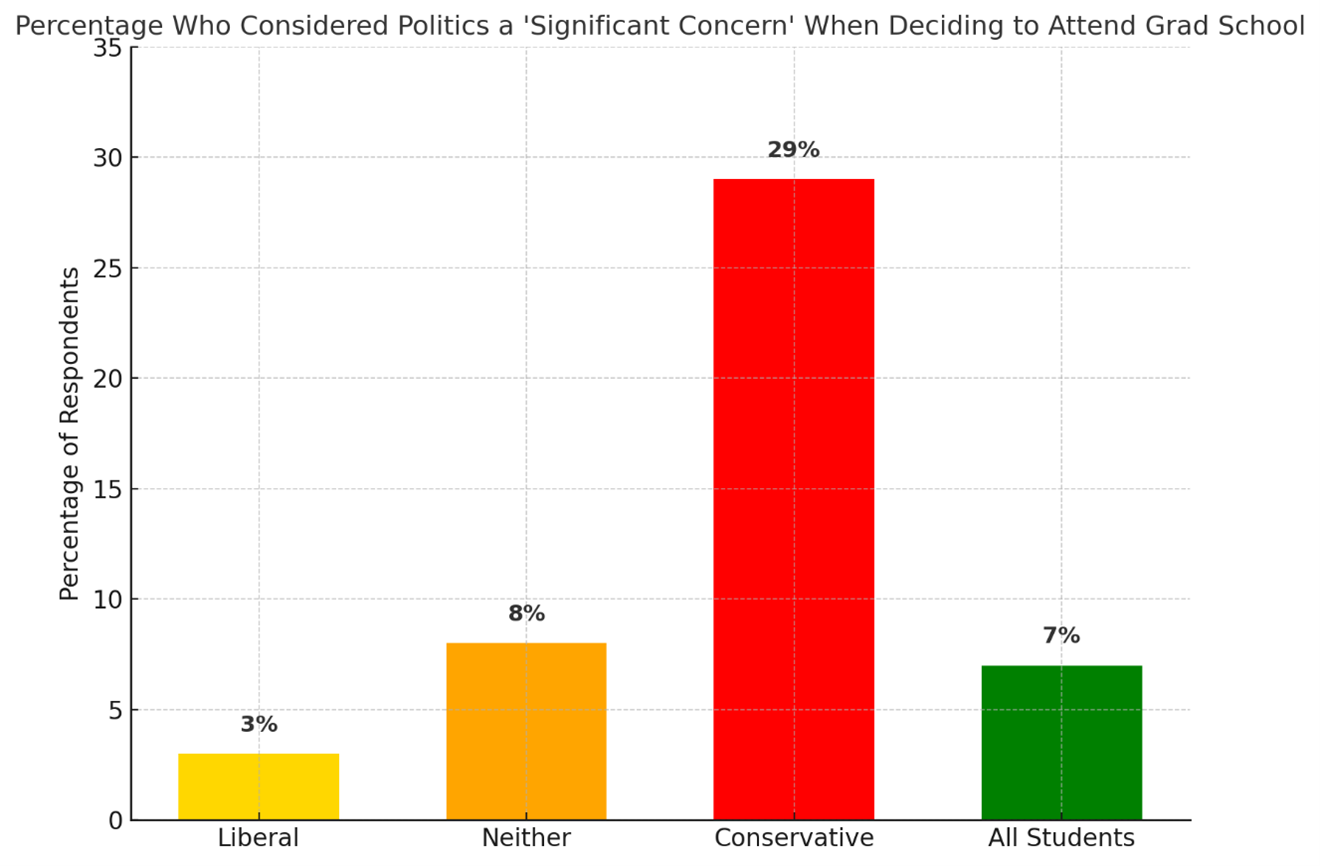

We asked respondents to choose from a list of potential concerns they might have had when considering whether to go to grad school, such as concern they would not find a job, or concern that they would not fit in because of various personal characteristics like race, gender, religion, or politics.

In the sample as a whole, only 7% considered not fitting in because of their politics a “significant concern,” a number comparable to concerns over race (7%), religion (7%), and gender (10%). As you might expect, this was a much bigger concern for conservative grad students than for liberal ones: 29% of conservatives were concerned they would not fit in because of their politics, as compared to only 3% of liberals.1

Our sample is restricted to those who ultimately went to grad school anyway, so it’s impossible to say what role political concerns played in the decisions of those who decided not to. But the fact that a third of those conservatives who did pursue graduate education weighed their political deviance when making the decision suggests that it is a factor, and that it would be worthwhile to find a comparison sample of undergrads who are considering grad school or college graduates who went with other options.

In the last post, we saw that conservative students in graduate programs were less likely to have a strong sense of belonging to their academic community and reported fear that expressing their beliefs could result in negative career consequences. One might think that harboring such beliefs would have some influence on career plans. Perhaps, viewing academia as a hostile environment, conservative grad students would be more likely to pursue employment outside of academia.

This does not appear to be the case.

We asked the grad students to rate several statements about career plans on a scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Overall, there was little consistent difference in career plans across different political identities. For instance, 39% of liberals and 31% of conservatives either agreed or strongly agreed that they planned to pursue a tenure-track job that emphasized research, while 24% and 26%, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that they planned to pursue a tenure-track job that emphasized teaching.

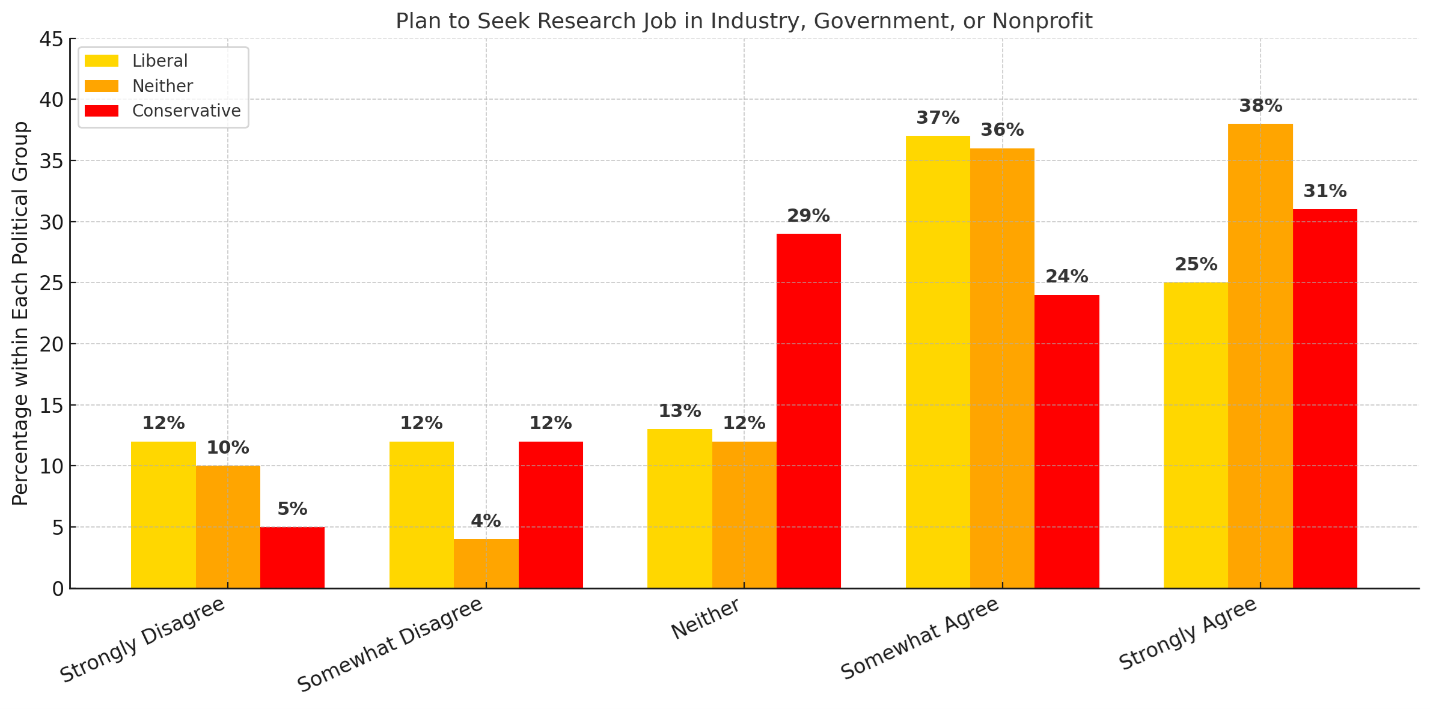

Regarding plans to leave academia altogether and pursue a research job in industry, government, or nonprofits, there isn’t a big or consistent difference. If you look at the extremes in the chart below — strongly agree and strongly disagree — it does look like conservative students are more inclined than liberal students to plan for research careers outside the academy. But there’s also a higher percentage of liberals in the agree category, and twice as many conservatives as liberals are on the fence. And none of this is statistically significant.2

To check my eyeballing of it, I dropped the “neither conservative nor liberal” respondents and did a comparison of just liberals and conservatives. The correlation (gamma) was .05, which is basically nothing.

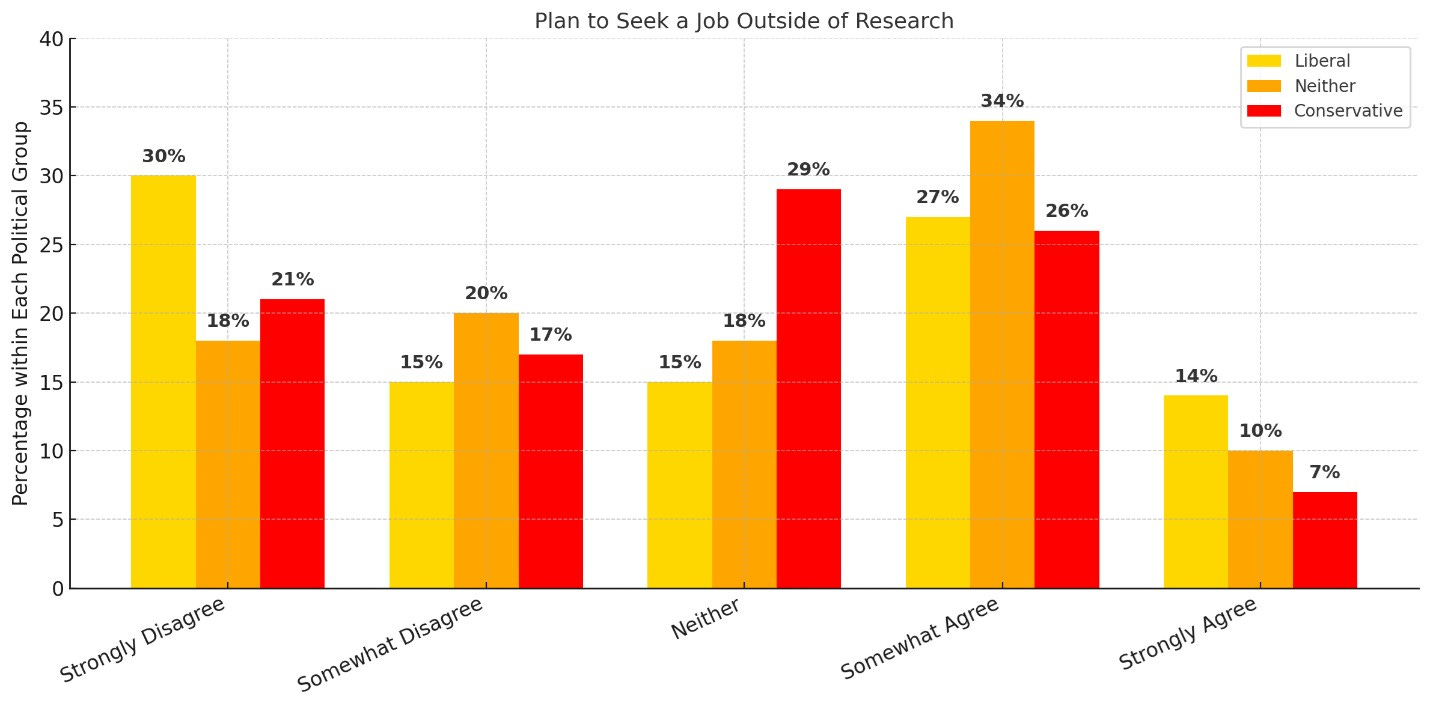

If we look at their plans to have a job unconnected to research, the results point in the same direction, with no consistent or statistically significant difference across political identities.3

I think the most you can say from this is that conservatives might be slightly more inclined to keep their options open, but they’re mostly still planning on the same tenure-track academic jobs as everyone else.

(Whether that’s realistic for anyone, regardless of politics, is another question.)

One might be able to get a signal in a larger sample, but our evidence doesn’t make me expect anything substantively large. Which is kind of puzzling, given the attitudes conservatives express about career hazards and such.

Maybe it’s something akin to the finding that people will be more pessimistic about the economy in general than about their own economic situation.

It could be related to how people see the general versus the particular, or near-mode versus far-mode. There’s a difference between a perception of academia as generally inhospitable and a perception of one’s own personal prospects. Thus “liberals don’t respect us” exists alongside “Barry is cool with me” — and Barry is the one you’re depending on for a rec letter, not “liberals.”

There’s also the possibility that, since they’re self-censoring already, conservative students think they’ll be fine as long as they keep their heads down and avoid trouble. “Yes, I think I’d face career setbacks IF I expressed my views, but I keep my mouth shut and focus on work and all is well.”

It could also be related to a tendency to be confident — maybe overconfident — about oneself, especially in the arrogant season of youth. Sure, they might think, it’s hard for conservatives in academia, but someone of my talents will make it just fine.

(Hey, I thought I was the bee’s knees at 23. It happens.)

Maybe their far-mode thinking is unduly paranoid. Maybe their personal plans are unduly optimistic. Maybe a little of both. Our cross-sectional survey of grad students can’t give us much information about what happens at later phases of the career process.

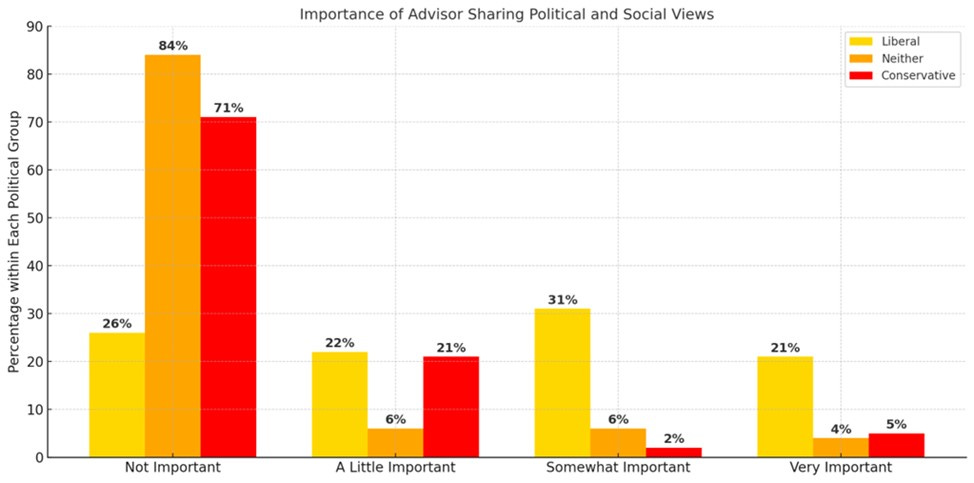

We do have some evidence that conservative professors would have more trouble attracting graduate students — something important for success in most academic careers. Consistent with their greater interest in politics, our liberal respondents were more likely to report a preference for ideological alignment with their faculty advisor. Asked to rate how important it was to have a faculty advisor who shared their political and social views, 21% of liberal students said it was very important, compared to just 5% of conservative students and 4% of students who identified as neither liberal nor conservative. Another 31% of liberal students said political alignment with their advisor was “somewhat important,” compared to 2% of conservatives and 6% who were neither.4

We don’t know to what extent this translates into action or what effect it has on faculty, but our finding suggests it is something to look into.

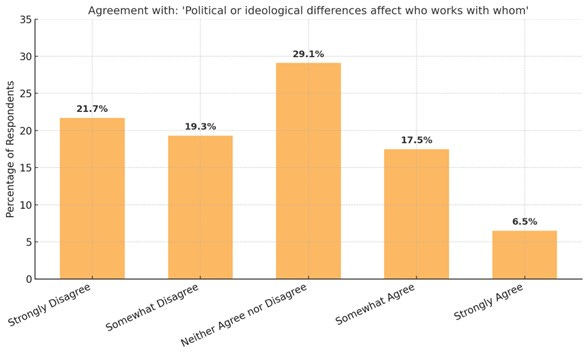

Also, across all fields, about a quarter of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that political and ideological views shaped patterns of collaboration in their department. Again, we don’t the behavioral reality — maybe the people who disagreed are closer to correct, or maybe they’re just unaware of what’s going on. But this is another plausible mechanism through which political conflict can shape academic careers.

In sum, our findings indicate that if the liberal skew of academia does not deter conservative graduate students from planning academic careers in science, but that it could deter conservative students from pursuing graduate training in the first place.

Given that the ideological tilt of academia is no secret, it seems likely to me that anyone who decides to pursue graduate education in the sciences is likely to have made their peace with it. If there’s a deterrent effect, it’s upstream.

Whether or not political bias has impacts later in their careers is a question for other research, but our findings suggest that effects on collaboration is one place to look.

n=327; chi-square=38.59; df=2; p=0.000.

n=327; chi-square=15.41; df=8; p=0.052. Close enough to p-hack, I guess, but I think if there were something really there it’d show up more clearly in the percentages.

n=327; chi-square=9.39; df=8; p=0.311.

n=327; chi-square=82.19; df=6; p=0.000.