A recurring theme in my monthly roundups are items on the sorry state of academia. One of many concerns is with how politicized and politically homogeneous various fields have become. I reckon my regular readers are familiar with the idea that undergrads in many fields are more likely to meet a Marxist than a conservative, or with surveys showing political bias in hiring and fear and self-censorship by conservatives or liberals with taboo ideas.

The issue looms largest in the social sciences and humanities, where political and ideological commitments directly influence research. But it might be an issue in the hard sciences as well. While there’s no obvious “conservative” or “liberal” positions on string theory, people who are homogeneous in one realm of thought might be inclined to homogeneity on other realms as well. The bigger danger, I suspect, is that the public and elected officials are likely to turn against academic science in general if they come to perceive that half or more of the political spectrum isn’t welcome in the university.

These sorts of problems are the reason for Heterodox Academy and its mission to promote ideological diversity and free inquiry in academia. Thanks to a grant from Heterodox Academy’s Open Inquiry in STEM program, I conducted a survey in late 2024 that looked into issues of political bias and politicization among graduate students in four scientific fields.

The Survey

I based my methodology on Christopher Scheitle’s study The Faithful Scientist, which looks at experiences of religious discrimination among grad students. Graduate training is a crucial phase in academic careers, when disciplinary identities are formed and career plans are made. If an increasingly politicized and political homogeneous environment is deterring conservatives from entering academia, this is an important place to look.

My grad assistant Drew Stover helped me randomly sample from the top 120 departments in physics, chemistry, biology, and psychology, picking 9 from each discipline. The idea was to get a range from physical science to life science to human science (psychology itself runs a gamut from relatively hard, neuroscience-based stuff to fluffy areas of social psych). For each department we constructed list of their current graduate students (about 3,000 altogether), who we then contacted to take an online survey with Qualtrics. The survey asked their professional identity and plans, as well as their political identity and experiences of interpersonal conflict and political discrimination.

We ran the survey from October 15 to November 7, 2024. With a response rate of around 11%, we wound up with a sample of 327 grad students. It’s too small for some of the subgroup comparisons I’d have liked to make, but it’s enough to get a broad picture of how politics crops up in top science programs. There are some interesting findings about conflict and career plans, but for this post I’ll just stick to describing the political leanings and political expression of the grad students.

Political Identity and Interest

15% of the sampled students were in physics, 42% in chemistry (they have huge departments!), 19% in biology, and 23% in psychology. There was a lot of demographic diversity: 55% were female, 50% were non-white, and 36% were not US citizens.

But there wasn’t much political diversity: Asked to rate themselves on a scale of very liberal to very conservative, only 14% chose any level of conservative, whereas 71% chose some kind of liberal and 15% identified as neither.

More students described themselves as “very liberal” (25%) than described themselves as in any way conservative, and only 1% of students described themselves as “very conservative.”

Prior research finds the liberal skew greater in the social sciences and humanities, and in our sample too psychology was the most liberal of the four fields, with 82% of respondents identifying as liberal, compared to 72% of physics and 67% of both biology and chemistry. These aren’t huge differences though, and there’s a liberal supermajority among grad students whether they’re in physical science, life science, or human science.

Political identification might be an abstract thing with little consequence, or it might be an important part of people’s lives. We can measure the latter by asking people about their degree of interest in politics and how often they discuss politics.

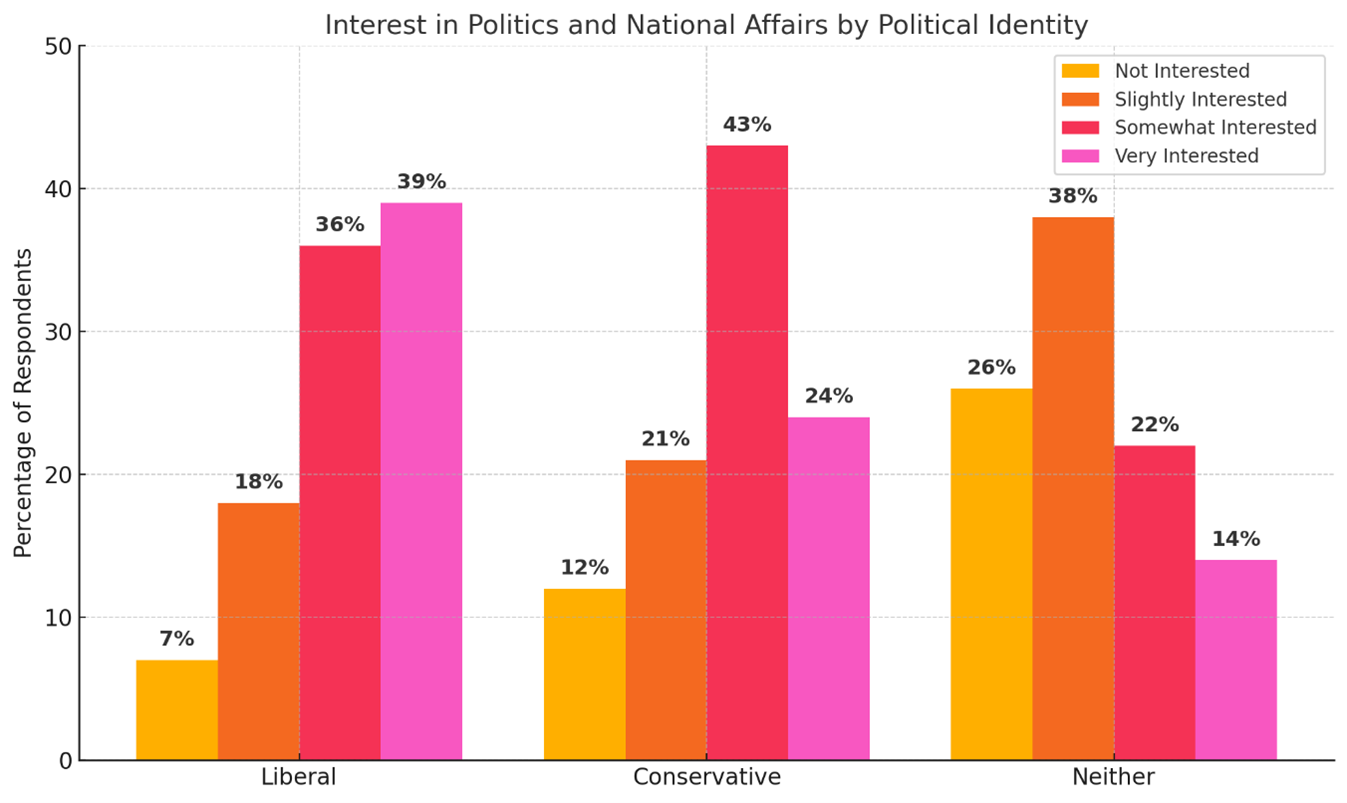

We asked students to rate their interest in politics and national affairs on a scale from “not interested” to “very interested.” The students overall were more interested than not: Only 11% reported no interest at all, while 33% chose “very interested” and another 30% chose “somewhat interested.”

There’s some evidence that liberals are generally more invested in politics — they’re more likely to donate money, volunteer, end friendships over political disagreements, and so forth. Our data are consistent with this: 39% of the liberal students reported that they were very interested, compared to 24% of the conservative students. And among liberals, those who were “very liberal” were more likely to be very interested (55%) than those who were only “liberal” (40%) or “somewhat liberal” (13%).

But the least interested in politics were actually those who identified as neither conservative nor liberal: Only 14% of them said they were very interested, and 26% of them said they were not interested at all — a number more than twice that for conservatives (12%) and over three times that of liberals (7%).1

It makes sense that people with no strong political identity also have less interest in politics — a relationship that could plausibly work in either direction. But the finding should caution us against viewing the very-conservative-to-very-liberal scale as a simple ordinal variable measuring the degree of liberalism or conservatism. The neithers might be qualitatively distinct. For instance, in our sample, students who weren’t US citizens were far more likely (30% versus 8%) to be in the neither category — probably reflecting the basic lack of involvement or interest in US politics and US political categories. The Asian kid who just wants to study uninterrupted isn’t a trivial part of the grad student population.

Loud Liberals

“Interest” can be abstract. How much do grad students actually talk about politics? We asked our respondents to rate how often they talked about politics with fellow grad students, with faculty in their programs, and with undergrads in their program.

By these measure the apolitical minority is somewhat larger: 30% of the sample reported that they never discuss politics with fellow graduate students, 44% reported never doing so with faculty, and 66% said they never did so with undergraduates. It thus appears relatively rare to talk politics upwardly or downwardly, and even among peers, a sizable number prefer to leave politics out of professional life altogether.

As you might expect, there’s variation across disciplines: Political talk of all kinds was most frequent in psychology, and least frequent in the hard sciences of physics and chemistry. For instance, 24% of chemistry students said they never talked politics with peers, versus only 8% of psychology students.

Across all fields there is a highly political minority: 9% report discussing politics with their peers daily and an additional 24% do so weekly; 1% discuss politics with their faculty daily and an additional 7% do so weekly, and 3% report weekly or daily discussion of politics with undergraduates.

The upshot of this is that even if many grad students don’t discuss politics, there’s a lot of political discussion going on. Any guesses as to how this highly talkative minority skews politically?

Yes: Regarding graduate colleagues, 40% of liberals reported discussing politics weekly or daily, versus 10% of conservatives and 12% of those who identified as neither. Contrariwise, non-liberals were three times as likely to report never discussing political matters with colleagues.

Only 35% of liberals never discussed politics with faculty, versus 67% of conservatives and 66% of those who are neither.2 And though all political identities were unlikely to discuss politics with undergraduates, the pattern of relative frequency is the same: 61% of liberals never discussed politics with undergraduates, versus 81% of conservatives and 80% of those who identified with neither side. Contrariwise, 4% of liberals discussed politics with undergraduates weekly or daily, compared to none of the other political groups.

If you look within liberals, you see the same pattern we saw with political interest: “Very liberals” talk politics more than “liberals” and “somewhat liberals”. For instance, for discussion with peers, 23% of very liberals do so daily, versus 6% of liberals and 5% of somewhat liberals.

To sum up so far: Liberals are a supermajority in all four fields. They are more interested and politics and talk more about politics in all their professional relationships. And the more liberal they are, the more this is so. Liberals quite likely initiate and dominate most of the political discussion that does take place, producing an influence even greater than their superior numbers would suggest.

Closet Conservatives

One might expect the conservative minority to experience discomfort with this state of affairs, and we have evidence that this is so.

When asked how often they were “treated with less respect” due to their “political, ideological, or social views,” 40% of conservatives reported that this happened at least a few times a year, compared to only 12% of liberals. Vice versa, 75% of liberals reported that this never happened, compared to 45% of conservatives.3

Such perception can shape one’s sense of belonging in the discipline. Compared to liberals (5%), conservatives (21%) were more likely to strongly disagree that “I have a strong sense of belonging in this academic discipline’s community.”4

It can also lead to fear of negative professional consequences. Conservatives were much more likely to agree with the statement “expressing my political, ideological, or social views could result in professional setbacks.” 50% of conservatives “strongly agreed” with this, compared to just 12% of liberals. and 14% of those who identified as neither.5

The conservative adaptation to this situation is self-censorship. Compared to liberals, conservatives were far more likely to agree with the statement “I avoid expressing my political, ideological, or social views around fellow graduate students.” 65% of conservatives strongly agreed, compared to only 10% of liberals. Conversely, 21% of liberals strongly disagreed with the statement, compared to only 3% of conservatives. Similarly, 73% of conservative students strongly agreed that they avoided expressing their views to faculty, versus only 22% of liberals.6

There was a strong correlation between conservatism and self-censorship. But note that even those who identified as neither conservative nor liberal were more likely than liberals to self-censor: 33% of them strongly agreed that they avoided expressing their beliefs around peers, and only 4% strongly disagreed. Likewise, 51% of them strongly agreed that they avoided expressing their beliefs around faculty. Even that apolitical minority is a little worried.

Topic tags: Academia; Politics

n=327; chi-square=33.09; df=6, p=0.000.

n=325; chi-square=31.56; df=10; p=0.000. Note the n varies a little from question to question due to item nonresponse.

n=317; chi-square=31.96; df=10; p=0.000.

n=327; chi-square=21.51; df=8; p=0.006.

n=317; chi-square=48.44; df=8; p=0.000.

n=317; chi-square=92.23; df=8; p=0.000.