Wherever you’re reading this, I appreciate your interest! This post is just a bit of spitballing in between the regular series.

Elites are people at or near the top of a status distribution. They wind up there in part because they are more apt to climb the social ladder. This can be due to stronger motivation or greater talent or some combination of the two. Either way, elites tend to be status maximizers.

But there are multiple dimensions of social status. People have different classifications, but for present purposes we’ll go with three: Wealth (material goods and the money to exchange for them), power (ability to get things done, including having people take your orders), and prestige (having a praiseworthy reputation, whether as saintly or badass or cool).

While elites are generally status maximizers, they vary in which dimension they prioritize most. Sure, none would turn down either more money or more prestige or more power (at least if power is described by its positive names, like “making a difference” or “changing the world”). And true each type of status makes it easier to get others — for example, one can buy power or parlay wealth into prestige.

It’s a bit like the verbal/math tilt in intelligence testing: Yeah, they’re both correlated enough that it makes sense to say that Person A is generally brighter than Person B, but it’s not a perfect correlation. Some people are better at math than you’d expect from their ability to digest or write a paragraph, and some are better at writing than you’d expect from their ability to do math. Likewise, dimensions of status are highly correlated, but not perfectly so.

Some people will naturally have a greater talent for winning praise than making money or making money than gaining power. And if forced to prioritize and make trade-offs, some will put greater value on prestige, others on wealth, and still others on power.

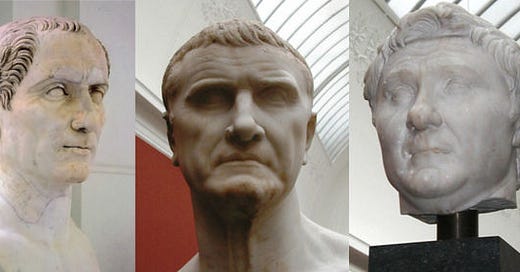

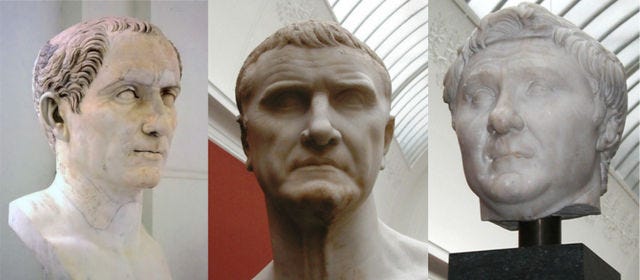

Consider the First Triumvirate, the trio of men who joined forces to control Roman politics during the late Republic. Crassus was the richest man in Rome, a wealth maximizer. Pompey was the glory hound – Dan Carlin called him a rock star. Caesar was drawn primarily to power and would eventually get it.

Crassus hungered for Pompey’s prestige but was more successful in maximizing wealth. Pompey basked in multiple triumphs, but was bamboozled by his inability to get the Senate to do what he wanted. Caesar leveraged money and prestige, but always toward the end of gaining control. When he was put to the test of choosing either to have a triumph or to stand election for consul, he chose being consul.

In modern America, wealth maximizers gravitate toward Red Tribe. Its rank and file include more people in less prestigious but economically rewarding occupations – skilled blue collar, small business. Its big leaders are more likely to come from big business. Red Tribe also has a bigger problem with its elite being full of blatant grifters.

Prestige maximizers gravitate toward Blue Tribe. The lower earning but more prestigious fields of academia and media lean heavily in this direction. Blue Tribe elite are more oriented toward public virtue and the latest moral and intellectual fashions. They’re also more into credentialism and more vulnerable to purity spirals.

Whither the power maximizers? Consider the arguments that Blue Tribe tends to care more about politics, while Red Tribe tends to “just want to grill.” Or that Blue Tribe is heir to a stronger tradition of organizing and activism.

It seems like the side with higher numbers of power maximizers would do better at getting its policies enacted. I wonder if the degree to which the winning coalition has relatively more prestige maximizers or wealth maximizers varies over time.

I would guess, based on Joseph Henrich’s work on the importance of prestige status for social influence, that power can, if push comes to shove, do without wealth more easily than without prestige.

Sufficient power can generate its own prestige, but initial victories against an already prestigious opponent only make one a notorious enemy among the opposing coalition. Thus the path to power against an already prestigious opponent might involve a kind of fitness trough that is difficult to plow through.

Frankly I don’t know how to squeeze any testable hypotheses out of this, but if you know more about the macrosociology, stratification, or politics maybe you can give it a go.

A subscription too much committment? Then leave a tip in the Tip Jar.

I really appreciated this one.