Links for April, 2025

New Book, China Rising, Gods, Cults, Identity Politics, Trauma

Welcome! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, you can leave a tip at this Stripe link (change the amount to whatever price you like). Or become a subscriber with the button below.

Now on to the monthly roundup of interesting items, starting with some big news:

Working on the Water

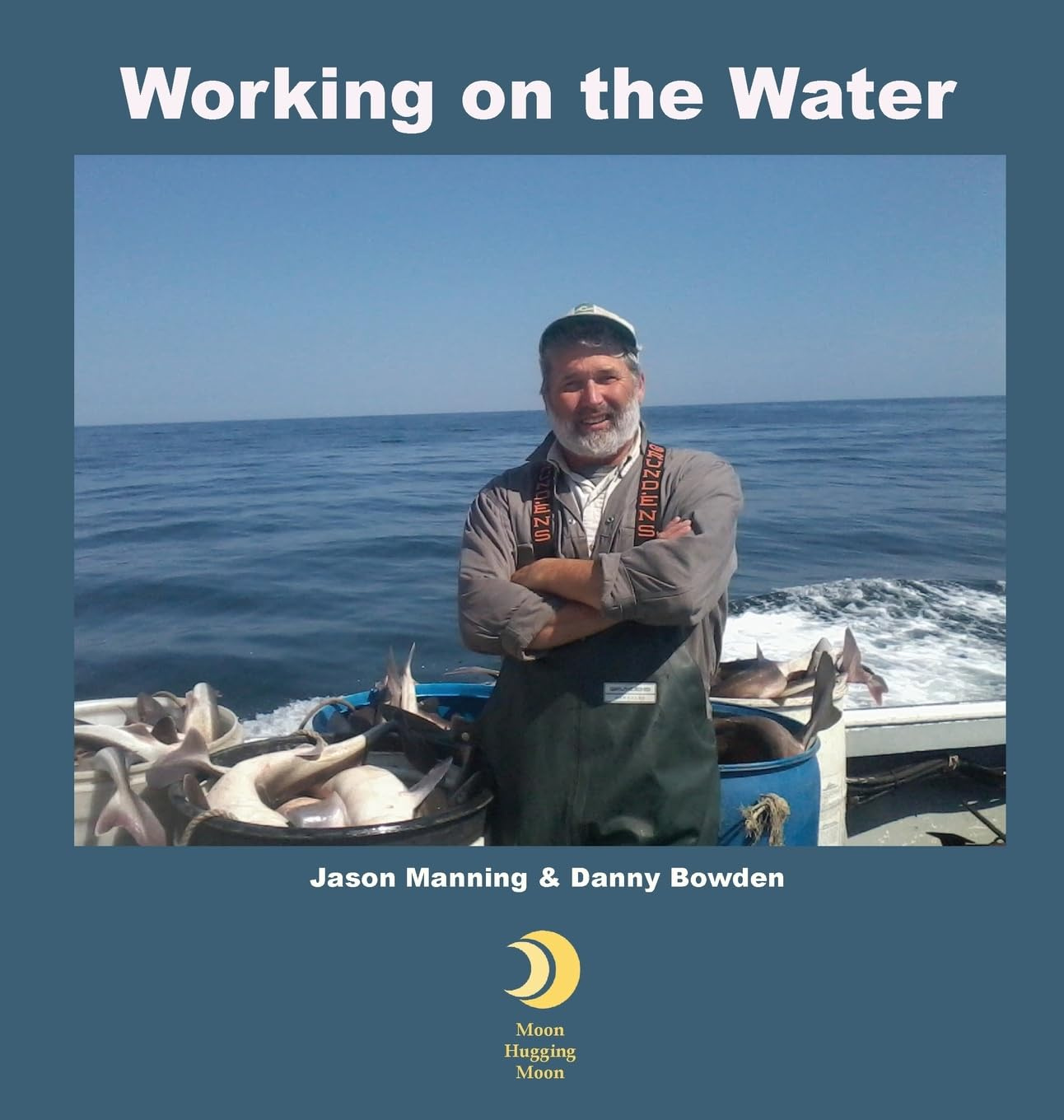

I grew up on Chincoteague Island, on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. A lot of my ancestors made a living in the seafood business (“working on the water”) and my Uncle Danny still works as an independent commercial fisherman — a waterman.

I wanted my kids to have some reading material about their heritage. But I couldn’t find any good children’s books about commercial fishing in general, let alone the specifics of how it’s done around the Eastern Shore and Chesapeake Bay. So with help from Uncle Danny, I made my own:

Working on the Water is aimed at kids, but is interesting and educational for adults as well. Using lots of photos, it covers things like the types of boats watermen use, how they set their nets, what species of fish they catch, and how they collect clams, crabs, and oysters.

The hardcover version, of which I’m most proud, is published via the print-on-demand service Ingramspark. You can use this link to order it for lower than the list price.

The softcover version is published by Amazon KDP and you can buy it at this link. It’s the cheaper option, especially if you have Prime shipping.

If you’re in the neighborhood, The Museum of Chincoteague Island will be carrying copies this summer. If you too run a shop and would like to carry it, contact me about wholesale pricing.

Buy a copy now to learn about a tradition before it disappears!

Dragon and Eagle

Last month I linked Stephen Hsu’s podcast on “China Today: Myths and Realities.” Hsu, an American physicist whose parents came from China, often talks about China’s rapid advances in science and technology. Here’s his latest podcast, including discussion of the current trade war. An economist posted a lengthy comment on the video, explaining the losses from trade war and positing US disadvantage. Excerpt:

The reason that some people in the US are not panicked as they should be and might even think they have the upper hand is that they have some combination of unrealistic assumptions in the form of 1) US resources allocated to distributing Chinese imports can be redeployed quickly to next best economic uses without much loss of economic value. 2) Chinese imports can be easily substituted with imports from somewhere else and even if there are cost increases those costs increases are not high. 3) Chinese resources allocated to producing exports can not be redeployed at all and have no alternative economic uses.

Now all of these assumptions if you just follow some basic common sense and business knowledge are completely wrong.

At Unherd, Wessie du Toit writes “Why China Will Beat the West: A New Supercycle Has Begun.”

“Supercycle” refers to “an extended period of high prices for raw materials. Since the Industrial Revolution, the world has seen five supercycles, coinciding with major bursts of economic development or war.” The last supercycle was the result of Chinese development:

Iron ore was the signal substance of Chinese growth — by 2024, its price was almost 1,000% higher than in 1995 — but all kinds of resources were sucked into the whirlwind: oil and coal, nickel and copper, soybeans and rubber and wool. In recent months, though, analysts have been announcing the end of the two-decade China supercycle.

People talk about Western manufacturing “moving” to China. Here’s a quite literal example:

1,000 Chinese workers arrived in Dortmund, a city in Germany’s Ruhr region. They had come to dismantle a large steelworks. Steel had been produced at the site since 1843, employing 10,000 workers at its peak. Now ThyssenKrupp, a German conglomerate, had agreed to sell the plant to the Chinese firm Shagang.

The enormous industrial edifice, complete with a seven-storey blast furnace, would be packed into crates and shipped 9,000 miles to Handan, a city on the Yangtze River north of Shanghai.

du Toit says a next supercycle, just getting started, “will be driven by the minerals used in renewable technologies and advanced computing.”

He thinks this will involve a scramble for rare earth elements, and that China has a head start.

Also on China strategy, Tanner Greer writes on the strategic ambiguity of the Trump Administration: “Obscurity by Design.” The ambiguity is less a matter of playing cards close to the chest than there being a diversity of views within the administration, all of them jockeying for the attention of a noncommittal executive. Greer’s essay classifies and discusses these views. Notably, the factions differ as much or more in their understanding of America as in their understanding of China. And whether the friction between them will produce any coherent action is an open question.

Related to questions of trade and deindustrialization: At Unfolding the World, a guest post by strategist Martin Skold on “A Dilemma about a Dilemma: The Paradox of Trying to Reindustrialize While Preserving Dollar Dominance.” Excerpt:

The basic problem with dollar dominance is that reserve currency status effectively starts a clock, via something known as the Triffin Dilemma.

The basic idea is that the thing you own ends up owning you. Reserve currency status subsidizes your own challengers and eats away at your industrial (and therefore military) power.

Later:

It’s argued, anyhow, that the Trump tariffs themselves, if actually carried through, amount to strategic dollar devaluation. But however you choose to do the accounting, it should come out about the same: The petrodollar system and the dollar’s reserve status have to be up for discussion because the system that sustains them is about to go critical.

Here’s an odder one that came across the transom: From 2013, we have “The Strategic Consequences of Chinese Racism.” Short version: Han supremacy provides asabiyyah, but a competitor could use to drive a wedge between China and allies. As far as I can tell the author was this guy. 5/1: Whoops, basic reading fail: It was submitted to that guy. Author was Bradley Thayer. Thanks to Whyvert for pointing out the error.

Tangential: Empire of Dust is a pretty good documentary on Chinese workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2011, and you can watch it for free here.

I AM and Aesir

University of Georgia Bible scholar Richard Elliot Friedman shares his entire course on the Hebrew Bible on Youtube. The course focuses on the Torah and the historical books, following the narrative from creation up to the return from the Babylonian exile.

Friedman frequently emphasizes the importance of this linear reading, noting that the continuity — cause and effect, setup and payoff, developing themes — is usually lost on those of us who grow up learning individual Bible stories.

One theme he emphasizes is the withdrawal of God. You start out in Genesis and Exodus with lots of direct interaction with God and large-scale public miracles. But the last big public miracle happens in first Kings, and by the time you get into the later historical books it’s mostly the near-eastern game of thrones. The book of Esther doesn’t even directly mention God. Sociologist Max Weber spoke of the disenchantment of the modern world — perhaps we’re seeing here the disenchantment of the ancient one.

After spending most of the course addressing the narrative as such, Friedman turns to historical questions about how and why it came to be written that way and what it could tell us about things like the role of the Levites the process by which Israel and Judah developed true monotheism.

It was a bit jarring to go from Friedman’s lectures to the book I’m currently reading, Neil Price’s Children of Ash and Elm: A History of the Vikings. For it begins with the traditional Norse worldview: The complex cosmology involving nine realms (ours made from parts of a giant’s corpse) somehow all connected to an enormous world-tree (perhaps inspired by the Milky Way), the four-fold conception of the human soul (with some parts semi-autonomous), and the various gods with their distinct personalities and attributes and tangled family tree (even Odin’s six-legged horse was birthed by a shape-shifted Loki).

What’s striking in comparison is just how little cosmology the Bible has. The Creation and the Fall go by pretty quickly and we’re on to pastoralists tending flocks and drawing water. There are a few lines suggesting the ancient Israelites conceived of earth as a dry bubble between waters above and below, but otherwise not a lot about the structure of the world or the universe, where God dwells, or any of that. Even from a Christian perspective, it’s odd that the Old Testament doesn’t say much at all about the soul or the afterlife. Israelite religion was very focused on the here-and-now.

There’s not even much about God Himself! The Hebrews had to be content with “I am what I am.” (God’s name, Yahweh, is usually translated as “I Am,” though Friedman suggests the Hebrew verb form is closer to “I Cause.”) Friedman has a couple of quips about how Jews don’t do theology — God is, He told you what to do, what else do you need? He attributes the more complex theology of Christianity to cross-pollination with Greek philosophy.

Cargo and Cult

For another contrast, consider that one of the gods of the people of Madang, New Guinea, was Russian anthropologist Baron Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay.

He gave the New Guineans gifts of metal tools, mirrors, cloth, beads, paint, and the seeds of unfamiliar plants, so naturally they decided he was a new god who had invented a new type of material culture and was now coming to give it to them.

When subsequent visitors weren’t so friendly, the locals concluded that while Maclay had been one of their own gods, these new visitors were hostile foreign gods. But eventually they realized that these strangers were mortal men after all. So they switched to asking why the foreigner’s God gave so much stuff, while their own gods only repaid their rituals with yams. Thus began the evolution of the cargo cult.

All this is from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, which gives a lengthy review of Peter Lawrence’s Road Belong Cargo, an account of a Melanesian cargo cult. If you’re not familiar:

“Cargo” is the catchall word for Western material culture in Pidgin English, the lingua franca of New Guinea’s many language isolates, and New Guineans were understandably obsessed: before European contact, they were living in the literal Stone Age.

….So of course as soon as they encountered cargo — especially steel tools, tinned meat and dried rice, and cotton cloth — they wanted it desperately. And they almost universally believed they could get it by ritual activity.

New Guineans first sought these rituals in Christianity, since that was what the colonists practiced. Thus the first cargo cults were a Christian heresy, though language barriers kept the missionaries from noticing what was going on: “relations between natives and missionaries, although on the whole extremely amicable, were nevertheless based on complete mutual misunderstanding.”

When the hymns and prayers didn’t result in cargo, the natives added epicycles to their theory, resulting in resentment of the bad people intercepting those cargo shipments God was now sending them. Then came the messiah: Yali, who is indeed the same Yali mentioned at the outset of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel. He didn’t set out to become a messianic figure, but one thing led to another….

I don’t want to regurgitate the entire post, so I’ll just say the whole thing is worth a read.

Identity and Victimhood

Brian Martin gives an overview of various attempts to characterize and explain the cultural shifts of the past decade or so — whether as political correctness (Jeff Sparrow), elite capture of non-elite movements (Olúfémi O. Táíwò), woke capture of the left (Susan Neiman), the identity trap (Yascha Mounk), the rise of symbolic capitalists (Musa al-Gharbi), or the rise of victimhood culture (Bradley Campbell and myself).

He characterizes us all as “sympathetic critics” who “differ in their prescriptions for change. The question is how to pursue social justice. One theme is support for universal values, values that apply to all humans, without distinction.”

Recall that Campbell and I said victimhood culture wouldn’t stay contained to the progressive left. Along those lines, consider this article on victimhood rhetoric deployed by white nationalists.

See also “Virtuous Victimhood as a Dark Triad Resource Transfer Strategy” in the journal Personality and Individual Differences.

Miscellaneous

A 2007 report on the UK jury system claims (with some qualifications) that in simulated juries, the jurors are more lenient on same-race defendants. The basic effect is explicable with Donald Black’s theory of partisanship. In this interview, Black discusses race and partisanship among jurors and the public during the murder trial of O.J. Simpson.

A study of Norwegian troops claims that killing in combat predicts trauma among those on peacekeeping missions, but not those on combat missions. The authors connect it to moral injury, though my first worry is selection effects. Also on trauma among veterans, see Justin Snyder’s “Blood, Guts, and Gore Galore: Bodies, Moral Pollution, and Combat Trauma.”

Amos Wollen presents “And Then There Were None,” starring all the big bloggers dying in amusingly appropriate ways. Hanania is a vampire.

At the Institute for Family Studies, Nadya Williams discusses “The Joy of Inefficiency: Teaching My Kids How to Read.” I don’t exactly regret efficiently teaching my son to read, but do miss how often he used to ask me to read to him. Won’t be the last phase of his childhood I miss — the time goes fast.

Speaking of kids: Did you already forget I have a new children’s book for sale? Go ahead and buy a copy! (Hardcover here; softcover here.)

Thanks for reading! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, please leave a tip at this Stripe link or become a subscriber with the button below.

Substackers cited above:

; ;