Thanks for checking in! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, you can leave a tip at this Stripe link. Or become a subscriber with the button below.

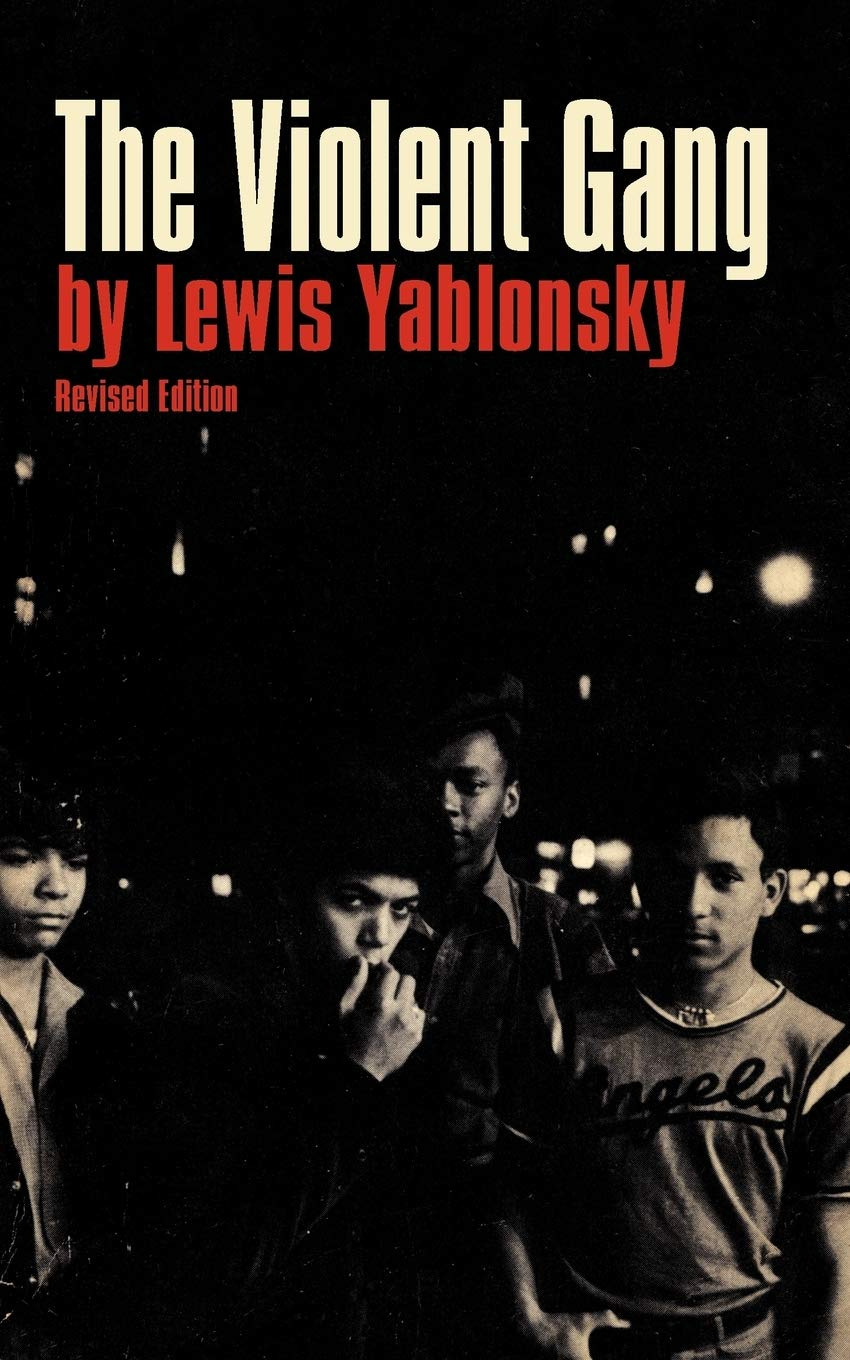

During the 1950s, criminologist Lewis Yablonsky was crime prevention director of Morningside Heights, a neighborhood on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, near Columbia University. It was a job that brought him into close contact with the area’s violent youth gangs.

He first heard of a local gang called The Balkans through the newspaper. The report described how police broke up a large mass of youth assembling for a rumble — a big gang battle — at Grant’s Tomb. The rumble pitted the Balkans, backed by allies from Harlem, against an alliance of the Villains and the Scorpions from Riverside Park. Thanks to the police, the fight was over before it started. Cops managed to arrest 38 youths while the rest scattered.

Curious about this new gang in his own backyard, Yablonsky cold-approached a neighborhood street tough and asked him about it. Once satisfied that Yablonsky wasn’t a cop, the kid said: “It’s too late to help us; we’re all messed up. Some of our guys are locked up and we’re going to get the bastards who did it.”

After further conversation, Yablonsky obtained an introduction to the Balkan’s leader, Duke. Yablonsky established rapport with Duke, and with that came a close relationship with the gang. Through his efforts to curtail their violent activities he was able to learn something about the gang’s history, structure, and members.

The Birth of a Gang

In The Rise of Victimhood Culture, Bradley Campbell and I wrote:

The dynamics of conflict can lead adversaries to become more similar to one another over time as they competitively adopt one another’s tactics, strategies, and forms of social organization. For example, violence often begets violence, and organization on one side often begets organization on the other. According to criminologist William B. Sanders, this dynamic can cause the formation of new street gangs. For example, the original members of San Diego’s Del Sol gang were a group of teenage boys from a new housing subdivision, Del Sol, which had been built in between two communities with established gangs. The Del Sol boys often faced challenges and attacks from members of these gangs . . . Tiring of this harassment, several Del Sol boys decided to . . . respond aggressively to verbal challenges by claiming membership in a Del Sol gang, and retaliate if attacked. They soon became a recognized part of the gang landscape, engaging in violent conflict with rival gangs.

Yablonsky reports a similar pattern in 1950s Morningside Heights. According to Duke, the Balkans began when boys from the Scorpions and the Villains began coming into Morningside Heights to rob local boys of their money, watches, and rings.

The first act of collective retaliation came after some Villains, led by a boy named Blackie, beat up Mike, “the most popular guy on the block.” Three of Mike’s friends decided to travel into Villain territory to “beat the hell out of this guy Blackie for what he had done to this friend of ours to teach him a lesson.”

Though they didn’t find any targets that night, the idea of collective retaliation stuck. Duke decided that the best solution was a big fight to “teach everyone a lesson once and for all.” Through some unspecified channels he communicated with Blackie, who confirmed that a big fight at Grant’s Tomb was “on.”

Duke’s circle of neighborhood boys didn’t even have a gang name yet. All the same, he started sounding out “brother gangs” to be his allies in the upcoming rumble. One of his friends had a cousin in Harlem, and through this connection he was able to gather “all of the Presidents” of the Harlem Syndicate at a meeting in his basement. Through them, word went out to gangs in the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. Duke could name a dozen or so, including the Diablos, the Young Lads, and the Fordham Eagles, all drawn into this chain of partisanship.

As forces began to gather at Grant’s Tomb, the police arrived. Duke and his friends were the bulk of those arrested.

While the arrest stopped the fight, it also helped solidify the gang and its identity. The boys didn’t have a gang name until a cop asked them about it and one boy, Jay, blurted out “‘Call us Balkans, call us Balkans.” Jay had recently learned the term in school and thought it sounded cool.

The news coverage cemented their name and reputation, gaining them recognition in the streets as a “bopping gang” with a specific territory, known enemies, and a proven willingness to fight. The boys took pride in this notoriety.

If it was another street gang that catalyzed the Balkans, it was the law and media that crystalized them.

I think we see something similar in history whenever states interact with tribal people. Temporary tribal coalitions, incipient confederations, mixed groups of refugees — the state, seeing like a state, prefers neat categories and simple labels for the basis of its trade and diplomacy. Its subsequent dealings with these categories can then transform them from administrative fiction into sociological reality.

Keep this lesson in mind.

Patterns of Gang Violence

Attention from the police and Yablonsky’s crime-prevention agency deterred the boys from planning another “all-out rumble.” But there were still skirmishes and confrontations.

Most such violence, like gang violence in general, took a form that goes back to the Stone Age and beyond: The hit-and-run raid. A small band of aggressors from one group sneak into the territory of the other in search of a vulnerable target. The violence is situationally unilateral, a lone individual or pair of the enemy ambushed by superior numbers with little opportunity to resist. But each attack is part of a reciprocal pattern, the two groups trading raids back and forth over time.

Among the youth gangs of 1950s New York, these sneak attacks were called “Japs,” after the Japanese forces in World War II.

In tribal warfare and classic blood feuds, raids and ambushes are lethal. But among these 1950s youth gangs, the attacks usually stopped well short of homicide. Though Yablonsky does describe one brutal murder arising from such an ambush, the common pattern was a quick beatdown followed by flight. The relatively low lethality is notable, especially in comparison to the drive-by shootings of a later generation of gangbangers.

Yablonsky notes a rarer pattern of violence that sounds like something out of The Iliad: When two opposing groups of roughly equal size run into one another, they sometime agree to combat of champions. Says one Balkan:

We went up to Grant’s Tomb and nobody was there. As we started to leave we ran into about 20 or 30 Villains and Scorpions. It was decided that I and two boys would fight against Chino, Animal, and this boy Lefty. The others would be peaceful.

Given the steady trickle of attacks and clashes, Yablonsky feared that the conflict between the Balkans and the Villains-Scorpions would build into something bigger. He tried a few different strategies to preserve the peace.

The Baseball Intervention

One was a classic diversion strategy, based on the idea that the gang boys would fight less if they were given more wholesome pastimes. Yablonsky arranged for the Balkan boys to have access to the baseball field at Columbia University, and so they started having regular ballgames there.

The baseball intervention had two main results.

The first result was it altered the gang hierarchy. Some formerly nondescript members turned out to be good at the game. Their elevated status on the field gave them greater overall status in the gang, and some moved into leadership positions. Vice versa, some existing leaders turned out to be bad at baseball, and their stature declined.

This happened to Duke and his second-in-command, Pedro. They reacted to this decline with increased violence against the other members — as Donald Black proposes, violence is a direct function of vertical mobility. After beating up several fellow Balkans to assert his authority, Duke developed a suspiciously convenient shoulder injury that allowed him a face-saving exit from playing ball and stabilized his position as gang leader.

The second result of the baseball intervention was that it raised the stature of the Balkans as a whole and attracted new members to the group. The Balkans now had access to a prestigious resource — Columbia Field — and neighborhood boys who wanted to play there were attracted to the Balkans. In this, Yablonsky’s strategy backfired.

Making Peace

There was still rumbling about a brewing gang war. So Yablonsky switched from a strategy of diversion to a strategy of settlement: He set out to directly mediate the gang conflict.

Thus, after much back-and-forth, he managed to arrange a summit between the two sides, with the leaders of both factions meeting in his office to work out a peace treaty.

The meeting of June 25, 1954, was extremely tense, with both sides griping that the other was untrustworthy and just needed to have their skulls cracked. But in the end, both agreed to sign a document guaranteeing nonaggression and limited rights of free passage through one another’s territories.

The “Japs” didn’t completely cease. As one Balkan member put it, “You gotta keep moving. If you slug a guy every so often, they know who’s boss and you get the first shot in. That’s better than getting hit first, ain’t it?”

But overall, the treaty did produce a decline in gang violence. You might say the peacemaking intervention was successful.

Yablonsky himself had doubts. Remember that lesson I told you to remember?

The Dragon Invasion

Like tribal confederations around the fringes of some ancient civilization, gangs frequently merge to form new gangs. When they first tangled with the Balkans, the Villains and Scorpions were in the process of consolidating into a unified gang called the West Side Dragons. They adopted this name to demonstrate a connection to the increasingly prominent East Side Dragons.

The East Side Dragons, under the leadership of an unhinged twenty-something named Frankie Loco, were an expansionist power. Dragons would arrive in new neighborhoods and forcefully draft local boys into their gang. Or they would, as with the Villains-Scorpions, bring entire gangs under their banner.

The newspapers carried reports of this growing gang empire. One 1955 item reported that the Dragons — “the toughest and oldest” of Manhattan’s gangs — “has already absorbed 400 to 600 youngsters” from various other gangs, including the Villains and Scorpions.”

The Balkans and their allies in Harlem increasingly spoke of the threat from the Dragons, and made plans to deal with it.

Duke appointed a new gang president, Jerry, referring to him as “supreme commander” in the looming conflict with the Dragons. Jerry, a 24-year-old Puerto Rican, would make passionate speeches about “his people” and go on monologues about the number of fighters in the Balkan divisions and their allied gangs.

Jerry began telling Yablonsky that the real leader of the Dragons was an inmate in Sing Sing Prison named Cherokee, who was organizing a city-wide syndicate from behind bars. Yablonsky suspected this was bull, but in the interest of getting more information he took Jerry to see the local police captain. There Jerry requested that the Yablonsky and the captain arrange a formal visit between himself and Cherokee. When they responded only that they would think about it, Jerry offered to call all of the important gang leaders in New York for a meeting at Grant’s Tomb, where the police could arrest them — “and we will have peace.” They again told him they’d consider it.

Two days later, reportedly in fear of the Dragons, Jerry left for California and was never seen again.

During this period, Duke kept a journal. He later shared it with Yablonsky, who observed that it “read something like Hitler’s Mein Kampf.” It detailed Duke’s grand plans for an expanding city-wide gang alliance, as well his paranoia over the strength of his enemies. During the height of the Dragon invasion, pages of the journal were dedicated to enumerating the number of fighters Duke could muster. For instance:

“The 5th division is to be held in reserve unless we need them in extreme need and then they are to be given 2 weeks’ notice. They are 70 strong. The Saints and Anzacs will combine to protect La Salle St. and 122nd St. from attack — combined, they are 61 strong . . . If we called in brother clubs we could have:

Red Wings—300 strong, plus 400 Balkans, plus 20 ROD Knights

Tiny Tims—300 strong, plus 21 Anzacs, plus 30 Seahawks

Politicians—500 strong, plus 40 Saints, plus 100 Dwarfs.

There were pages and pages of that sort of thing.

With the loss of Jerry, Duke was more worried than ever. He had many nominal alliances with brother gangs, but little confidence in their commitment. He wrote in his journal that “things do not look good for us.”

In a sense, he was right to suspect the alliances wouldn’t amount to much. But that’s only because all of this was make-believe.

Debunked to Extinction

By this time Yablonsky had gotten fairly close to the Balkans, who had also introduced him to the leaders of the Harlem Syndicate: “Most of them were Puerto Rican or Negro youths in their late teens or early twenties. Each was introduced with a title: ‘president,’ ‘war lord,’ or ‘war counselor.’”

From these meetings Yablonsky concluded that Duke was indeed accepted as a gang leader among other gang leaders. He also concluded that the gang leaders

all seemed to support one another’s stories on what seemed to be fantastic descriptions of gang size and alliances. Some would work themselves up to a fever pitch, while others would cooly discuss their empires, mingling plans with threats of violence to invaders.

The talk of multiple divisions and hundreds of fighters seemed increasingly crazy to Yablonsky. In his months hanging around the Balkans, he’d only ever laid eyes on 25 of them.

And as far as he could learn by conferring with other agencies, the East Side Dragons also had only 20 to 30 core members. “Drafting” new boys into the gang seemed to consist entirely of Frankie Loco and a few friends roughing up a lone stranger, telling him he was now in their gang, and then disappearing with no further contact. It was just a psycho and his buddies throwing their weight around.

As for entire gangs coming under the Dragon banner, it was a self-reinforcing cycle of rumor and newspapers playing up the Dragon threat, thus encouraging unrelated gangs to adopt the prestigious and intimidating name.

By this point Yablonsky had had second thoughts about brokering the peace treaty. He worried that, much like the recognition of the Balkans by the police and newspapers, his intervention had helped formalize something that would otherwise be loosely structured and undeveloped: “The meeting had confirmed the fact that there was trouble brewing between rival groups. Now two ‘gangs’ had a war truce.”

He was wary of making the same mistake with this Dragon threat, and when he saw an opportunity to take the opposite approach, he seized it.

He'd been allowing the Balkans to meet in his office to discuss their problems. During these meetings, Duke produced a detailed, multistage plan for counterattack that involved mobilizing the Balkan’s various divisions and allies to take and hold territory in strategic order. But as the meetings recurred, more and more of those present began to express skepticism of his plans, and especially at his estimates of the Balkan’s numbers:

At one meeting when several ‘core’ members became carried away with enumerating the many Balkan divisions and thousands of members, Andy, a more marginal Balkan, seemed to reflect many of the boys’ feelings: “I think all you guys are full of shit. I ain’t seen no one but the guys here.”

Yablonsky decided to start gently siding with the skeptics and deflating the core member’s fantastical claims. As a result, “some of the boys began to view Duke and Pedro as ‘psychos,’ and the Dragon threat as a wild rumor.”

Duke made increasingly desperate attempts to convince Yablonsky himself of the size and danger of the Dragon empire, but Yablonsky wouldn’t humor him. More marginal gang members in the community also started routinely debunking gang rumors, and the gang’s “clowns” made these and other claims of their leaders an object for mockery.

With this, the stature of the core members fell. The gang shrank as marginal members drifted away. Violent conflicts with other gangs declined. Soon the Balkans went extinct.

The Youth Gang Phenomenon

That a gang can be debunked out of existence says quite a bit about its nature, especially in comparison to other sorts of violent group. One wonders if his strategy would have worked with the 19th century gangs of New York’s Five Points, or with the gangbangers of 1990s Los Angeles.

While Yablonsky was writing too early to compare to latter, he did compare his gangs to those from earlier times. He thinks the most distinctive feature of the 1950s youth gangs is the youth part — the degree to which the gangs of his period are segregated from the adult social world.

Gangs of 19th century New York, like the Dead Rabbits and Bowery Boys, were more integrated into the fabric of their respective communities. Their membership included older men with families and jobs. The Dead Rabbits worked for the political machine at Tammany Hall. And gang leader Bill “the Butcher” Poole was a businessman and politician.

Even in the early 20th century, when gang membership was more limited to boys yet to take on adult social roles, gangs were still closely tied to adult institutions. The Chicago gangs of that period were likewise part of the city’s political landscape. The Ragen Colts, an Irish gang that took a leading role in the 1919 race riot, were named for the county commissioner who funded them. And Chicago mayor Richard Daly was a gang member during his youth, showing that being in a fighting gang wasn’t just for dead-enders.

The violent street gangs of the 1950s look more firmly and fully like a youth-bound oppositional culture. Even at the local level, in the poor neighborhoods and ethnic enclaves most conducive to them, they enjoyed little open support from the adult populace.

Yablonsky’s gangs didn’t even have ties to the “adult” institutions of the criminal underworld. Prohibition era street gangs were often enforcers or even junior wings of organized crime syndicates — whose leaders, like Al Capone, were themselves street gang alumni. But in the postwar period, gang-to-gangster wasn’t much more likely than gang-to-mayor. Gangs like the Balkans were quite firmly disorganized crime.

Yablonsky also identifies three contrasting types of 1950s youth gang. The social gang is cohesive and has a collective identity, but their activity mostly revolves around respectable pastimes: They organize sporting competitions, dances, charity drives, and so forth. They resemble a youth version of adult fraternal associations, like the Elks or Masons, or non-college version of the Greek Letter fraternities. They seem to crop up in tight-knit but peaceable enclave communities, and have a group identity that survives even as their members transition into adult roles.

It seems to me that, just like the old fraternal orders, this sort of “gang” has since gone the way of the dodo. But I think one can find some faint echo of it in something I observed in college — a circle of friends coming up with a “crew name” and sometimes jointly planning parties or outings.

The second type is the delinquent gang, a group who comes together primarily for illegal profits, especially predatory crime. These tend to be small groups, a “tight clique” that is mobile enough for robbery and burglary jobs and can trust one another not to snitch. Suspicion of new guys makes it hard for outsiders to become members, and the gang generally evolves out of pre-existing strong ties.

Yablonsky characterizes the typical member as “emotionally stable” — hotheads and psychos are too unreliable for such ventures. They might be immoral, but they’re not irrational — like Mr. White and Mr. Pink, they value being a professional. Only in the 1950s context, there’s no clear-cut criminal career path to follow, no larger criminal hierarchy to climb.

The third type is his focus: The violent gang, or what kids at the time called a “bopping gang.” Their activities mostly centered around violence, usually conceived of by members as defense of their territory from outside aggression. They fight a lot, and when they’re not fighting, their conversations center around conflict. Gangs make fights, and fights make gangs.

The Social Organization of a Violent Gang

Before they disbanded, Yablonsky took advantage of his close relationship with the Balkans to conduct research on them. He recruited Duke and some other gang leaders to survey their fellow members, as well as other boys in their neighborhood and in allied gangs. Their technique for recruiting respondents wouldn’t get past a modern IRB — in at least one case, Duke told a reluctant respondent, “You fill it out cause I say so.” But the result is some rare data on 126 different gang members, 51 of them Balkans.

The Balkans were ethnically and racially mixed, with Puerto Ricans the largest group, followed by whites, then by blacks. Such mixed gangs might be far less common than 1980s Hollywood would have you believe, but they were something that happened in mid-twentieth century New York.

About a third of the boys were aged 12 to 15, just over half aged 16-19, and about 14 percent aged 20 or older.

There was an age schism in the gang, with the younger members considered a different “division” than the older members. The older division — in their late teens and early 20s — was considerably smaller but highly visible, as it was the core membership and leadership of the gang. Young members often wrongly assumed there was a larger periphery of older members outside of this core, feeding their perception of the size and strength of the gang.

The members’ estimates of gang size were as variable as they were inaccurate, ranging from 80 to 5,000. Yablonsky observes that there were about 25 regular members he consistently observed hanging out on the street or showing up to his office. They were the ones most involved in fighting, in recruiting new members, and “in selling the myth of the large size and fighting power to anyone who would listen.”

Membership in Yablonsky’s gangs was extremely fluid: Entry into the gang was as easy as hanging out with a group of members, and leaving was as easy as not showing up. There was a constant churn of marginal members who “joined” for weeks or days before moving on to something else. While undercutting the group’s solidarity, this fluidity helped bolster the leader’s fantastical beliefs about the gang’s size — they were, after all, constantly seeing new members.

There was a similar fluidity in the network of alliances between gangs. These changed with the weather, and were often no more than passing verbal agreements that were never put to the test of a real fight.

Yablonsky generalizes that the Manhattan youth gangs of his time were groups of low organization and porous boundaries — “incoherent structures, with mixed values and goals” and “limited cohesive quality.” Each had a core of committed members with some sort of leadership, and a large periphery of marginal members who phased in and out of gang activity.

The gangs as discrete identities were often short-lived, as they were constantly merging or dividing or disbanding. Core members often stayed involved in gang life throughout these transitions, moving from one gang to another. The gang members themselves recognized this. As one put it, “Man, in bopping gangs the gang names change but most of the faces stay on the scene.”

When Balkan boys were asked to identify their leaders, they almost always named Duke, Pedro, and a few other core members (but note Duke and Pedro were often the ones handing out the surveys). The leadership roles were typical of other gangs in the area. As one Egyptian King put it: “First, there’s the president. He got the whole gang; then there comes vice president, he’s the second in command; then there’s the war counselor, war lord, whatever you’re gonna call it — that’s the one that starts the fights.”

Leaders usually came to the forefront through impressive talk and aggressive action. As one of the Villains told Yablonsky: “When the average gang starts out, they have a leader based on their own characteristics. The guy who talks the most and is most impressive in his speech, the guy they can ‘respect’ or look up to.”

It also helps if the leader is older and has a “‘bad’ way of talking.” Being good with girls is a plus, and while being personally strong or skilled in fighting isn’t crucial, “the average kid looks up to conquest, whether it’s physical or anything; that is, a guy beating up another guy or a guy making out with a girl, or a guy stealing money.”

It seems like success in general breeds status and status breed leadership — hence the threat to Duke’s leadership posed by his failures on the baseball field. But status can be conjured up by selling others an exaggerated picture of the gang’s membership and network of allies.

Who Joins a Gang?

We might think that Yablonsky’s attempt to divert the boys away from gang life with baseball games was naïve. But it does seem that a great deal of the gang’s criminal activity is at least as recreational as it is predatory or moralistic. They vandalize property and attack acceptable targets just for something to do. The boys involved in the gang have little else to occupy their time, especially in the summer. They find one another “sitting on the stoop, you know, doing nothin’” and do this until one of them suggest an activity, such as a movie, stickball, or “let’s go break windows for some excitement” or “come on, man, let’s go boppin.’

The marginal members who rotate in and out of gang “membership” are probably bored kids joining up with whatever excitement is at hand.

The core members are a different story. Yablonsky talks at length about how they come from broken homes and abusive families. And they generally seem like losers in other walks of life — the gang is the only place where they might exert dominance or otherwise gain stature.

Speaking of how one Balkan boy, Nicky, was frequently abused by this father, Yablonsky observes that Nicky “'lost his fights at home but won them in the street.” And there seemed to be a correlation between how bad things were going at Nicky’s home and how many fights street fights he started.

Even gang members themselves recognized the dynamic. As one put it: “Some guys are nowhere at home and school, so they’re always trying to show what big men they are with the guys.”

Yablonsky sees gang life as most attractive to “emotionally unstable” boys. They cling to the drama as a way to deal with severe personality disorders and family problems. The stories about their own gang’s size and strength, or of the vast network of alliances with brother gangs, is a power fantasy, albeit a shared one: “Gang alliance ‘contracts’ are usually mutual distortion associations.”

Absent gang life, such boys turn to drugs and alcohol — a fate that befell some core Balkan members after Yablonsky’s debunking efforts broke up their gang.

Of course, in addition to those who seek status and meaning, there are those who just really like hurting people. Author Frank Herbert had a line about how it isn’t so much that power corrupts, it’s that power attracts the corruptible. We might take a similar view of gang life: It attracts those inclined to violence.

The Dragon’s leader, Frankie Loco, got his nickname in part from a stint in the Bellevue mental hospital. He had a job cleaning up blood in an operating room and seemed fascinated by the substance itself, mentioning it constantly in conversations. Gang members considered him genuinely crazy, though his reflexive violence made him feared.

José, a Puerto Rican immigrant who joined the Dragons before moving on to the Egyptian Kings, appears to be a psychopath. Even before joining the Dragons, he had a tendency to lash out against unsuspecting and innocent targets. Another street gang actually refused to admit him because he was too wild and crazy for their tastes. But Frankie Loco welcomed him, and after witnessing him stab a boy on a dare, promoted him to war counselor.

The promotion was great for José — not just because it gave him a little more stature in the gang, but because he “could legitimately go on a Jap almost every night.”

Later, while on a raid with the Egyptian Kings, José stabbed a boy to death with a bread knife. Afterward, he appeared completely unbothered by the murder. He went about his business as usual, which in his case meant showing up to an appearance in Children’s Court to plead not guilty to a robbery. When he got home from that he found the police waiting to question him about the murder. Upon his arrest, he supposedly told the police “I always wanted to see how it would feel to stick a knife through human bone.” When relating his account of the murder to Yablonsky, he only got agitated at the part of the story where the cops arresting him intentionally dirtied his suit.

Yablonsky thinks the leader of a gang is often the one who is simultaneously most violent and most delusional. These are not young men of great interpersonal or organizational skill, and such charisma as they have operates only in the narrow confines of a fighting gang:

Contrary to the many widely held misconceptions that these leaders could become “captains of industry if only their energies were redirected,” the gang leader appears as a socially ineffectual youth incapable of transferring his leadership ability and functioning to more demanding social groups. The low-level expectations of violent gang, with its minimal social requirements, is appropriate for the leader’s ability . . . he could only be a leader of a violent gang.

He sees evidence for this in gang leaders tending to substantially older than the rank-and-file membership: “A twenty- or twenty-five-year-old youths in a fantasy world of power and violence would appear to have problems.”

These 20-something gang leaders — gang “professionals” — are boys who failed to grow up and move on. They’re less Peter Pan than Gary King. And without their fantasy empire, they become about as pathetic: “Loco and Duke, after the demise of the Kings and Balkans, bore some resemblance to Coleridge’s ‘Ancient Mariner,’ mumbling stories about evens and conditions no longer appropriate or relevant.”

The Production of Sociopathy

Yablonsky sees “sociopathic” disregard for other people as characteristic of both core gang members and the larger social milieu that produces them. It shows up in the tendency to steal and vandalize just for fun. It shows up in the lack of remorse most express even for serious violence. And it shows up in how gang members approach sex: Snoop Dogg’s line “we don’t love them hoes” fits in as well with these 50s gangs as it does with 90s gangsta rap. For gang members, girls and women are objects to be used, sometimes in “gangbangs” in which boys line up for serial sex with the same girl.

Yablonsky thinks all this is learned. His theory of the gang is at root a learning theory, explaining behavior with a socialization process. The explanation in a nutshell is that bad neighborhoods produce improperly socialized kids: Impulsive sociopaths who can’t function in respectable society and use the gang as a vehicle to express their impulses.

I find the theory less impressive than the descriptive material.

One reason is that socialization theories in general need to be taken with a grain of salt, given the evidence that behavioral traits are substantially genetically heritable. You could point José’s father being an abusive alcoholic and say that the abuse pushed José into being a psychopath — but the pattern is also compatible with the alternative theory that he got 50 percent of his DNA from a violent man with poor self-control.

Yablonsky doesn’t dwell on it, but in the opening chapter he also notes that José’s mother was coldly nonchalant to the news that her son murdered another boy. Even the other gang members were shocked when she dismissed the killing with a shrug. Here again, maybe she taught José to be a psycho — but he got 50 percent of his DNA from her as well. And we don’t need to invoke neighborhood and community to recognize that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

Distance and Deviance

Still, we might ask if a different neighborhood or community might not have better restrained José from violence, or his father from drinking, or his parents from fighting. Yablonsky talks a lot about the absence of informal social controls and restraints that might be found in a more peaceable community, including José’s hometown back in Puerto Rico.

The attempt to formalize this with propositions is undercut by concepts that are more judgment than measurement. Socialization is “inadequate,” institutions are “dysfunctional,” communities are full of “human decay and barrenness.” It often seems a lot of verbiage to say, “bad neighborhoods make bad kids.”

But the discussion does focus on a few objective features of the “disorganized” neighborhood. One is that they’re places of high social atomization, high social distance, and correspondingly low generalized trust.

In such neighborhoods, there is “a vacuum of law-abiding youths or adults from whom [a gang boy] could learn any social feelings toward another person.” Thus they learn to treat people as objects to be manipulated and see everything as a “‘con’ game.”

He views the lack of community cohesion and social trust as a major difference between modern slums and traditional slums. But he notes there was still much crime, addiction, and violence in traditional slums, so I’m not sure how far that gets us in explaining gang violence.

If anything, it might explain why the violence of Yablonsky’s gangs was relatively mild! Short-lived groups with fluid membership, his gangs generated weaker partisanship toward insiders and less extreme moralism toward outsiders. Compare the easy-come, easy-go nature of the Balkans the quasi-religious commitment some Los Angeles gangbangers have to their set (see Mark Cooney’s chapter “Configurations of War and Peace” in his book Warriors and Peacemakers).

Another factor Yablonsky returns to is the growing social distance between youth and adults. He thinks in the disorganized slums this is encouraged rapid rural-to-urban migration. The change in environment disrupts patterns of social control and socialization, creating a gap in cultural transmission that deprives youth of any effective traditions or informal authority figures.

The contemporary reader might be surprised by how big a deal Yablonsky makes of youth having a distinctive culture. But while such generation gaps were not new in the 1950s, we ought to keep in mind they’re far from being a human universal. If anything, it’s odd that we take for granted that there will be substantial cultural distance between parents and children. And it seems like Yablonsky and several others of his generation were caught off guard by just how distinctive the postwar youth culture had become. He quotes a reporter who covered a murder trial involving the Egyptian Kings:

There was a sudden shock of recognition of how exactly alike these children are. Vincent Pardon was like every other ward of the Children’s Court we have seen over the last seven days. He had, as an instance, the same hair. . . . These children even talk the same way. . . It is a voice without reference to ethnic origin. . . It makes no difference whether their parents be Irish or Spanish; they do not talk like their parents. It is as though they did not learn to talk from parent or teacher, but from other children . . .

Yablonsky also emphasizes the relational distance — the lack of intimacy — between the gang boys and their elders: “A typical Egyptian King response to the question of how he gets along with his parents is: ‘Why should I talk to them? There’s nothing to talk about.’” Another, after describing a poor relationship with his divorced mother, says of his father, “Who, him? I never see him anymore.”

The resulting lack of social integration and informal social control could indeed encourage violent and delinquent behavior. But as Donald Black long ago observed, the same factors proposed to explain deviant conduct itself also help explain the defining of deviance. Social distance and absence of informal authority would have made youth attractive to law, and perhaps to other outside social control.

The early 1950s saw something of a moral panic about youth violence and juvenile delinquency. As you nerds know, one side effect was the demonization of comic books, the creation of the Comics Code Authority, and the death of EC Comics. The growing social distance of the youth — an increase in the size of the generation gap, a separation of the adult and youth spheres — could explain fear of youth gangs as much as it explains the gangs themselves.

Thanks again! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole, please leave a tip at this Stripe link or become a subscriber with the button below.