Wherever you’re reading this, I appreciate your interest! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole you can become a free or paid subscriber with the button below. Or if you’re not the type to commit, you can leave a tip at this Stripe link.

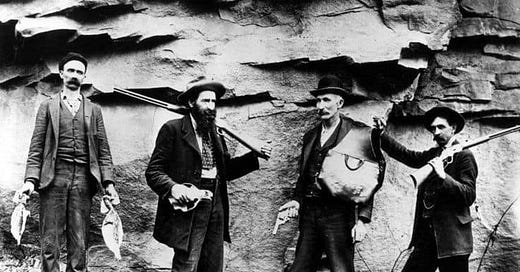

Sociologist Donald Black defines the classic blood feud as “a precise, extended, and open exchange of killings, usual…