Books: Days of Rage

America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence.

Thanks for your interest! If you’d like to support Bullfish Hole you can leave a tip at this Stripe link (you can change the default amount to anything) or with Paypal. You can also become a free or paid subscriber at the link below.

Note: I was first turned onto this book by David Hine’s insightful review. Since that already exists, I’ll try not to retread his points.

Bryan Burrough’s Days of Rage details the waves of revolutionary violence in 1970s America. It was an age of radical groups declaring war on the US government, of bombings and assassinations, of kidnappings and bank robberies. And it’s an age that is largely forgotten, despite its strange and dramatic events. He opens his book by asking us to consider how we would react to such things in our time:

“Imagine if this happened today. Hundreds of young Americans…disappear from their everyday lives and secretly form urban guerilla groups…they strike inside the Pentagon, inside the U.S. Capitol, at a courthouse in Boston, at dozens of multinational corporations, at a Wall Street restaurant packed with lunchtime diners.”

In my pitch for a new honors course at WVU, I said that Americans have collective amnesia about collective violence. True, a few incidents — like the killing of Emmett Till — gain notoriety as popular symbols of injustice. But scores of deadly riots, terrorist bombings, violent rebellions, and bloody clashes are only remembered by history nerds — sometimes mostly by local history nerds. Burrough, in going over the forgotten age of 70s radical violence, hints at previous forgotten ages, like anarchist bombings of the early 20th century.

Even major wars can quickly fade from public consciousness — there’s a reason Americans call the Korean campaign the “Forgotten War.” Smaller scale violence just drops down the memory hole completely. This is especially so if the violence is somewhat embarrassing for participants who are connected to prestigious institutions, as is the case for much of the radical violence of the 1970s.

The Movement Goes Radical

The revolutionary violence of the 70s grew out of the protest movements of the 60s.

The US Civil Rights movement picked up steam through the 1950s and continued into the 1960s. By the mid-60s American involvement in Vietnam spawned a growing anti-war movement. The second wave of feminism was also up and running. College students were discovering marijuana and fascinated by Marx.

Many people then and now see all the currents of protest, activism, and rebellion coming together in the late 1960s as one larger political force — The Movement. It was against all that was Old and Bad — capitalism, patriarchy, militarism, colonialism, and most of all racism. There was a sense of common cause that carried over into the 70s radicalism, where despite factional conflicts there was also cooperation and even circulation of personnel among different radical groups, as well as an extensive network of underground and aboveground supporters.

So why did many in The Movement turn radical? How do we get from the peaceful marches of Martin Luther King to urban guerillas assassinating cops and planting bombs?

Burrough says part of the impetus for escalation was the perceived failing of The Movement. People thought that either they weren’t achieving change, or that they were being pushed back and defeated. This was what led activist Sam Melville to contemplate bombing:

“The Movement—the great swelling of young Americans that had thronged the streets in protest over the past three years—was crumbling. Everyone sensed it. A new president, Richard Nixon, was entering the White House, pledging to crack down on student radicals. What that meant had become clear at the Democratic National Convention in August, when Chicago police used truncheons to beat down demonstrators, leaving them bloodied, bowed, and defeated.

….Many were giving up hope. But others, Melville included, began talking about fighting back, about genuine revolution, about guns, about bombs, about guerilla warfare.”

This argument is similar to sociologist James Davies’ theory of revolution. Davies argues that poverty, misery, and oppression were the norm for the history of most civilizations, and so chronic levels of these are not sufficient to explain why people rebel. And contra Karl Marx, people do not revolt due to a steady process of immiseration. If things get steadily worse, people become steadily adapted to it. You can boil the frog without it jumping.

No, Davies said, people rebel when things have been getting better for a while — and then there’s a reversal. “Better” can be measured by wealth or freedom or progress toward a political goal. Either way, improvements in these conditions cause higher expectations, and the sudden reversal frustrates these expectations — even if the reversal leaves everyone better off than they were five or ten or twenty years prior, before the period of improvement began.

Political scientist Abraham Miller and colleagues applied his theory to the black riots of the 1960s and came away unconvinced. They measured black economic success with the gap in earning between whites and blacks in the same region with the same education level. They argue that there were swings up and down throughout the 1960s, rather the prolonged improvement and sharp downturn that Davies expected. You can judge their line-graph for yourself. Personallly, I think it looks like Northern blacks had a choppy upward trend followed by a steep decline.

Keep in mind there were riots in in almost every year in different cities, but the biggest waves were in 1967 and 1968 (with the 1968 wave sparked by the assassination of Martin Luther King). Given that different places had riots at different times, I’d be curious what a city-by-city analysis would show.

In any case, it does seem to me that however bad things were in 1968, black Americans certainly weren’t any more oppressed in 1968 than in 1958 or 1948 or 1938. The Civil Rights movement had won victories throughout the 50s and 60s. But many radicals were convinced that things were on the downslope. Burrough quotes one as saying that the Civil Rights Movement had “gone wrong” and that his contemporaries were convinced America was becoming another “Nazi Germany.”

That grievance is delusional exaggeration but likely reflects real setbacks like the assassination of Dr. King, continued violence toward black activists, and continued clashes between urban blacks and police.

The Underground

These groups were situated in a broader ecosystem, an outgrowth of The Movement called The Underground.

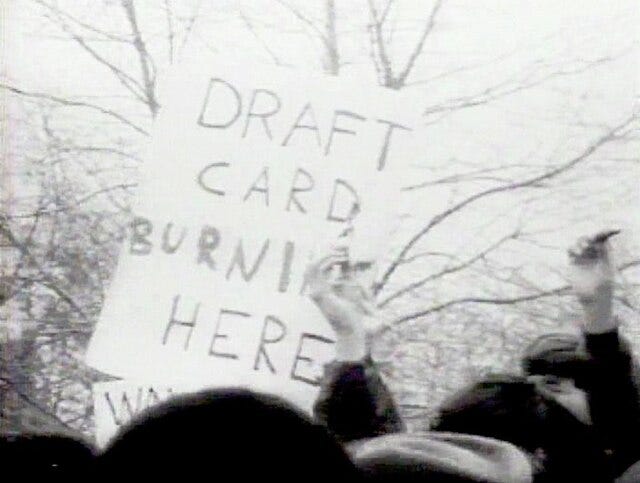

“Being underground” mostly meant being a fugitive living under an assumed identity. While most radicals weren’t fighting against the Vietnam War, the war did help create the social environment in which they thrived. This is because it led to hordes of young men becoming fugitives to avoid serving:

“The Pentagon listed 73,121 deserters in 1969, 89,088 more in 1970. Many turned themselves in, were arrested, or fled to Canada. But draft resistance groups estimated that between 35,000 and 50,000 deserters were living underground in the United States in 1970. The FBI’s central computer listed 75,000 additional criminal fugitives.”

Thanks to the thousands of draft dodgers and deserters, there was a huge demand for fake identities, which naturally led to suppliers. Thus emerged a network of those who could help one find or forge documents, as well those willing to shelter and assist various brands of fugitive from the law. The network included those who were themselves underground as well as “aboveground” sympathizers — some of them, such as radical attorneys, quite well placed to shape the behavior of legitimate institutions.

Indeed, a point that David Hines really emphasizes in his review of the book is the role of such institutions in allowing violent radicals to get away with it. This support prolonged and exacerbed their activities, and also ensured that the well-connected radicals got treated with kid gloves when caught.

Well-connected generally meant well-educated and was much more common among the white radicals than the black ones. The Black Liberation Army mostly wind up dead or in prison, while the lily white Weathermen wind up with faculty positions. Angela Davis is the exception that proves the rule, being a highly educated black radical who came out fine and still gets treated like royalty in the academy.

It’s all connections: some connections get you a fake ID, some connections teach you how to make bombs, some connections get you out of jail, some connections get you a job.

I’d like to see a serious network analyst go to town on this subject.

Bomber Zero

Not all of the radical groups were bombers — some mostly shot people — but bombing was common in this period. So common it rarely made headlines — bombs going off were just part of the background of life. Part of the reason the public was so blasé about bombing in the 1970s is that the large majority of these bombings didn’t kill anyone. Most were meant only to destroy property and garner attention. Still, the scale of the practice is shocking: There were over 1,900 domestic bombings in 1972 alone.

What sparked the rise in bombing?

The thing about people is that while we’re collectively innovative, most individuals never innovate at all. So every now and again you’ll see some tactic or technique suddenly become common, seemingly because one person had the idea to do it and others followed.

For instance, protest suicides have happened off and on throughout history, but it wasn’t until the highly publicized self-burning of a Vietnamese monk in 1963 that it became a regular part of the protest repertoire. Sociologists Michael Biggs argues that almost all all political self-immolation since were directly or indirectly inspired by that example.

Likewise, bombing campaigns have been going on in various times in places for a century or more, but Burrough traces the 1970s era of bombings in the US to one man, his “patient zero”: Sam Melville.

Melville was 35 in 1969, making him five or ten years older than most of the radicals who would follow in his footsteps. He found a cause in anti-war activism and became a passionate part of the protest movement. In 1968 he began talking about bombings.

Though he is Burrough’s patient zero, Melville wasn’t so innovative either. He got the idea for a bombing campaign from another forgotten bit of American violence: A disgruntled electrician who planted dozens of bombs around New York in the 1940s and 1950s. And the idea might have remained idle fantasy if a friend of a friend hadn’t put him into contact with two experienced terrorists who taught him to make bombs.

The terrorists in question were Canadian — no, not the Trailer Park Boys, but two members of a group that had killed at least eight people over the years in its campaign for an independent Quebec. They needed to lay low for a while and so in exchange for hiding in his apartment they taught Melville about making and planting bombs. They eventually left and hijacked a plane to Cuba — a success that further inspired and emboldened Melville.

So, it’s 1969 and you want to make a bomb. Where do you get explosives?

Melville looked up “explosives” in the Yellow Pages.

Having located a distributor, he recruited some radical friends to pull off an armed robbery at the distributor’s warehouse. He was actually doing it the hard way, since some other radicals would just buy their dynamite at the hardware store, or swipe dynamite from unguarded construction sites. At the dawn of the 70s getting dynamite was easy. The past is a foreign country, and in this case it’s a country with much looser security.

It reminds me how in the year 2000 I went to the airport carrying a boxcutter from my grocery store job and walked right down to the gate and meet a friend as he stepped off the plane. The 1970s radicals helped usher in tighter control of explosives just like they led to tighter security at government offices and big businesses, just like the Salafi jihadists gave us long security lines and taking off our shoes.

With his newfound dynamite Melville and co. set about bombing. The first target was a factory they believe, incorrectly, was owned by United Fruit, a favorite enemy of Latin American communists. Then came a Wall Street bank, a bomb in the NYC Federal Building intended for the Army Department but that actually blew up at the Department of Commerce, a draft induction center, Chase Manhattan Bank, the General Motors Building, the Standard Oil office in the RCA building, and the New York City Criminal Court.

Notably, one of these bombings had a very mundane proximate cause. Melville and his girlfriend had a fight and agreed to see other people. On the night she had a date with another man he went, alone, to plant the bomb at the Wall Street Bank. His girlfriend went along with the other bombings but was critical of this one, both because he gave little thought to the potential casualties at a building where many worked late into the night, and because:

“The bombing, she saw, had nothing to do with the war or Nixon or racism…she knew it was about her. As she wrote years later, ‘Because I had threatened to abandon him, for even one night, by sleeping with another man, he had taken revenge on a skyscraper full of people.”

The incident is a reminder that people don’t always take out their grievances on the target of the grievance — sometimes liability is displaced onto others, including traditional enemies or other acceptable targets.

Maybe the targeting of Chase was also a mix of the personal and political. Melville used to have a family, but his marriage had foundered after he quit his job as a draftsman, and the reason he quit was in outrage over finding out that his company had been hired by Chase Bank for a building project in apartheid South Africa.

Melville was soon busted by the FBI and would die a couple years later in the Attica Uprising. His girlfriend made bail and went underground. But in the meantime they were hailed as heroes in activist circles, cheered at a public rally, and their arrest triggered a massive wave of bomb threats throughout New York.

Dramatis Collectivae

Burrough goes on to trace the history of the era, focusing on the most consequential radical groups. Of these, the Black Liberation Army, Weatherman, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Puerto Rican separatist group FALN get the most attention. I’ll focus on these here, with a little attention to spare for the bizarre cadre known as the Family.

A quick summary of each:

Black Liberation Army (BLA): Black Panthers gone wrong. They tend to have criminal histories and radicalize in prison. Very loosely organized, but they’re comfortable with and moderately competent at violence, so deadly. They hunt and kill policemen with shooting ambushes. They fund themselves with robberies. Most wind up in prison or dead in shootouts with the cops.

Weatherman: White liberal arts majors gone wrong. They’re well-off wordcels who form a Marxist cult with orgies. Fairly well-organized but largely ineffective. They initially aim to kill cops and soldiers but turn out not to be so comfortable with or competent at violence. Their bombs are mostly nonlethal, except for blowing up themselves. They are funded by radical lawyers and rich friends. They tend to come out fine and get sweet academic jobs.

Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA): Dysfunctional Berkely activists following a crazy black convict with delusions of grandeur. More like a small cult, they’re most famous for kidnapping and recruiting an heiress. They also kill a couple people, rob some banks, and plant a few bombs. Half of them burn to death in a police siege, the other half are rolled up by the FBI.

Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional (FALN): Hardcore Puerto Rican separatists. Trained by experienced Cuban revolutionaries, they’re easily the most competent of the bunch. They set off hundreds of bombs, kill several people and wound many others, and manage to evade the FBI for a long time thanks to discipline and support from the Episcopal Church. Mostly wound up in prison but got pardons before their sentences were up. Their leader was celebrated on Broadway by the creator of Hamilton.

The Family: Male BLA survivors hook up with female Weatherman remnants and break a FALN bombmaker, among others, out of prison. In between robberies they’re basically funded by the state of New York, as they had drug treatment and acupuncture clinics that they used to fuel their revolution and cocaine habit. Killed security guards and police. Most went to prison, one became a professor, and one was rapper Tupac Shakur’s step-dad.

As you might be able to tell from these examples, for North Americans the two big pipelines into radical groups were college (mostly for the whites) and prison (mostly for the blacks). The Puerto Ricans played their cards more closely to the chest, or maybe the English-language sources are thin. But their leader started out as a Chicago community activist who went Communist.

None of these groups gave much attention to the Vietnam War. These were not hippie peaceniks, but hard-left revolutionaries. They liked Castro and Mao.

Aside from the Puerto Ricans, all these groups were mainly concerned with black America. Even the hardcore Marxists, despite being ideologically committed to a broader revolution of the working class, tended to focus on the black cause — and caught hell from the other radical groups if they ever strayed from it. All the white radicals wanted the approval of the black radicals, and generally they seemed to idolize them. Some female radical attorneys had schoolgirl crushes on their favorite radical black prisoners, just like girls in the 60s having their favorite Beetle. When Weatherman fell from grace in radical circles, they were denounced as racists.

Yeah, I know. People on the bleeding edge of the far left denouncing each other as racists. Those crazy 70s.

Let’s consider these groups in more detail, beginning with the BLA. Only the story of the BLA starts with the Black Panthers, and the story of the Black Panthers starts with the Civil Rights Movement.

From Self-Defense to Insurrection

While everyone remembers Dr. King’s tactics of non-violent protest, there was another, less prominent side to the movement: “self-defense.” As the Civil Rights movement gained steam in the 1950s many black Southerners armed and organized to protect themselves and their peacefully marching brethren.

For instance, in 1955 Robert Williams, a chapter head for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), responded to Ku Klux Klan violence in North Carolina by founding the Black Armed Guard — mostly NAACP men who started carrying guns. He gave interviews threatening that if the Klan attacked a black man in the town there would be retaliation. But an alarmed NAACP suspended him and after some legal trouble he fled to Cuba.

More influential in spreading the idea of self-defense was Malcom X. From a Northern slum, he engaged little with the Southern Civil Rights Movement and instead focused on police brutality. Arrested for burglary when young, he — like so many after — radicalized behind bars, joining a tiny sect known as the Nation of Islam.

After prison, he was put in charge of a mosque in Harlem and gained a following as a writer and speaker. His charisma outshined the sect’s official leader and attracted many new members. In 1957, following the police beating of a black man, Malcom dispersed a crowd that seemed on the verge of rioting with just a quiet word. This supposedly led one policeman to mutter “That is too much power for one man to have.”

Malcolm was enthusiastic about black self-defense and turned a lot of young black men onto it. But Malcolm soon had a falling out with Nation of Islam’s leader Elijah Muhammad, and wound up assassinated by black Muslims.

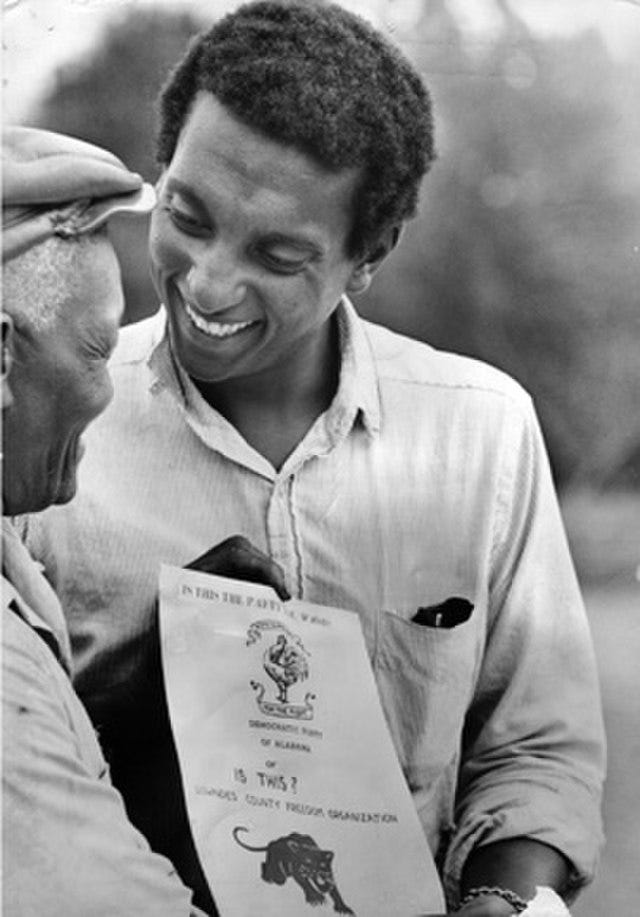

The torch of black militancy passed to Bronx born, Howard University graduate Stokely Carmichael. He joined an organization, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, that started out registering black voters in the South. But the angry young men in the group grew impatient with the stoic tactics of Martin Luther King. They opted for something more assertive.

They picked an Alabama county that had been especially repressive to civil rights organizers and formed a new political party there with the explicit goal of taking power. Their symbol was a black panther. They failed to win offices, but they put themselves and their symbol on the map. Soon dozens of black activist groups would call themselves “Black Panthers,” though only one would be truly famous.

Carmichael led a more militant faction of the Civil Rights protestors — during one protest event, while Dr. King’s followers sang “We Shall Overcome,” Carmichael’s supporters sang “We Shall Overrun.” When he was arrested in Mississippi in 1966, he and his followers chanted “black power!” The term quickly became popular.

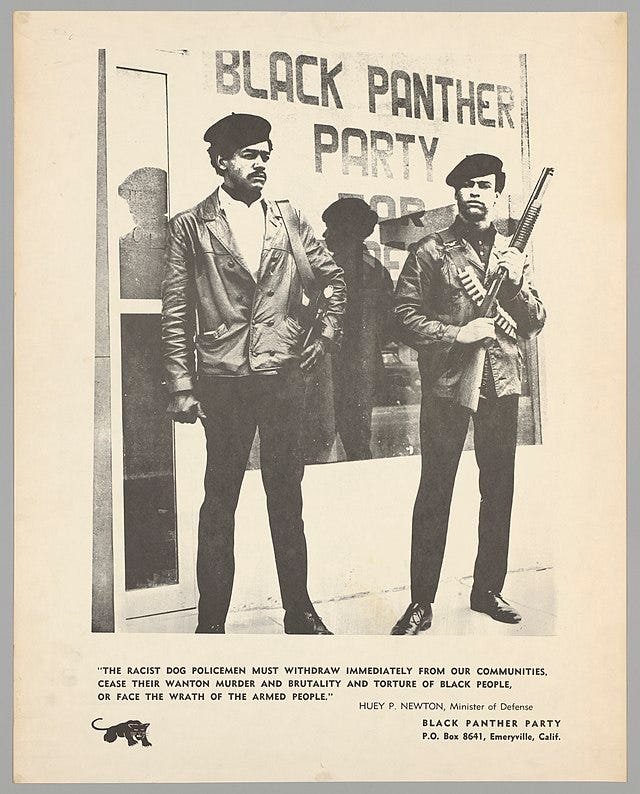

Soon after, in Oakland two young friends Huey Newton and Bobby Seal headed the call for black power and adopted the black panther symbol. They formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. The idea was for the group to patrol black neighborhoods to monitor the police for brutality. Their message to police was “kill a black man…and retribution will follow.”

It started out as just the two of them and a few friends. They learned to use and clean their weapons and began regular patrols. When they came across a black citizen being questioned by police, they would exit their car with drawn guns and remind the citizen of his rights, responding to questions or demands from the officer by reminding him of their right to bear arms.

Their message and image was popular with young black men. And Newton had a talent for theatrics, including the signature panther costume: brown leather jackets and black berets.

One publicity-generating incident happened when Newton himself was stopped. He politely answered questions, but he and Seale kept their guns in plain sight. Other officers arrived and one demanded to see the guns. Newton refused and told him to get away from their car. When the officer reprimanded him, he stepped out and chambered a round into his M1 rifle. The officer asked him what he would do with the gun, Newton turned the question on him, and added that “if you shoot at me or if you try to take this gun, I’m going to shoot back at you, swine.”

Other armed confrontations with the law likewise generated publicity, and image of strong and fearless black men standing up to the cops was attractive. The Black Panthers rapidly grew to a national organization.

One new recruit was serial rapist Eldridge Cleaver. Sentenced for rape in 1965, he too joined the Nation of Islam in prison. He also discovered a talent for writing. He seduced radical San Francisco Bay Area attorney Beverly Axelrod, who helped him secure him an early release and a gig writing at a radical magazine. She later admitted she’d gotten played. Cleaver soon joined the Black Panthers, and went on to write a popular memoir Soul on Ice.

In it, he describes his serial rape of white women as a revolutionary act, punishing the white man by defiling his women just as the white man had previously defiled black women. As for his serial rape of black women — well, he had to practice first.

The man was brutal. But his writing skill gained him a following — especially among white radicals, who would come to deify black prison inmates like Cleaver. And it led to him rising in the ranks of the Black Panthers. This would be consequential.

As one might expect, the law hated the Black Panthers. The FBI started bugging their headquarters early on, and Huey Newton claims to have been stopped by the cops over fifty times. But the Panthers under Newton, while aggressive and confrontational, weren’t so violent. Newton was no angel — he had a stabbing conviction and would soon do time for a manslaughter — but he mostly used the tough image and language of self-defense as a recruiting tool. It was to appeal to young men full of piss and vinegar and desire to do something hardcore. But recruits actually wound up doing community service projects — the goal was more to keep them off of drugs and out of white institutions, like prison and school, than to fight a bloody conflict.

Cleaver, on the other hand, just really wanted to kill cops. And when Newton was arrested in 1967 after a traffic stop devolved into a shootout, Cleaver assumed leadership of the Panthers.

Cleaver quickly began advocating violent insurrection.

“It was the Panther newspaper, the Black Panther, that coined the phrase “Off the Pig;” Under Cleaver, the Panther openly called for the murder of policemen, supplying tips on ambush tactics and ways to build bombs.”

One Panther was arrested for boasting that the group would kill President Nixon, while Cleaver himself spoke of burning the White House down. This sort of thing only escalated their conflict with the law.

Soon Cleaver decided to turn words into action by going out with some fellow Panthers on a mission to kill cops. Only the mission went sideways when, before they could set up their ambush, a cop car rolled up behind theirs. The Panthers came out shooting but were scattered. Cleaver and his comrade Bobby Hutton took cover in a nearby residential basement, where they had a 90-minute gunfight with police. When they finally surrendered, the police beat Hutton and, when he stumbled, shot him to death.

Killing a Panther in custody sparked outrage, and in 1968 the assassination of Martin Luther King sparked more, including a fresh series of riots. Angry black men flocked to the Black Panthers, and local chapters sprang up around the country.

But even as their numbers swelled, the Black Panther organization weakened. Newton was behind bars. Cleaver got out on bail and fled the country. The new chapters had little in the way of strong leadership.

The West Coast Panthers tried to maintain some authority over their brethren on the East Coast, but the two groups diverged culturally. The East Coast Panthers got more into Afro-Centrism, wearing dashikis and taking African names.

A rift between the two started in 1969 when a group of 23 New York Panthers planned a series of bombing and shooting attacks on the police. Only two of their number were police informants, and the other 21 were arrested and tried on conspiracy charges.

The case of the “Panther 21” became a cause célèbre for activists — one of Sam Melville’s bombing targets was the courthouse where they were being tried. The East Coast Panthers complained mightily that the West Coast organization wasn’t doing enough to support them. And when a delegation of West Coast Panthers visited New York, the New York Panthers complained of open disrespect — these guys were hitting on their girls, making fun of their clothes, and spending the last of the petty cash.

The next phase of the rupture occurred in 1970 when both Newton and Cleaver came back on the scene. Newton’s case too became a cause célèbre, which might be why he only served two years for killing a cop. Free again, he tried to reassert some leadership over the Panthers. The problem was the organization had grown drastically, and its rhetoric had gotten more violent even as his stint in prison had convinced him of the need to tone it down.

Cleaver, on the other hand, had managed to set himself up in Algeria, where he claimed to be running the Black Panthers International Chapter. He even convinced the newly independent government to set him up with an honest-to-God embassy. He was bona fide.

Newton and Cleaver had a televised phone conversation that quickly became a heated argument and ended with each expelling the other from the party. The West Coast Panthers broke for Newton, and the East Coast Panthers broke for Cleaver. Begun, the Panther civil war had.

I’m afraid this discussion is growing rather long, as I don’t have time to write a shorter one. So this will have to be a two-parter. Read Part 2 to find out how the BLA was born, and to learn more about the other radical groups!

Thanks for reading! If you liked it, subscribe or leave a tip.